Time to Debunk a Myth From Radio’s Infancy:

Aimee Semple McPherson’s Telegram

to Herbert Hoover

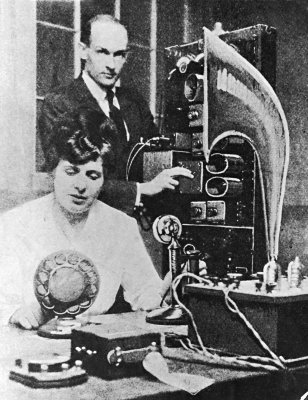

1927 photo

1927 photo

Copyright 2011

By JIM HILLIKER

Is it true that Los Angeles evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson sent an

angry telegram to Secretary of

Commerce Herbert Hoover about her radio station at Angelus Temple,

KFSG? The supposed 1920s era telegram reportedly contained the

phrase “please order

your minions of Satan to leave my radio station alone!” In 2003 I

wrote an

extensive history of the now-defunct station, KFSG. I felt the

telegram story

was true. Now in 2011, after closely examining all of the

facts, I believe

this is another myth from the earliest years of broadcasting, such as

KDKA in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania being the first radio station in the

world.

More than 85 years have

passed since McPherson put 500-watt KFSG on the air at 1080 kilocycles on the

AM radio dial in 1924. It may be difficult to convince people today that this

legend of radio history never took place. I have set out to find evidence to,

if not set the record straight, then at least present enough evidence to show

that the incident likely never took place.

My earlier history of KFSG

written eight years ago, initially showed that the archives at the

International Church of the Foursquare Gospel headquarters concerning

KFSG were simply not

accurate. By providing them the correct information, they know now that

KFSG

was not the third station on the air in Los Angeles and was not the

first

Christian station in the nation. But it was, however,

unquestionably an

important pioneer in religious broadcasting, remaining on the air for 79

years

under two AM licenses, and then on the FM band after 1970. Also,

while

McPherson was not the first woman to own a radio station, she was the

second

woman to do so, and one of only six female radio station owners during

her

lifetime.(Halper 68-69)

HOW AN EARLY RADIO LEGEND SPREAD

Since the 1950s and 1960s,

more than 50 books on radio history including college textbooks on the subject,

books about religious radio and the memoirs of former President Herbert Hoover

have mentioned the telegram story, without questioning the accuracy of the

story. (Search of Google Books) But oddly all of the books on the life of

Aimee Semple McPherson made no mention of the Hoover telegram story, except for

one, which was published in the past decade.

After the story was

originally published in Hoover’s memoirs in 1952, the famous broadcast

historian Erik Barnouw accepted the “minions of Satan” telegram as factual in

his 1966 book, A Tower In Babel—A History of Broadcasting In the United

States to 1933 (Barnouw 180). Barnouw quoted the “minions of Satan” story

again in a 1982 journal article. (Barnouw 13-23)

Apparently all of the other

books which repeated the McPherson-Hoover telegram story obtained their “facts”

from either Hoover’s memoirs or Barnouw’s book. One book on the topic of early

Pentecostals, while not a biography of McPherson, also quoted the “minions of

Satan” telegram, citing the Barnouw 1966 book and a 1987 book by George H.

Douglas on the early days of radio broadcasting. (Wacker 33). A 2007 book by

Matthew Sutton titled Aimee Semple McPherson and the Resurrection of Christian

America is the only biography of her that has mentioned the story of the

telegram. (Sutton 81-82)

According to Matthew T.

Schaefer, who in 2003 was the Archivist for the Hoover Presidential

Library in Iowa, trying to separate the legend from the history of the

McPherson telegram is

difficult. On the other hand, Schaefer said that given Hoover’s

careful

attention to documenting history, he is inclined to believe the story is

true.

(M. T. Schaefer, personal communication, April 7, 2003) But

even the Hoover

Presidential Library website has errors concerning portions of the story

regarding KFSG. I’ll have more to say about that later.

But, if this incident

happened in the 1920s, why is there no record of it in the popular media of the

day? In searching the historical archive of the Los Angeles Times and

the New York Times, I’ve been unable to find any stories or

reports

about any dispute between McPherson and Herbert Hoover. In

addition, I could

not find a single story in newspapers or radio magazines of the 1920s

reporting

that KFSG had been taken off the air by the government or had lost its

license,

as Hoover claimed. According to the records of the Department of

Commerce, no

such action against KFSG ever took place. (Radio Service Bulletins

February

1924 to December 1927). And, there were no newspaper stories or

radio magazine

articles reporting that KFSG had wandered off its assigned frequency or

used

too much power in 1924, ‘25, ‘26 or ‘27. Those are the years that

the various

books have listed for the time of the alleged telegram sent by McPherson

to Hoover, though no specific date has ever been given for this alleged

incident.

STATION BACKGROUND

KFSG had its very first

broadcast on the evening of February 6, 1924. It was the 12th

radio station to go on the air in Los Angeles with a regular broadcast

schedule. However, by this time, a few of the stations that

began operating

in 1921 and 1922 had gone out of business and were off the air by

1924. Only

KNX, KHJ, KFI, and KJS (later known as KTBI, KFAC and now KWKW-1330)

were on

the air regularly. In another 4 weeks, a new Long Beach radio

station, KFON

(later KFOX and now KFRN-1280) would also be on the air regularly.

A bit later

in 1924, KFPG (now KLAC-570) and KFQZ were licensed, but were

broadcasting with

irregular schedules. Also, KPPC in Pasadena went on the air in

Pasadena at the end of 1924 and in March of 1925, KFWB in Hollywood

began broadcasting.

