KGFJ - Los Angeles

The Original 24-Hour Radio Station

By Jim Hilliker

Copyright 2014

(Author’s note: This document is a revised version of

my November 21, 2002 article “The Forgotten All Night Shift.” It was

first published on the website LARadio.com. This essay was intended to

celebrate the 85th anniversary of KGFJ in Los Angeles becoming the

first regular 24-hour broadcaster in the United States, but I was not able to

finish in time. I also will include as many details as possible about other

24-hour radio stations in Los Angeles and around the U.S. that operated between

1927 and the 1950s, which I did not fully research in 2002. I’ve also included

some details about AM band DXing, the hobby of tuning for distant radio

stations, usually after dark.)

Introduction

When I wrote my original article in 2002 on KGFJ’s all-night broadcasting

legacy, I assumed that the station was running a “24-hour-a-day” schedule in

November of 1927. While the station was indeed the first in the United States to broadcast a regular all-night program of phonograph records between

midnight and 6:30 a.m., KGFJ was still sharing time with KFVD-San Pedro.

KGFJ did not technically become the first regular 24-hour-a-day radio station

until three months later, on March 1, 1928.

Today, we take for granted the fact that our favorite radio

stations in Southern California will be on the air all day and all night.

Because we now live in a society that is more connected to a 24/7,

around-the-clock lifestyle than ever before, it's hard to comprehend that at

one time, this was not always the case. In broadcasting's infancy,

finding a radio station on past midnight was a rare occasion!

Today, the former KGFJ has the call letters KYPA and operates on 1230 kHz. It is owned by

Multicultural Broadcasting.

It was in November of 1927 that a U.S. radio station first decided to broadcast during the "all-night" hours after

midnight on a regular basis. There were a handful of stations that did

this on an irregular basis prior to 1927. A book on the history of

all-night radio said WDAF in Kansas City may have stayed on the air for 24

hours in 1922. The station did broadcast the Coon-Sanders Original

Nighthawk Orchestra, starting in late-1922, but they usually went off the air

at 1:00 a.m. Also, a reference book on radio history said that in

1923, KYW-Chicago called itself "The 24-Hour Station." I

found evidence that KYW was broadcasting news bulletins from a Chicago

newspaper past midnight, but I’ve found that the station would turn the

transmitter on and off every half hour or so, to read news bulletins when they

came in off the wire service. It was not one continuous all-night

broadcast. In 1925, there’s some evidence KYW was broadcasting jazz band

remotes overnight, but I’m not sure how long that lasted. However,

these claims are difficult to prove and, if true, those radio stations didn't

stay on the air regularly for 24 hours very long. Radio historian

Elizabeth McLeod agrees with my research, which shows a low-powered Los Angeles station holds the honor of being the first to stick with regular all-night

broadcasts 7-days-a-week for a long period of time, and making 24-hour

broadcasting profitable.

A Pioneer in 24-Hour Broadcasting

The first radio station in the United States to broadcast

24 hours a day each day regularly was KGFJ- Los Angeles. A 1962

station ID for KGFJ proclaims itself as “The original 24-hour

station.” If it was not the first radio station to stay on the air

24-hours-a day, it was most likely the first to gain a strong foothold in the

world of 24-hour broadcasting and get attention from fellow broadcasters and

listeners alike, for being on the air all night.

It was a big step to take at the time, when most

radio listeners were asleep during the hours past midnight, with the exception

of Friday and Saturday nights. There was also some concern that the early

radio transmitters could not operate consistently if they were left on for 24

hours or longer, without tubes burning out. There was also the business

of trying to bring in commercial advertising for those overnight hours.

KGFJ was alone on the radio dial past midnight, at

first. But, a few stations in the Southland and across the nation

gradually ventured into the practice of all night broadcasting from 1928 to

1935. Some didn’t stick with it too long. But KGFJ kept their

transmitter running all day and all night, while gaining some devoted listeners

and also some critics.

When radio broadcasting started in the early-1920s, it was

a simpler time in America. The lifestyle was different, as people went to

work at a later hour in the morning than is common now. Radio

stations often went on and off the air several times a day.

Many first went on the air only during the late afternoon and evening

hours. Friday and Saturday nights were also the main times that radio

stations broadcast music and entertainment programs past 11 pm or

midnight. Even in the largest cities such as New York, Chicago and Los Angeles, stations rarely extended their airtime past 2 or 3 a.m., when many radio

stations had popular late night entertainment and music programs.

By 1925 to 1927, the stations in Los Angeles with the

largest number of announcers, sales people, writers, and engineers began

broadcasting from early morning until about 10 to midnight, but still not much

after that hour, except on special occasions such as New Years Eve.

The Beginning of a New Radio Station

In February of 1927, a 23-year-old USC student and ham

radio enthusiast, Ben

S. McGlashan, and his Los Angeles High School friend Calvin J. Smith,

put a new radio station on the air in Los Angeles.

They got their broadcasting license February 5, 1927, during a period

of "non-regulation" for radio, just before Congress passed

legislation to form the Federal Radio Commission, the predecessor to the

FCC. This lack of rules made it possible for McGlashan to choose his own

frequency for KGFJ. He had his new station transmit its signal on the

“split-frequency” of 1375 kHz with 100 watts of power.

Ben had some broadcasting experience in 1925 and '26, as

"Big Brother" on KFWB, hosting that station's daily children's

program and he also was employed as one of KFWB’s broadcast engineers.

While working at KFWB, he decided he wanted to put his own radio station

on the air.

The call letters assigned to his station were KGFJ,

which put out its first broadcast into the airwaves from the roof of the Odd Fellows Temple at Washington Blvd. and Oak St. Like many radio stations of

that era, a slogan that listeners could identify with was soon adapted from the

call letters: "Keeping Good Folks Joyful."

The station was first mentioned in the radio column of the Los

Angeles Times on February 18, 1927. It was still not on the air 13 days

after it was licensed. Radio columnist Dr. Ralph L. Power wrote, “KGFJ is a

new 100-watt station on top of the Odd Fellows Temple in Los Angeles using a

218 meter wavelength. The set is being operated as a commercial station by its

owner Ben S. McGlashan, former technical engineer at KFWB. No program hours

have yet been announced, but tests have shown the station to have particularly

good modulation quality.”

McGlashan's friend, Calvin Smith, was KGFJ's first

general manager. They had scraped together $200 to put the station on the

air. Some of their first equipment was salvaged from a defunct

broadcaster, KUS, which was on the air in 1922 and 1923 for the Los

Angeles City Dye Works and Laundry Company, before that station went

dark. By the time of the first KGFJ broadcast, McGlashan was using pieces

of broadcast equipment from at least six Los Angeles area stations. In the

early days of KGFJ, the station was broadcasting a very short schedule.

Ben and Cal went on the air only when they had something to say, then went off

the air to spend the rest of their time trying to sell commercials so they

could return to the air the next day.

During the early 1930s, Smith left KGFJ to work for

E. L. Cord as station manager at KFAC. Smith had that job with KFAC, until

Cord sold KFAC AM and FM for $2 million in December of 1962. After Smith

left KGFJ, an older ham radio friend of McGlashan, H. Duke Hancock, served as

KGFJ's assistant manager for many years. Hancock had operated a

"wireless radio station" at the end of the Venice Pier as early as

1912.

I still have not determined when KGFJ’s first regular

broadcast took place. But, it likely was broadcasting by the time the February

26, 1927 issue of Broadcast Weekly was mailed to a radio hobbyist in

Santa Cruz, California. This magazine is in my collection of radio

memorabilia. On several pages of the magazine are call letters written in

pencil and some program details from numerous stations across the United States,

plus at least one foreign station, PWX in Havana, Cuba. On page 31, this DXer

wrote, “KGFJ, Chateau Ball Room, Odd Fellows Main Floor, Oak Street, 3 blocks

west of Figueroa.” I believe KGFJ’s signal was heard by this DXer, as he wrote

the call letters on the top of the page, along with calls of WSM-Nashville,

WCCO-Minneapolis, KOMO-Seattle, WGN-Chicago and KMOX-St. Louis on other pages.

He also wrote some of their dial settings for future reference. Other Los Angeles area stations this person heard include KHJ, KMIC-Inglewood and KELW-Burbank.

KGFJ Starts Broadcasting All Night

Toward the end of 1927, McGlashan decided to keep his

station on all night, by selling airtime for a program of KGFJ broadcasting

nothing but recorded music, interspersed with the sponsor's advertising

messages. McGlashan was an astute young businessman and his goal was to

make KGFJ successful by selling commercial airtime to advertisers. This

practice took some time to gain popularity, but was becoming common by the

late-1920s.

The first mention of the radio station staying on the air

all night was in the Los Angeles Times radio column of November

17, 1927, with the headline, "ALL NIGHT PROGRAM." The brief item

said:

"This week's interest in radio locally brings no

startling developments, although it does record a few items of interest.