The Los Angeles area radio dial was gradually becoming more

crowded. (Radio

Service Bulletins, February 1924 to December 1925)

In January of 1924, roughly

10.8 percent of the homes in the United States owned a radio set. By January of

1925, that figure had increased to 14.4 percent and by January of 1926, to 18

percent. The number increased to 23.3 percent of U.S. homes with a radio in

January of 1927 and 26.9 percent in January of 1928. (Douglas xx-xxi)

When KFSG first went on the

air in 1924, radio broadcasting was still in the early stages of development,

as were the various types of radio sets the public used to hear the radio

broadcasts. Most radios at that time were fairly expensive and not very

simple to operate. Also, there was not one standard way of tuning for stations

on mid-1920s radios yet, as we have today. There were several types of radios

on the market, including the crystal set, the TRF or tuned radio frequency

receiver (also called the neutrodyne), the regenerative receiver and the

superheterodyne receiver. Improvement in vacuum tube technology and a demand

for cheaper, higher-performance radios caused the superheterodyne to become the

way most radios in the United States were designed by the 1930s.

Before the Federal Radio

Commission was formed by an act of Congress in 1927, broadcasting was regulated

by the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Navigation, Radio Division,

under the Radio Act of 1912. The 1912 radio law mainly covered wireless code

between ships and ship-to-shore wireless code, along with amateur radio. It

did not specify how broadcasting stations should be regulated. Secretary of

Commerce Herbert Hoover was the man in charge of radio broadcasting at the

time.

1927 photo

1927 photo

THE ONLY PROOF KFSG WAS WARNED ABOUT INTERFERENCE

KFSG had been on the air for

only 2 weeks, when it received an important letter from the 6th District

Radio

Inspector, Col. J.F. Dillon. Dillon had been one of the guest

speakers on

KFSG’s first broadcast on February 6 and Aimee had met him on previous

occasions. His district covered not only California, but also

Arizona, Nevada, Utah and Hawaii. A photocopy of this and a second

letter to Aimee Semple

McPherson at KFSG-Angelus Temple were sent to me by the National

Archives, as

part of a KFSG license file from the 1920s and ’30s.

In the first letter dated

February 21, 1924, Dillon writes, “This office is daily receiving complaints

regarding interference caused by the operation of KFSG, with the reception from

KFI, KHJ and distant stations.” Dillon says that with KFSG on the air every

day and night, he would have no choice but to order the station to share time

on 278 meters/1080 kilocycles with other religious groups in the Los Angeles

area. Dillon stated in the letter that other religious organizations were also

seeking a broadcast license. Dillon suggested that KFSG go on the air only 3

nights a week, to allow better reception to those whose radio reception was

being ruined by KFSG’s strong signal. (KFSG license file, National

Archives)

In an email, radio historian

Thomas H. White said that 278 meters (1080 kilocycles/kilohertz) was one of the

frequencies opened up when the broadcast band was expanded on May 23, 1923 to

include 550-1350 kilocycles. White noted that KFSG should have had unlimited

use of this frequency as it saw fit. (T. H. White, personal communication,

November 27, 2011)

The second letter from Dillon

was sent to McPherson on February 28, and mentions her letter of the 26th,

but no copy of that letter has ever been located. Again, Dillon tells

McPherson that complaints about the operation of KFSG continue to arrive at his

office. Dillon felt that if there were more radios made with better

selectivity to block out or filter strong signals from a nearby radio station,

that radio fans that lived close to the KFSG transmitter, would be able to get

better reception of KHJ and KFI. Dillon’s letter is polite, with no warning or

threat of taking away her license or taking KFSG off the air. He instead

suggests once more that KFSG cut back its broadcast schedule from 6 or 7

days/nights a week to three or four days on the air each week. (KFSG license

file National Archives)

The National Archives KFSG

file did not include any other such letters on this topic. I sent email copies

of the letters to radio historian Thomas H. White, who is an expert on the

early regulation of U.S. radio broadcasting. Since 1996, Mr. White has been in

charge of his website on early United States radio history from 1897 to 1927.

White has also written several original articles on early radio history. He

sent me the following comments:

Those letters were

interesting, in showing how individual Radio Inspectors tried to

handle controversies in the days before the formation of the Federal Radio

Commission. I suspect this led to inconsistencies in the various districts,

plus the inspectors probably found themselves on shaky legal grounds trying to

justify their decisions. The interference problems were mostly around the

transmitter sites, and were due to inexpensive receivers with limited

selectivity. (Some stations were accused of having “broad waves”, but

the actual problem was always with the receivers.) (T. H. White, personal

communication, November 17, 2009)

Media historian Donna Halper

also commented on the letters from Dillon:

“I’m not surprised to find

that KFSG might have been asked to limit its time on the air so that other

smaller station or stations with weaker signals might have a turn to broadcast.”

Halper said the AM dial had not been fully opened up yet, and the spectrum was

getting quite crowded with other stations trying to get on the air. She also

noted that religious stations of the days were normally only on the air on

Sundays, or Saturdays for Jewish services. KFSG staying on the air nearly

every night was new to the Commerce Department. Halper said, “A number of

churches owned stations, but the ones I know about limited their time to

Sundays or to religious occasions (like Christmas). They were not on the air

full-time with religion.” (D. Halper, personal communication, November 12,

2009)

Station KJS at the Bible

Institute of Los Angeles was broadcasting mostly religious programs other than

on Sundays. But, KJS was not on the air every day like KFSG, which was

broadcasting 6 out of 7 days a week.

In the book The Beginning

of Broadcast Regulation in the 20th Century, Marvin Bensman

wrote about the various problems the radio inspectors faced between 1922 and

1926. Bensman specifically mentioned an incident which involved Dillon. Dillon

had tried to solve another Los Angeles radio controversy in early 1923, when

KHJ and KFI were required to share time on the Class B frequency of 400 meters

or 750 kilocycles. When the two stations refused to divide air time equally,

Dillon came up with his own plan to avoid interference and broadcast at the

same time. He informed his supervisor in Washington, D.C. that he would have KFI

operate slightly below 750 kilocycles and KHJ would go on the air a bit above

750 kilocycles. But his superiors at Department of Commerce told Dillon this

was unacceptable and had KFI and KHJ go back to sharing time on 400 meters.