For instance, over at KGFJ, they have just inaugurated an all-night program of

record selections. Starting at midnight, the broadcast of phonograph

numbers continues until 6:30 a.m., when the regular morning breakfast program

commences."

While we don’t know the exact day of this historic occasion

in radio, it’s likely KGFJ’s first all-night broadcast took place a few days

before November 17th. The first time the Times

Radio Log page listed

the program was on November 22, 1927, with the first item, "Midnight -

6:30 a.m., KGFJ, Phonograph record music."

After the Federal Radio Commission ruled that KGFJ did not

have to share time with KFVD in San Pedro, KGFJ became a full-time

24-hour-a-day radio station on March 1, 1928. KGFJ's slogan was quickly

amended to "Keeping Good Folks Joyful – 24 Hours-A-Day."

The 100-watt station moved from 1375 to 1390 kHz on April 22, 1927.

The Federal Radio Commision changed KGFJ’s frequency again on June 15, 1927,

to 1440 and had KGFJ share time on that frequency with KFVD-Venice.

The FRC decided to move KGFJ from 1440 to 1410 kHz on March 1, 1928, which

allowed KGFJ to broadcast 24 hours and gave KFVD its own frequency.

Eight months later, the FRC changed KGFJ’s frequency again

to 1420 on the radio dial on November 11, 1928. Another

frequency change was ordered by the FRC to 1200 kHz on November 15,

1929. KGFJ moved to 1230 on the AM dial March 29, 1941.

KGFJ’s transmitter power was boosted over the years on the Class

IV/local frequency (now known as Class C) to 250 watts day and night in 1947,

1000 watts day/250 night in 1962, and in 1984 to 1000 watts day and night).

However, from 1947 to 1986, 1230-AM had to drop power to 100 watts to protect

100-watt KPPC at 1240 kHz. in Pasadena during KPPC’s broadcast hours on

Wednesday nights and Sundays from 6 a.m. to midnight. (The Pasadena

station on 1240 was only 10 miles from the KGFJ transmitter, and was licensed

in 1924 before the FCC was in charge of regulating radio, so KGFJ was obligated

to “power down” twice a week, in order to prevent interfering with KPPC’s

signal.)

The owners of KGFJ changed the call letters to KKTT (“The

Katt”) on October 10, 1977. The call letters were changed back to KGFJ on

October 15, 1979. Finally, the call letters changed from KGFJ to KYPA for

“Your Personal Achievement” on May 1, 1996.

Being the only station in the entire nation to stay on the air

all night brought fame to KGFJ and an increase in listeners throughout the

years. After all, no other station in L.A. or anywhere else in the USA stayed on after midnight regularly at the time. When he started this new idea of

all-night broadcasting 7 days a week in 1927-1928, McGlashan was quoted in Radio

Doings magazine in 1930 as saying, "Nobody else would be crazy enough

to do it."

In August of 1928, KGFJ's all-night show was called the

"Kemper Nite Owl Program," likely named after the main sponsor of the

broadcast of recorded music. No announcer for this show was listed.

By October of 1929, KGFJ was simulcasting several shows with KFOX-Long Beach, including the overnight "Nite Owl Program," which started at 1 a.m. each

day, after the Apex Nite Club remote at midnight. The radio listings show

that M.B. Cosby was KGFJ's "resident Nite Owl" and likely the

announcer on the overnight show.

Joey Starr and his Orchestra performing at KGFJ in 1927 (both photos).

Joey Starr and his Orchestra performing at KGFJ in 1927 (both photos).

(USC Digital Library Special Collections)

All-Night Radio and the DXer

During the 1920s, many radio fans became obsessed with

trying to tune in stations from distant parts of the United States and in some

cases, from overseas. In the earliest years of radio, strong local

stations did not exist in every area, and radio fans often had to hunt for

listenable radio programming after dark, when AM signals could skip hundreds or

thousands of miles, especially in the colder winter months. Their hobby was

called DXing (ham radio shorthand for distant or distance). The DXers

tuned up and down the radio dial after dark and sometimes well past midnight,

“fishing” for far-away radio stations. Much like channel surfing today, when

they heard a station identification, they moved along the dial to another

distant signal, despite often putting up with noise and fading. Many also

wrote cards or letters to the stations with details of their reception, to

prove they heard a particular station. Often, stations sent the DXers

unique cards or letters to verify that their reception reports were

correct. When network radio and local stations improved with better

overall programming and stronger signals with higher power by 1930, the

popularity of tuning for “out-of-state” stations decreased a lot, but the hobby

of DXing continued into the 1930s, ‘40s and beyond, though with fewer people

taking part.