(Bensman 75-76)

And in 1922, when all

broadcasting stations were assigned to share air time on 360 meters (833

kilocycles), Dillon was supposed to assign arbitrary time divisions to all

stations in San Francisco and Los Angeles. Instead, he told the radio station

owners it was their problem and not his. Dillon let the radio stations work

out the time-share agreements, and Secretary Hoover highly complimented him on

this method. (Los Angeles Times March 6, 1927)

When KFSG came on the air in

1924, KFI and KHJ had their own frequencies, 640 and 760 kilocycles,

respectively. Their output power was 500 watts, as was KFSG, which was

considered “high power” at that time. KNX at 360 meters/833 kilocycles at 100

watts would boost power to 500 watts by the end of 1924 and move to 890 on the

radio dial. But other Los Angeles area stations operated with 100 watts or

less, which added to the interference problems of the less selective radios. (Radio

Service Bulletins, February to December 1924)

INTERFERENCE A COMMON PROBLEM IN EARLY RADIO

It appears that the radio

stations and the federal Radio Inspectors had their jobs cut out for them

during the early and mid-1920s. J.F. Dillon of the 6th Radio

District in San Francisco also had the problem of finding out if the

interference was caused by the radio station’s transmitter or by the radios

that could not separate the stations properly.

In some cases, stations were

told by potential listeners to stay off the air because they interfered with

other stations they were trying to hear in the same city. This problem of

1920s era radio was pointed out in the 1937 book, Education’s Own Stations

by S. E. Frost. Here are three examples from Chicago and two cities in Michigan:

Furthermore, since the

station was located in the heart of Chicago and was operating with 500 watts

power, it drowned out every other station in the area. As the school drew its

business from amateurs who were interested in hearing every station possible,

the prominence of Station WGES was creating considerable ill-will, and the

venture proved a detriment rather than an asset. (WGES, Coyne Electrical

School, Chicago)

Further, the signals of

the station were such as to interfere constantly with local reception of other

stations in the area. Complaints of this fact were coming to the College

daily. (WOAP, Kalamazoo College, Kalamazoo, Michigan)

Further, numerous

complaints were made locally that whenever the College station was on

the air,

other stations could not be heard in the immediate area.” (WWAO,

Michigan College of Mining and Technology, Houghton, Michigan) (Frost

78, 142, 149)

During the 1920s, radio

stations had their transmitter and broadcasting studios in the same location.

That is often not the case today. Transmitters are usually located many miles

from the studios. In all of the above examples by Frost, transmitters were

apparently strong enough to interfere with reception of other radio stations in

homes with radios located fairly close to where radio station transmitters were

located. This was a fairly typical situation at the time and is also what

happened when KFSG went on the air. The station inadvertently caused

interference to the less expensive, less selective radios close by that were

not tuned to KFSG. Those radio receivers made at that time had a limited

ability to separate strong stations from those with weaker signals. This

particular problem leads me to believe that KFSG was never at fault.

This also backs up the reply

I received in 1994, when I asked McPherson’s son, Dr. Rolf K. McPherson, about

the “minions of Satan” telegram his mother allegedly sent to Secretary of

Commerce Hoover. He said the story about the telegram is not true and never

took place. In his letter, Dr. McPherson wrote:

You refer to comments you have read that Aimee Semple

McPherson had correspondence with the Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover,

concerning infractions relating to the operation of radio station KFSG. This is one of the many rumors

which have persisted through the years. Mother never attempted to defy the law,

but always endeavored to comply with the rules. The statements you mention

certainly were not typical of her way of doing things. I might explain that the

equipment in those days was not always adequate, but the situations were

cleared as quickly as they could be. (Letter to the author from Dr. McPherson,

November 22, 1994)

His statement about the inadequate equipment in those days

describes the situation as it existed then, regarding radio interference and

trying to tune in the various weak and more powerful radio stations. It also

goes along with the fact that the problems were eventually solved, without KFSG

losing its license or being taken of the air, as Hoover claimed.

Regarding the common problem of radios trying to tune a station

without interference from another station, a 1922 article from John Hogan

called “Tuning the Radio Aerial” described the situation:

A receiver which has

the capability of close and exact adjustment to desired wave frequencies (or

wave lengths) will invariably aid in minimizing interference effects; with it

one will be able to receive clearly under many conditions where a broadly

adjusted receiver would be helpless to discriminate between desired and

undesired signals.”

Now, what is it that makes one receiver “sharply tuned” and another

“broadly tuned”? How does it happen that a sharply adjusted or

selective receiver will distinguish between arriving radio waves of only

slightly different frequencies? Why does a broadly tuned instrument accept,

with almost equal ease, signals whose frequencies are entirely different? The

replies to these questions include nearly the whole subject of tuning at radio

receiving stations." (Hogan 107)

Kenneth Ormiston, Aimee Semple McPherson in 1924

Kenneth Ormiston, Aimee Semple McPherson in 1924

KFSG HELPED SOLVE INTERFERENCE PROBLEMS

KFSG’s manager and chief

engineer Kenneth Gladstone Ormiston had radio experience dating back to 1914.

He was probably the best known and most knowledgeable radio broadcasting

engineer in Southern California, when he left KHJ and took the job as chief

engineer and supervisor for KFSG. He took his responsibility very seriously,

to keep KFSG operating on its assigned frequency of 1080 kilocycles, without

drifting up or down the dial, and to not use more than its 500 watts of

assigned output power from the transmitter. Before his death at age 42 in

1937, Ormiston was in charge of engineering for Hollywood station KNX.

Probably his biggest achievement at KNX was getting the station power increased

to 50,000 watts in 1934.

Ormiston acted quickly to

help station listeners who had problems with interference from other Los

Angeles stations, or had trouble tuning to KFSG’s frequency. He

also gave a lot of

advice to local radio fans who had receivers with poor selectivity, and

were

getting interference from KFSG, while trying to tune to other

stations. Within

four weeks of KFSG’s first broadcast (and two weeks after KFSG received

the

first letter from Radio Inspector Dillon about causing interference),

the Angelus Temple church bulletin printed this notice:

Radio fans and listeners-in

are requested to report in writing their reception of KFSG; also state

distinctly their ability to tune out KFSG and receive other stations at their

pleasure. We have been delighted with the reports that have come in on this

wise. There are a few however, that may need advice regarding the arrangement

of your sets. Such matters are taken up by our kind operator, Mr. Ormiston.