When the Federal Radio Commission was formed in 1927

to reduce congestion and interference on the AM Broadcast Band, there were 732

radio stations on the air in the United States. By November 11,

1928, that number was reduced to 585 stations on the air. By 1938, the

number of radio stations increased to

723. Compare that number to the more than 4,700 radio

stations on the AM band as of 2013!

When KGFJ began its 24-hour programming schedule with all

night music from phonograph records, the DXers “fishing” for rare, far-away

radio stations in the late-night, overnight and pre-sunrise hours, had a fair

chance of hearing a west coast station, as they tuned their radios in the

Midwest or eastern states. Not only was there less congestion and less

interference throughout the AM band than we have today, but there was much less

man-made noise to interfere with radio reception such as we get today from

computers, light dimmers, televisions, etc. Also, there were very few

directional antenna systems in the 1930s. With non-directional antennas

sending skywave signals in all directions, radio hobbyists had a fairly good

chance, especially in the colder winter months, to hear virtually every radio

station in the United States, if the conditions were right.

On the East Coast, most stations in the 1930s went off the

air by midnight or 1 a.m., and the same thing took place with stations in the

Central and Mountain Time Zones. By 2 a.m Eastern Time, DXers back East

would often be able to hear a variety of stations from California, Oregon and

Washington. Not only were the 50,000 watt powerhouses such as KFI being

received, but regional stations from 500 to 5,000 watts, and yes, even local 50

and 100 watt stations such as KGFJ on 1200 kHz were heard quite often

across the USA.

During 1928, a young DXer named Gene Martin kept a logbook

of the stations he heard late at night from his home in Dallas, Texas. In

the 1990s, Mr. Martin sent me a list of 22 Los Angeles area radio stations he

heard while tuning around the Broadcast Band in 1928. One of the

radio stations he listed in his logbook was 100-watt KGFJ. Mr. Martin

wrote this note next to the KGFJ entry: “This was one of the first all-nighters

in the United States.”

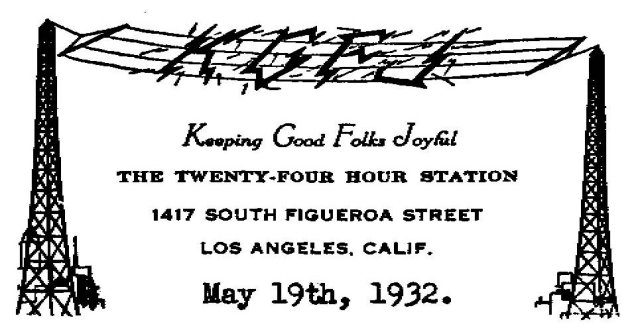

KGFJ letterhead. An image of the entire page is here.

Image courtesy of The Committee To Preserve Radio Verifications.

KGFJ letterhead. An image of the entire page is here.

Image courtesy of The Committee To Preserve Radio Verifications.

Late 1920s and 1930s Radio Overnight

In 1929, a few other radio stations in Los Angeles followed

KGFJ's lead, by playing records overnight. The radio page of a Glendale newspaper dated April 17, 1929 lists KGFJ, along with KMIC-Inglewood and

KGFH-Glendale as broadcasting phonograph records from midnight to 7

a.m. In addition, KPLA in Los Angeles stayed on the air with music

from phonograph records from 1 a.m. to 6 a.m. KGFH would be off the air

for good only a few months later, after the Federal Radio Commission refused to

renew their station license. By the end of the year, KPLA was sold to

Earle C. Anthony and became station KECA.

By the middle of 1930, KGFJ moved into new quarters,

with studios and offices on the top of the J.V. Baldwin Building in Los Angeles

at 15th Street at Figueroa, or 1417 South Figueroa Street. The

transmitter and antenna remained at Washington at Oak St., where it stayed

until January 14, 2009, nearly 82 years. That’s when the station on 1230

kHz (KYPA since 1996) moved to the transmitter site of 50,000 watt KBLA-1580

in Los Angeles, with 1,000 watts of power from KBLA tower number 6, from its

six-tower directional array. The signal was later changed to a

two-tower directional pattern from KBLA’s number one and two towers. This

provides a stronger radio signal in the Koreatown area of Los Angeles than the

old flattop wire antenna. It should also be noted that KYPA-1230 and

KBLA-1580 are owned by the same company.