Our main point is to know you have control of your set and that you can get any

station without interference of the others. (Angelus Temple News, March 2,

1924)

These problems were also

addressed at a community meeting of radio fans held at Angelus Temple on

Monday night, March 17, 1924. The invitation was also made for

other local broadcast

stations and radio store dealers to attend. The notice in the

Sunday church

bulletin read in part:

Radio is a wonderful

science, which from our short experience, we learn still has many problems to

be worked out. Mr. Ormiston, our genial engineer and operator, has been very patiently

and kindly answering inquiries concerning reception, tuning, etc. We have

heard from a few locally with a smaller crystal set, have had difficulty in

separating the stations. We are anxious for one hundred per cent efficiency to

those interested in the Angelus Temple Radio. We are equally desirous not to

be heard, except by those who wish us. At this meeting, Mr. Ormiston and others

will deliver addresses. (Angelus Temple News, March 16, 1924)

The Los Angeles Times

reported on this meeting on March 23rd. In that story, it was

reported that Los Angeles crystal set listeners “have registered considerable

complaint that her (Aimee Semple McPherson) station is difficult to separate

from KHJ, KFI and the Bible Institute (KJS). This difficulty can only be

remedied by readjustment of single-circuit crystal sets to a fine degree of

selectivity.” (Los Angeles Times March 23, 1924) The article said that about

1,500 people were at the meeting, which showed a deep appreciation of radio and

a spirit of co-operation in solving its problems.

Besides the problem of

crystal set owners having trouble separating stations, listeners had to suffer

from noise and interference put out by many of the regenerative radios that

were sold in 1924. KFSG engineer Ormiston wrote about this in his monthly

radio column in the April 1924 Foursquare Bridal Call magazine. In the 1999

book Listening In by Susan J. Douglas, she describes the troubles

listeners had with regenerative sets:

“Often, they actually

interfered with themselves and with other nearby receivers because, in the

hands of the less technically astute, they didn’t just receive radio waves but

also generated them. In other words, listeners would inadvertently turn their

receivers into transmitters, producing horrible squeals and howls that made

their neighbors furious with them.” (Douglas 77) In Los Angeles and other large

U.S. cities in the mid-1920s, radio listeners trying to hear the various

stations often had endure a mass of hums and whistles caused by the

regenerative radios.

By October of 1924, Ormiston

wrote an article for Radio Doings magazine on how to build a crystal set

with good selectivity. Ormiston assured broadcast listeners that they didn’t

necessarily have to buy expensive receiving sets to enjoy radio. He wrote,

“The cheapest crystal set may be highly efficient, combining sensitiveness and

selectivity in a high degree and give satisfaction, even though there may be a

large number of local stations on the air. A crystal set is capable of selectivity,

and to encourage popular belief in this fact, we are describing this week what

we believe to be the most selective of crystal receivers.” (Ormiston 13)

And in January 1925, the

national magazine Radio in the Home did a feature story on KFSG and McPherson.

Dr. Ralph L. Power wrote, “When KFSG first went on the air, thousands of radio

fans registered emphatic and vigorous protest, because some non-selective sets

would not enable them to tune out the new station. But that’s all ancient history

now. Most of the people wouldn’t tune KFSG out now if they could.” (Power 24)

This tells me that the

problems which caused KFSG to interfere with the reception of other radio

stations in Los Angeles on some radios with poor selectivity were short-lived

and quickly solved, to the satisfaction of the Department of Commerce Radio

Inspector.

THE ORIGIN OF THE HOOVER TELEGRAM STORY

There is no record of Herbert Hoover or Aimee Semple McPherson

speaking or writing about the alleged “minions of Satan” telegram story during

the 1920s or 1930s. So, if McPherson did not send the legendary telegram to

Secretary of Commerce Hoover, and I can’t find any mention of it in any 1920s

media, then how did this fantastic story get started?

McPherson died in 1944 at age 53. The earliest mention of such a

telegram was made by Hoover, during a speech he made on the CBS Radio Network

on November 10, 1945. (Hoover 144) The occasion was the 25th

anniversary of radio. During the speech, Hoover told a story about a radio

station which had violated radio regulations during the 1920s (again, no

specific date or year is given), and he talks about a telegram which he claims

was sent to him by the woman who owned the station.

However, in this first version of the story, Hoover does not

mention any specific evangelist by name. He also does not specify the call

letters of any radio station or the city where this incident allegedly took

place. He only refers to the incident this way:

Once upon a time, there was an evangelist in a certain city upon

whom it dawned very early that heaven as well as the earth could be reached

with a broadcasting station. She bought an outfit and proceeded to broadcast

without restraint over all wave lengths. I sent an inspector to argue with the

lady that she keep on her own wave length.

Next, Hoover said, “I can give you approximately the telegram I

received from her.” He then proceeded with the words he claims were written by

the unnamed evangelist: PLEASE ORDER YOUR MINIONS OF SATAN TO LEAVE MY RADIO

STATION ALONE. YOU CANNOT EXPECT THE ALMIGHTY TO ABIDE BY YOUR WAVELENGTH

NONSENSE. WHEN I OFFER UP MY PRAYERS, I MUST FIT INTO THE RECEIVING SETS IN

HEAVEN. YOU DON’T KNOW THEIR WAVELENGTHS AND NEITHER DO I. STOP THIS

INTERFERENCE WITH ME AT ONCE. (Hoover 144)

A few more years passed, before the alleged telegram story came up

again. It was in 1952, when volume II of Hoover’s memoirs was published. In

Chapter 20, on The Development and Control of Broadcasting while he was

Secretary of Commerce, Hoover writes about McPherson and KFSG:

A vivid

experience in the early days of radio was with Evangelist Aimee Semple

McPherson of Los Angeles. One of the earliest to appreciate the

possibilities

in radio, she had established a small broadcasting station in her

Temple. This station, however, roamed all over the wave band, causing

interference and

arousing bitter complaints from the other stations. She was repeatedly

warned

to stick to her assigned wave length. As warnings did no good, our

inspector

sealed up her station and stopped it. The next day I received from her a

telegram in these words:

PLEASE ORDER YOUR MINIONS OF

SATAN TO LEAVE MY STATION ALONE. YOU CANNOT EXPECT THE ALMIGHTY TO ABIDE BY

YOUR WAVELENGTH NONSENSE. WHEN I OFFER MY PRAYERS TO HIM I MUST FIT INTO HIS

WAVE RECEPTION. OPEN THIS STATION AT ONCE. AIMEE SEMPLE MCPHERSON

Finally our

tactful inspector persuaded her to employ a radio manager of his own selection,

who kept her upon her wave length.” (Hoover 142-143).