In San Francisco, KJBS-1070 kHz (now KFAX-1100),

started broadcasting all night on April 19, 1930 with all music from phonograph

records. KJBS was allowed to broadcast during the hours that

WTAM-Cleveland on 1070 was off the air. The station billed itself as the

“midnight to sunset station.” Their after midnight “Owl” program was the

first all-night radio show in Northern California. By November 1, 1930,

KMTR-570 in Hollywood was on all night playing records from 1 to 6 a.m.

KMIC had given up all-night broadcasting and KPLA had changed owners and call

letters on November 15, 1929, to KECA-1430 for the initials of Earle C. Anthony,

who also owned KFI. KECA was usually off the air by midnight.

Also, I have a copy of a QSL letter to a DXer in New Jersey

from KTM-780 in Los Angeles that shows they were on the air at 3:00 a.m. in

February of 1931. Another QSL letter to a DXer in Maryland verifies

overnight reception of KMTR-570 in Hollywood in February of 1931. The

last sentence of the letter states that KMTR was a 24-hour radio station and

the DXer was tuned to their all night record request program from 1:00 to 6:00

a.m.

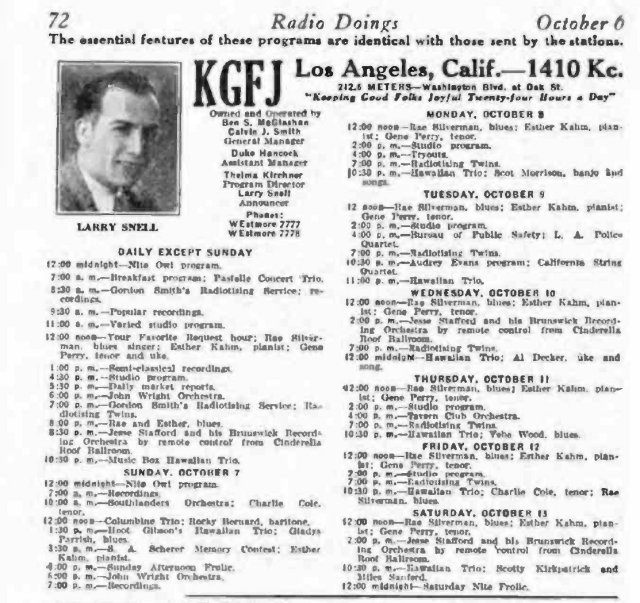

The KGFJ program schedule from Radio Doings, Oct. 7, 1928. larger image

The KGFJ program schedule from Radio Doings, Oct. 7, 1928. larger image

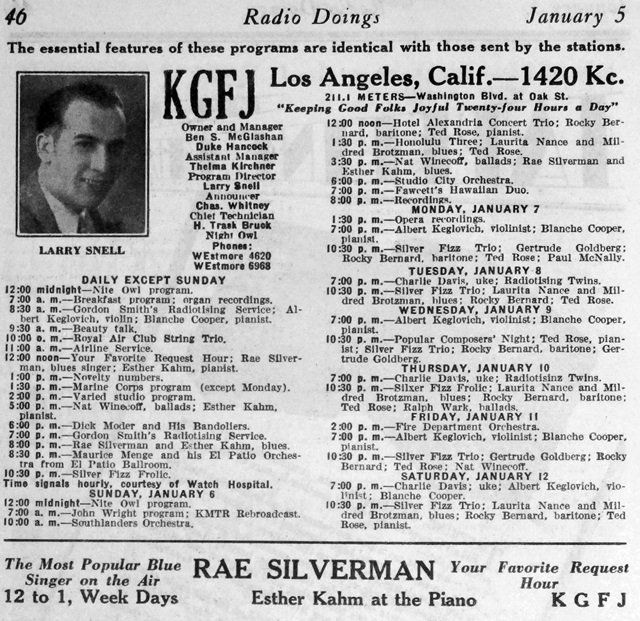

The KGFJ program schedule from Radio Doings, Jan. 5, 1929. larger image

The KGFJ program schedule from Radio Doings, Jan. 5, 1929. larger image

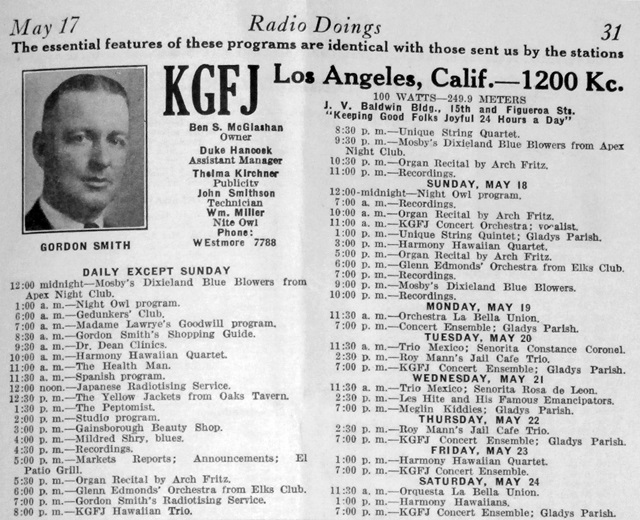

The KGFJ program schedule from Radio Doings, May 17, 1930. larger image

The KGFJ program schedule from Radio Doings, May 17, 1930. larger image

KGFJ’s Owner Gains Attention in Trade Magazines

In 1930, young McGlashan was well liked and

respected. A July 19, 1930, article in Radio Doings

titled “The 24-Hour Station” by early Los Angeles radio

engineering expert K.G. Ormiston, said that at one broadcaster's luncheon, the

manager of one of the bigger stations in L.A. was looking for a place to

sit. A friend suggested, "Sit by Bennie McGlashan. He might

tell you how to make a broadcast station pay!"

Another article in the March 1, 1932 issue of Broadcasting

said that 100-watt

KGFJ, in the heart of Los Angeles, was a major financial and musical

success. The station had its own 22-piece orchestra and a long list

of loyal advertisers. McGlashan said at the time he owed his success

to his "ten commandments" of business, which started with,

"Operate 24 hours a day." Some of his other rules included

"Cash in advance", and "Put money back into

programs." To read the entire article, click

here.

Late Night Radio Hobbyists Unhappy With KGFJ Schedule

KGFJ was easily heard in the 1930s by the

long-distance radio hobbyists known as DXers, who tuned across their radio

dials late at night or early in the pre-dawn hours to hear ID's from distant

radio stations. Since KGFJ was the only station on the 1200 channel

broadcasting during the wee small hours of the morning, its signal was heard by