For unknown

reasons, the wording in the second part of the 1952 version is slightly

different than the version Hoover gave in 1945. Again, Hoover gives no

specific date or year that this took place. The Hoover Presidential Library

archivist Matthew Schaefer told me that the incident took place sometime

between 1924 and 1927, when Congress passed the legislation that created the

Federal Radio Commission, taking up where the Department of Commerce left off.

In an email from

Mr. Schaefer, he stated, “Hoover’s Commerce files related to radio fill several

boxes, and a search of the correspondence for the years 1921-1927 did not turn

up the telegram.” He then added, “Since the telegram is lost to history, there

is no way to narrow the date.” But, the archivist also said, “Given Hoover’s

careful attention to documenting history, I’m inclined to believe the story is

true, even without the original telegram as the irrefutable evidence.” (M.

Schaefer, personal communication, April 7, 2003)

A CLOSE EXAMINATION OF HOOVER’S STORY

It’s interesting to me that Hoover called this incident “a vivid

experience in the early days of radio.” If such a vivid story actually took

place as Hoover claims, why isn’t there any mention of it or reporting on it in

the radio pages or other pages of the Los Angeles Times or New York Times?

It seems to me that if one of the most famous women in the nation, who also was

a famous radio personality, had sent this telegram to the man in charge of

regulating radio broadcasting, it would have been big news. I also feel that

if McPherson had sent such a telegram or was planning to do so, she might have

shared this information with her Angelus Temple congregation and over KFSG.

There seems to be no evidence of any other reporting of the alleged incident

during the 1920s. Then, the story suddenly showed up more than 20 years later,

as told by Hoover on the radio and in print.

Also,

did KFSG really wander all over the wave band, as Hoover claimed? So far, I’ve

found no evidence that this took place. We know that KFSG’s signal did cause

interference to those trying to hear KHJ and KFI, but there is virtually no

chance it was deliberate. As I previously stated, during those early years,

many radios located close to KFSG were not made well enough to separate a

strong nearby radio signal from other radio stations in Los Angeles that were

transmitting from other parts of the city. Did this situation “arouse bitter

complaints” from the other stations? That is unclear, but possible. But when

Radio Inspector Dillon said in his letter to McPherson, that his office was

getting complaints each day about interference caused by KFSG to the reception

of KHJ and KFI, some of those complaints may well have been from those radio

stations as well as from radio listeners. All of the broadcasting transmitters

in Los Angeles were located in the middle of the city, on the roof of the

buildings where each radio station was located. Each radio station, such as

KFI, KHJ, KJS, etc. likely had the same problem of interfering with other

broadcast stations, depending on how close a radio listener was to any given

station’s transmitting antenna. This was especially true of those who owned

crystal sets and other radios with poor selectivity.

In addition, I have been unable to find in the Department of

Commerce files, such as their monthly Radio Service Bulletins, any evidence

that KFSG was ever taken off the air, as Hoover contends, when he stated that

the Radio Inspector “sealed up the station.” It seems that this too, would

have been a featured story in the newspapers and radio magazines of the day.

The other part that doesn’t make any sense is Hoover’s claim that the Radio

Inspector got McPherson to “hire a manager of his own selection,” to keep KFSG

on frequency. The station already had a capable chief engineer-operator from

the first day it went on the air in February 1924, Ormiston.

I have also found no evidence that KFSG was “straying

off-frequency.” Since Ormiston left his job as KFSG engineer after two years,

at the end of 1925 or early-1926, it is possible the incident could have taken

place during 1926 or 1927 under the watch of another chief engineer. But, once

again, I have found no mention of any newspaper or radio magazine stories of such

troubles involving KFSG, McPherson and Hoover.

On the Hoover Presidential Library website, the story is repeated

in one of their online Museum Exhibit Galleries, which includes a short

discussion of radio and Hoover’s part in helping to regulate the new medium of broadcasting.

Following the story of McPherson’s alleged telegram to Hoover, it says,

“McPherson eventually eloped with the Commerce Department representative

dispatched to explain the realities of federal regulation.” This statement is

definitely not true.

TELEGRAM STORY INCLUDED IN RECENT BIOGRAPHY

In 2007, a book on Aimee Semple McPherson’s life was written by

Matthew Avery Sutton. It is called Aimee Semple McPherson and the

Resurrection of Christian America. This is the only biography of McPherson

which makes any mention of the alleged telegram, on pages 81 and 82. Mr.

Sutton’s source for the story comes from an interview with Hoover conducted by

the Columbia University Oral History Project published in 1951.

Sutton writes that radio audiences “could hear the evangelist all

over the AM band instead of her own frequency.” Again, I would dispute that

statement, or at least, say the statement needs clarification for historical

purposes. Radio Inspector Dillon’s letters to McPherson make no mention of

KFSG wandering all over the AM dial or of the KFSG transmitter being

“off-frequency.” KFSG was being heard at spots on the dial besides 1080

kilocycles because of some radios with poor selectivity. There was a practice

of “wave-jumping” or broadcasting on an unassigned frequency in the mid-1920s,

but this was more common in big midwestern and eastern cities, where certain

radio stations tried to find a less-congested spot on the radio dial to avoid

interference on their assigned frequencies.

There was no such situation on the Los Angeles radio dial of 1924

and 1925. By the end of 1925, there were 17 stations licensed in

the Los Angeles region. About a dozen of those radio stations were

on the air on a regular

basis, while the others were on only 2 or 3 days or nights a week with

50 to

100 watts. One, KFPR, owned by the L.A. County Forestry

Department, was only

on the air once a month, unless there was a fire emergency.