an unknown numbers of far-away listeners, especially during the cold winter

months. But, many of the DXers also wrote letters to the popular radio

magazine of the day, RADEX or Radio Index.

They complained that KGFJ was hogging the 1200 kHz frequency all night.

They said the station was interfering with their chances of hearing other

stations on 1200 or adjacent channels of 1210, 1220, 1180 and 1190. Some

of the radio hobbyists said they should write letters of complaint to the FCC

about the situation.

In October 1934, RADEX published a letter from

Luther E. Grim, publicity manager of the National Radio Club. On a trip

out West from Pennsylvania, Grim visited KGFJ "to see why this station

refused to leave the air." He spoke with KGFJ’s program director,

Thelma Kirchner. Grim said, "Miss Kirchner of the station was rather

indignant that the DX fraternity should think so harshly of them. She

informed me that they have a sponsor for those early morning hours and

explained that every morning they missed, due to frequency checks, had to be

made up under their contract. KGFJ is by contract, duty bound to

broadcast all night. It made me wonder how many of us DXers would close down a

station if we were in Mr. McGlashan's position."

Thelma Kirchner (1904-1991) had been with KGFJ since 1927,

three months after the station first went on the air. She eventually

became general manager of KGFJ in 1942, and was possibly one of the first women

to hold that job at a radio station. She had that job title until the

station was sold in 1964. A story in the January 11, 1954 issue of

Broadcasting magazine profiled Kirchner and her years at KGFJ is

here.

I should explain here a bit about frequency checks. During the 1930s, the FCC

required the low-powered local stations to do monthly frequency check tests

after midnight for about 15 to 20 minutes. The tests were performed to

determine if a station was operating precisely on its assigned frequency.

The frequencies for these monthly tests were 1200, 1210, 1310, 1370, 1420 and

1500 kHz (after March 29, 1941, the local AM frequencies became 1230,

1240, 1340, 1400, 1450 and 1490). The radio hobbyists known as

DXers, who tried to hear distant stations late at night, would tune the band after

midnight and would often receive rare stations during these test periods

between midnight and 6 a.m. (Stations on the other frequencies, clear and

regional channels were also required to do frequency checks.)

In 1935, for example, there were 230 stations on those six local frequencies.

If a station in Georgia, Pennsylvania, Arkansas, Wisconsin, Minnesota,

Montana, or any other states with a station on 1200 kHz performed a

frequency check in 1935, the FCC required the other stations on 1200 to sign

off, which provided a clear channel shot for DXers to hear some distant,

low-powered stations. So, KGFJ-1200 in Los Angeles had to sign-off the

air during any 15-minute frequency check that took place in the

1930s. Since KGFJ had sponsors for its all-night programming, going

off the air for frequency checks meant making up commercials at a later

date.