To reiterate, it is true that those who owned radios and lived the

closest to KFSG’s transmitter, may have heard KFSG clear across the dial, when

they tried to tune into KFI, KHJ, KNX, KJS, etc. But once again, Dillon

himself said that the problems existed with the more inexpensive radios and

crystal sets with little or no selectivity.

Sutton then writes that Commerce Secretary Hoover was “cracking

down on the many broadcasters who were engaged in this practice, and decided to

shut down McPherson’s station temporarily to compel her compliance.”

In my research so far, I have yet to find any evidence that the

Department of Commerce radio inspectors or Mr. Hoover “shut down” KFSG for even

one day. I am certain that if KFSG was taken off the air for one hour or one

week by anyone within the Department of Commerce for violating one of their

broadcasting regulations, such an event would have been reported in the radio

pages of the Los Angeles Times and other newspapers of that city, along

with radio magazines of the day such as Radio Doings, Radio Digest, Radio,

etc. If KFSG had been taken off the air temporarily or lost its license, the

Department of Commerce would have included such an action in one of their

monthly Radio Service Bulletins, but I have not found any such action against

KFSG listed in those publications. Also, the KFSG license file copied for me

by the National Archives does not include any such documents regarding any

Department of Commerce punishment against the radio station or McPherson.

As for the alleged telegram, Mr. Sutton does carefully state in

his book that because of the alleged action to take KFSG off the air, “Hoover

claimed that she (Mrs. McPherson) had telegrammed him in response,” and he then

quotes the words from the supposed wire which Hoover quoted in his 1952

memoirs. Sutton ends the telegram story with, “Shortly thereafter,

nonetheless, she complied with his directives.”

Again, I have seen no proof in the KFSG license files, newspapers

of 1924-1927, radio magazines of the day or the files at the

International Church of the Foursquare Gospel that any of the above ever

took place. Steve

Zeleny, archivist for the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel,

said

in an email that nobody that has ever worked for KFSG or the church has

ever

written anything about the telegram story. As for the claim by

Hoover that “we

repeatedly warned her (McPherson) to stick to her assigned wavelength,”

Zeleny

wrote, “It makes no sense for her/KFSG to broadcast at random

wavelengths, ‘all

over the wave band,’ because she wanted listeners and advertised that

they

should tune in to 278 meters or 1080 kilocycles for KFSG.” (S.

Zeleny,

personal communication, July 19, 2010)

I would add that KFSG chief engineer Ormiston was a “by the rule

book” serious broadcasting engineer. Judging by all that I’ve read on his

radio career, he would never have allowed KFSG to stray off frequency or

deliberately cause interference to other radio stations. He probably would

never have allowed McPherson to send such a telegram to Hoover, if he could

help it.

Radio czar Hoover listening to a radio, circa 1922. Source unknown.

Radio czar Hoover listening to a radio, circa 1922. Source unknown.

IS THE TELEGRAM STORY REALLY TRUE?

If such a telegram was sent by McPherson to the Secretary of

Commerce or any Radio Inspector at the Department of Commerce, why is there no

copy to be found so far in any license files of KFSG, the Commerce Department,

the FCC, the National Archives or at the Hoover Presidential Library? And, if

the incident never took place as Dr. McPherson stated and my research has

determined, why would Hoover tell such an inaccurate story, when he was known

for striving to document history accurately?

Since this is the only published biography on McPherson which

includes the story of the alleged “minions of Satan” telegram, Steve Zeleny

asked Sutton for me, about the inclusion of the telegram story in his book.

Here is his reply:

This may well be

little more than a fun story that Herbert Hoover liked to tell with some

exaggeration. I tracked down the 1950 oral history, which was the best I could

do. That is why I chose my words carefully in the book: “Hoover

CLAIMED...”

There are lots of reasons

why Herbert Hoover may not have mentioned the telegram sooner than 1945—when

he was running for office, he needed conservative, Midwestern, Republican

votes. Why antagonize Aimee’s people? Especially in the context of the huge

fights over radio regulation in the late 1920s that were really upsetting

fundamentalists. All of which is to say, this may well be a myth along the

lines of riding a motorcycle in church, but I am not sure how you can verify

it. (M.A. Sutton, personal communication, June 27, 2007)

Again, if Hoover chose not to

talk about the telegram sooner than 1945, why didn’t McPherson ever talk or

write about it? Why was the alleged incident never reported in the radio pages

of the newspapers or important radio journals such as Radio, if it truly

took place?

I next checked with the

archivist at the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel, which McPherson

founded. I asked Zeleny about McPherson’s alleged telegram to Herbert

Hoover. Did she ever use the phrase “minions of Satan” at any time during her

years as the head of Angelus Temple and KFSG? Zeleny wrote to me the

following:

Regarding

her “track record” for using that phrase, there is none. Our

database consists of approximately 3-million pages, all of which are

keyword/phrase/Boolean searchable. I just performed a search for any use of a

phrase exactly like, or similar to “minions of Satan” in her books,

her sermons, the corporate minutes, the other corporate documents, or any of

the Foursquare magazines and newspapers from 1917 through 1945. In those

searches I found one “hit” and that was from an article written by

someone other than Aimee Semple McPherson. With her incredible speaking

itinerary, where she had to speak the same message many times in different

locations, often spoke three times per day (sometimes more), and had much of

what she said recorded by her personal assistant, I can only say that I would

find it highly unlikely that she would have used the phrase “minions of

Satan” once and only once in her entire recorded lifetime—and that in a

letter to the Secretary of Commerce and future president. There are many times

in many sermons where she could have used it and it actually would have fit,

but she never did. Remember, she was incredibly popular and kind and loved. I

doubt that she got that way by calling people ”minions of Satan.” It

would be totally contrary to everything we know about her personality. (S.

Zeleny, personal communication, November 9, 2009)

Steve added that their

database shows that McPherson talked about Satan or the devil more than 1,500

times, and the phrasing in the alleged telegram is unlike anything in their

records of her sermons and speeches.

DID HOOVER TAKE ACTION AGAINST KFSG?