Such a frequency check typically consisted of mostly band music and

marches. After every such record was played, the station identification

was given by the announcer or station engineer. By the 1970s, there were

very few such frequency checks given over the air. But, such tests by

that time did not always last 15 minutes. Also, they consisted of test

tones and few, if any, station IDs. Also by the 1970s, stations did not

have to leave the air for frequency checks, but the station performing the test

could use its full daytime transmitter power and if the station had directional

pattern only at night, the test could be performed using its non-directional

antenna pattern.

In the National Radio Club’s 50th Anniversary book from 1983,

a DXer named Carleton Lord who lived in Ohio in 1935 was quoted during the 1981

NRC convention about the “graveyard frequencies” such as 1200. He said

that during 1935, he had heard and verified 77 out of the 83 stations from

California, Oregon and Washington due to the band being so “open” for DXers

during the hours between midnight and 6 a.m. He had also heard and verified

211 out of 230 local channel stations in 1935/ Such a record was

impossible by the 1980s, with the band filled with thousands stations and so

many staying on the air all night.

Other All-Night Programming On KGFJ

As the Depression years of the 1930s progressed, Ben

McGlashan filled the KGFJ airwaves with other types of programming from

midnight to 6, beside just phonograph records, which made those overnight hours

profitable for him. He started playing syndicated sponsored transcriptions.

According to radio historian Elizabeth McLeod, this was sort of a

precursor to the use of infomercials as overnight paid filler programming on

cable television in recent years.

In fact, McLeod went on to tell me that much of

the KGFJ broadcast day at the time (1931-1934) was made up of records, paid

broadcasts by various ministers and fringe politicians, and 15, 30 or 60-minute

transcribed ads for weight loss scams, laxatives and other obscure

merchandise. Many of these KGFJ advertisers were occasionally mentioned

in a column in Broadcasting magazine entitled

"Station Accounts."

Despite this shady type of programming, which was also

heard on other L.A. stations from time to time in the 1930s, the fact that it

was the only station on the air around the clock attracted much attention and

made KGFJ very popular with nite-owls, overnight workers, insomniacs and

late-night DX enthusiasts. Letters reporting reception of KGFJ's signal

poured in from every part of the U.S.

More 1930s All-Night Broadcasting

Earlier in this article, I cited examples of all-night broadcasting, mainly in

the Los Angeles area, in 1929 and 1930. In December of 1931, RADEX

magazine published a letter from a DXer that said KELW in Burbank, California was

on the air from 1 a.m. to 6 a.m., dividing time on 780 kHz with KTM-Los Angeles.

KTM signed off the air at 1 a.m. and returned to the air

from 6 to 10 a.m. Meanwhile, KHJ in Los Angeles was on the air until 1

a.m., KMTR in Hollywood was still broadcasting until 3 a.m., while KFI was off

from midnight until 6:45 a.m.

By 1933 and ’34, the share-time agreement had been changed on 780-AM in L.A., with KTM on until 4 a.m. and KELW on from 4 a.m. to 6 a.m. One could

make an argument that this was a 24-hour broadcast, though technically they

were broadcasting with two different radio station licenses, with two different

transmitter locations, but dividing their air time on 780 kHz.

Also in 1933, the all-night radio scene had a new station popping up after

midnight, besides KGFJ. RADEX magazine reported that 50-watt WEXL

in Royal Oak, Michigan on 1310 kHz would start an overnight broadcast

schedule from 1:30 to 5:30 a.m. Eastern time. Also, KJBS in San Francisco, 100 watts on 1070 kHz, was staying on the air all night.

Earlier in this article, I wrote that KJBS began broadcasting between midnight

and 6 a.m. in April of 1930.

By March 8, 1935, KGFJ’s Night Owl Program from midnight to 6 a.m. had new

competition in Los Angeles, as KFAC-1300 went to a 24-hour a day schedule with

its “Kennel Club” program from midnight to 7 a.m. And on 780, KTM was

still on until 4 a.m. At that time, KELW-Burbank took over the 780 air

time from 4 to 6 a.m., broadcasting a popular Spanish language show that

started a couple of years earlier on KELW. That particular program on

KELW had been heard as far away as New Zealand.