In my search for any shred of

truth to the telegram legend, I asked radio historian Thomas H. White if

Hoover ever took matters into his own hands, when a radio station was

accused of violating

Department of Commerce radio regulations. I also wanted to know if

radio

station owners tried to get Secretary Hoover involved directly when

their

stations had violated any rules, instead of dealing with the local radio

inspector. Here is White’s reply:

Some station owners tried to

go directly to Hoover, but as far as I know he always refused to get directly

involved, because 1) the Secretary of Commerce had better things to do than get

involved in local problems—that’s what the local radio inspectors and the

Bureau of Navigation staff were for, and 2) in any event, he was always nervous

about the legal limits as to how much legal authority he actually had. (T.H.

White, personal communication, July 25, 2010)

In Bensman’s book The

Beginning of Broadcast Regulation in the Twentieth Century, there is

some testimony by Hoover at the 1923 Congressional hearings for the

White-Kellogg bill that is a good summary for how they handled things. At the

hearing, Secretary Hoover again stressed the main problem in the proposed

legislation:

I do not think it would

be any exaggeration to say we are receiving thousands of protests monthly over

questions of interference. We are engaged in endeavoring to compromise and

compose the difficulties between broadcasting stations, on a purely voluntary

basis, all over the country. Some cities have as high as 20 broadcasting

stations, all interfering with each other, and our agents have endeavored at

one time and another to get them into voluntary agreements as to the division

of the time and other methods of preventing interference; but we are totally

without the necessary authority to effect results. And this is not a case of

regulation as against the will of the industry, and the wish is that there

should be some regulation by which these problems can be disentangled at least

to some extent. It is unique in the way of regulatory legislation.

(Bensman 62)

After reading the paragraph

above, Zeleny, the archivist for the International Church of the Foursquare

Gospel, commented in an email to me that there are three key points “in

Hoover’s own words” which seem to indicate that the telegram story is untrue:

The line “but we

are totally without the necessary authority to effect results”

completely

contradicts the basis of the story that they (The Department of Commerce

or Hoover) did temporarily shut down KFSG. That he (Hoover) personally

testified of handling

these situations through compromise rather than hard-ball tactics,

opposes the

basis for the KFSG story. And that this was a systemic problem also goes

against the idea of him (Hoover) leaning hard on one station and not

treating

others in the same manner. With this testimony in evidence, I

think we’ve

reached the point where the TV show Mythbusters would now declare this

story to be BUSTED. (S. Zeleny, personal communication, July 26, 2010)

I would also like

to point out that in Bensman’s book on early regulation of broadcasting,

he too

wrote about the telegram story as if it were true. But Bensman

said that the

alleged incident took place in 1925 (again no specific date). He

also stated

that one of the station owners who complained about interference from

KFSG in

1925 was Reverend “Fightin’ Bob” Shuler of KGEF, at Trinity Methodist

Church in Los Angeles. (Bensman 137) The reason this could not be

true, is that KGEF

was not licensed to broadcast until December of 1926 and was not on the

air

until January of 1927!

In another book

by Hal Erickson on the history of religious radio and television, he also wrote

about the telegram story, but said it took place in 1927, without giving a

specific date. (Erickson 127) If it was before February of 1927, that was

during the time a Federal Court ruled that under the Radio Act of 1912,

Secretary Hoover had no power to deny station licenses, assign frequencies or

transmitter powers for any radio station. After February of that year, the

Federal Radio Commission was formed to regulate broadcasting.

HOW DID SHE

REALLY FEEL ABOUT HOOVER?

In a search of

Foursquare publications from the 1920s to the 1940s, there is not one instance

in which Herbert Hoover was ever referred to in a less-than-positive light by

Aimee Semple McPherson. (S. Zeleny, personal communication, August 17, 2010)

The articles which quote McPherson about Herbert Hoover recommended not only

voting for Hoover for President of the United States in 1928, but praised him for

his support of the Bible, Sunday School, The Ten Commandments and his appeals

to spiritual values. Here are two examples:

He has shown the spirit of Christ in his service for

others.(Foursquare Crusader, October 17, 1928)

Experience, Ideals and

Program Make Candidate Logical Victor

Herbert Hoover should make a

better president for this country than Alfred E. Smith. There are many

reasons

for this, the main ones being the

difference in training, experience and ideals of the two men. Laying

aside

entirely the matter of religious differences, Mr. Hoover is the man of

the hour

right now. His training has been in big business; he has a record

of fine

accomplishments behind him. And there is no other business, except God's

business, quite important in the world now as the business of the United

States of America. Mr. Hoover's training and past actions also indicate

that he will

be quite zealous in carrying out the Lord’s business. (Foursquare

Crusader,

October 31, 1928)

CONCLUSION

It has been 87 years since

the first broadcast of KFSG and 60 years since Herbert Hoover’s memoirs were

first published. I believe I have clearly shown that there are several gaps in

Herbert Hoover’s story about the alleged telegram he claimed was sent to him by

Aimee Semple McPherson. Those gaps include his claims that KFSG was

transmitting on different wavelengths on purpose, that KFSG was ordered off the

air and “sealed up,” and that the alleged incident led the Department of

Commerce Radio Inspector to get KFSG to hire Kenneth G. Ormiston as its

engineer and station manager. None of those statements are true. Regarding Ormiston,

he had been working for KFSG since the station went on the air in February of

1924.

The gaps which I have

outlined create a huge amount of doubt that this incident ever took

place, at

least the way in which Hoover said it happened. The gaps also

bring Hoover’s accuracy into question. It is amazing to me that

over the past 60 years, this

story has been so widely accepted as completely true, without anyone

questioning its accuracy or checking into what really took place at KFSG

during

the period between 1924 and 1927. I’m certain this is because of

the

untarnished reputation of Hoover, which made the story seem true to

people like

Barnouw and Bensman.

I believe that the so-called

telegram incident never occurred. McPherson’s radio station did have some

interference problems during its earliest time on the air, but so did other

radio stations across the United States in 1924 and 1925. And there were

complaints from listeners of KHJ, KFI and KJS about interference from KFSG, and

possibly officials from those stations. But the interference was caused by the

crystal sets and other radios in Los Angeles with poor selectivity which could

not separate KFSG while being tuned to other stations. It was clearly not

because KFSG’s transmitter was wandering off frequency all over the AM band, as

Hoover stated. But the problems occurred during the first few months after

KFSG went on the air. By January of 1925, the same problems had been solved

and nearly forgotten.

The overall problem for me is

trying to stamp out a rumor that sounds so good and has been around since the

1950s. I’m trying to “prove a negative” where the people involved are dead and

there are limited records. Sutton said much the same thing in an email in

2007. After writing that I would have a hard time proving a negative, he said,

“How can you prove that something does NOT exist?” (M. A. Sutton, personal communication,

June 27, 2007) It is also difficult to get to the truth, when the source of

the story is a former president who was in charge of radio during much of the

1920s, while at the same time, overlooking McPherson’s colorful past.

Was there really a telegram

sent to Hoover from Aimee McPherson, as Hoover claimed? And if so, what became

of it? Or, could another person have sent Hoover such a telegram? Another

email from Steve Zeleny, archivist for the International Church of the

Foursquare Gospel, mentions such a possibility was brought up in a 1980 letter

from Mr. Raymond Cox to Rolf McPherson, Aimee’s son. In the letter, Cox wrote,

“So I wonder if sent, it was actually authored by another person, perhaps

Minnie Kennedy (Aimee’s mother). Sister just didn’t talk that way.” (S.

Zeleny, personal communication, July 20, 2010)

Why is there no copy of this

supposed telegram to be found so far in the KFSG license files at the National

Archives or at the Hoover Presidential Library, when other important telegrams

and letters were kept by the Department of Commerce and copied? Was there a

private telephone conversation between McPherson and Hoover or did she write

him a letter? I have also shown substantial evidence that there are no records

of any violations of radio regulations by KFSG or that KFSG was ever ordered

off the air by the government.

Could it be possible that Hoover’s memory of what the problems were concerning KFSG in 1924 was not entirely

accurate, by the time he made the 1945 speech and wrote his memoirs in the

early-1950s? Whatever Radio Inspector Dillon told Hoover in 1924 about the

exact nature of KFSG’s interference problems, may have been very different from

what Hoover remembered more than 20 years later.

In addition, I have shown

that three periodicals with the most extensive coverage of the period, the New

York Times, the Los Angeles Times and Radio magazine make no

reference to the alleged events between McPherson and Hoover. I believe this

is fairly strong evidence that the telegram story as told by Hoover never took

place. However, in all fairness, I must say that even if the most widely read

newspapers of the day and the most widely read radio magazine of the time never

wrote about such a telegram, they also did not report on the letters from Radio

Inspector Dillon to KFSG in February of 1924. But, the interference problems

common to radio broadcasting across the United States in 1924 were known to Los

Angeles radio fans, as the Angelus Temple church bulletins in March and April

1924 have indicated and the Los Angeles Times reported on March 23,

1924.

I believe it is finally time

to bury this story. The legend of the McPherson telegram to Secretary of Commerce

Hoover does make for good story telling. However, I think once all of the evidence

and lack of evidence is examined, as I hope I’ve been able to do to your

satisfaction, you’ll agree that is exactly what it is. It is just a story and

another myth from the earliest days of radio.

Works Cited

Angelus Temple News, March 2 and March 16, 1924

Barnouw, Erik. A Tower in Babel-A History of Broadcasting in the United States to 1933. (p. 180) Oxford University Press 1966.

Barnouw, Erik “Historical

Survey of Communication Breakthroughs.” Proceedings of the Academy of

Political Science Vol. 34 No. 4, The Communications Revolution in Politics

(1982) pp. 13-23

Bensman, Marvin. The

Beginning of Broadcast Regulation in the 20th Century. (pp. 62,

75-76, 137). McFarland and Company, Inc. 2000.

Douglas, Alan. Radio

Manufacturers of the 1920s Volume 1. (pp. xx-xxi) Vestal Press 1988.

Reprinted from Radio Retailing March 1928. (pp. 36-37). Print.

Douglas, Susan J. Listening

In Time Books, a division of Random House, Inc. 1999 (p. 77)

Erickson, Hal Religious

Radio and Television in the United States 1921 to 1991 (p. 126-127)

McFarland and Company, Inc. 1992

Frost, S.E. Education’s

Own Stations. (pp. 78, 142, 149). Ayer Publishing 1971. Reprint of the

book from 1937.

Halper, Donna L. Invisible

Stars: A Social History of Women in American Broadcasting. (pp. 68-69)

M.E. Sharpe 2001

Hoover, Herbert. “On the

Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of Radio.” Addresses Upon the American Road

1945-1948. (p. 144) Stanford University Press. 1949

Hoover, Herbert. “Development

and Control of Radio Broadcasting.” The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover—The

Cabinet and the Presidency Volume Two. (pp. 142-143). The MacMillan

Company 1951

Hogan, John. “Tuning the

Radio Aerial.” Radio Broadcast May 1922 (p. 107) Print.

“Mrs. McPherson Is Hostess

For Housewarming.” Los Angeles Times March 23, 1924 (p. A9)

Ormiston, K.G. “A Selective Crystal Set.” Radio Doings October 25, 1924 (p. 13)

Power, Dr. Ralph L. “Angelus Temple Is Unique Among Broadcasters.” Radio in the Home January 1925 (p. 24)

Print.

“Problems Face Col. Dillon in

New Radio Post.” Los Angeles Times March 6, 1927 (p. B8)

Radio Service Bulletin January 1924 to December 1927. Issued monthly by the

Bureau of Navigation, U.S. Department of Commerce.

Sutton, Matthew Avery. Aimee

Semple McPherson and the Resurrection of Christian America. (pp. 81-82).

Harvard University Press 2007

Wacker, Grant. Heaven

Below: Early Pentecostals and American Culture. (p.33) Harvard University

Press. 2003

Jim Hilliker is a former radio broadcaster. He has researched and

written about the early history of Los Angeles area radio for more than

20 years.

Email:

jimhilliker@sbcglobal.net.

Photos on this page are courtesy of Steve Zeleny, archivist,

International Church of the Foursquare Gospel, Los Angeles.

|