Joining the world of all-night radio on Tuesday August 6, 1935, was WNEW-1250

kHz in New York City with the “Milkman’s Matinee” record show from 2 to

7 a.m. In 1938, WNEW promoted itself as serving New York and New Jersey 24 hours a day. In 1998, a book called "The Airwaves of New York” was

published. But apparently the writers didn't know about KGFJ starting the

practice of 24-hour broadcasting on the West Coast in 1927, or that KFAC was on

the air 24 hours a day, five months ahead of WNEW. Their book incorrectly

called WNEW "the first station to regularly remain on the air

twenty-four hours a day."

By 1938, KGFJ and KFAC were the only two Los Angeles radio

stations broadcasting 24 hours a day. However, KFAC took a two-hour

silent period on Wednesday mornings from 3 to 5 a.m., possibly for

maintenance. All the other L.A. stations at this time went off the air at

midnight or 1 a.m. The radio logs in the Los Angeles Times

showed that by June 1, 1938, KGFJ and KFAC were joined during the overnight

hours by KRKD with Midnight Express from midnight until 6 a.m., with KFVD

playing records until 4 a.m. with “Jack the Bellboy.” These three

stations continued with all night shows on L.A. radio through the end of 1939,

though KRKD-1120 was not on for 24 hours. It shared 1120 kHz with

KFSG at Angelus Temple, which was on the air weeknights from 7 pm to midnight

as well as Sunday services.

DXers Want All-Night Stations Silent After Midnight

Between 1935 and 1940, the letters from DXers in RADEX magazine

became more frequent with more complaints about stations staying on the air all

night. For instance, in 1935, letters complaining about stations staying

on the air all night were printed about KRE-1370 in Berkeley, California, along

with KGGC-San Francisco and KJBS-1070 in San Francisco. During 1936,

DXers were upset about not only KGFJ, KFAC and WNEW being on the air all night,

but they also reported that now they had to put up with WJBK-1500 in Detroit, Michigan going to a 24-hour schedule, plus WEXL-1500 broadcasting mostly all

night. By 1939, another Bay Area station, KLS at 1280 kHz in Oakland, California was added to the list of 24-hour stations. The 24-hour lineup of

all night music in Los Angeles stayed the same in 1940 on KGFJ, KFAC and KRKD

also on from midnight to 6.

KGFJ Takes On Other Projects

In 1928, KGFJ began broadcasting primitive television signals, using a mechanical spinning disc. This was likely the earliest television of any kind in the Los Angeles area. This TV station was on a wavelength of 62 meters, which is equivalent to 4835 kHz, and was on the air from 8 pm to midnight.

This early television experiment was the front page topic in the magazine “Sound Wave” from October 1, 1928. To read the story of KGFJ's entry into early televison, go to this link.

The magazine is from the Margaret Herrick Library Digital Collections, at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Another publication, Television Weekly News from April of 1931, featured KGFJ on the cover.

Another chart on early TV on the internet said that KGFJ was transmitting its TV signal between 2000 and 3000 kHz.

KGFJ apparently gave up on television soon after 1931, since nothing else is found regarding their TV experiments after that year.

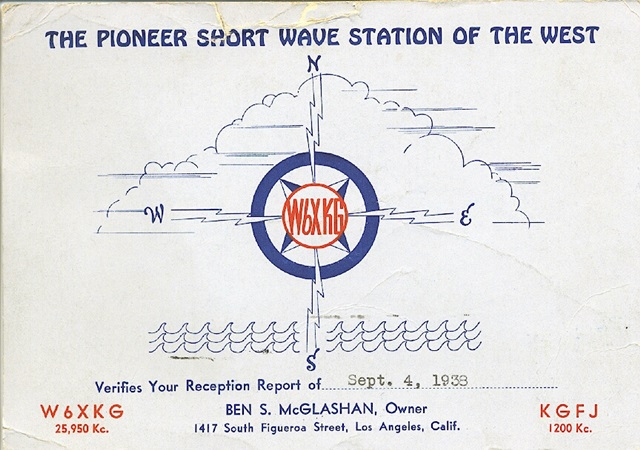

In 1936, KGFJ added a shortwave transmitter on 25.590 MHz to relay a shortwave station in Germany, which was covering the Summer Olympics in Berlin. When the Olympics ended, KGFJ used the shortwave station to simulcast KGFJ-1200 kHz until the early-1940s. The power of the station with the call sign of W6XKG was initially 100 watts, but was later increased to 1,000 watts.

A 1938 QSL card for W6XKG. Two QSL confirmation letters from 1937 are here and here.

Images courtesy of The Committee To Preserve Radio Verifications, which is associated with the Library of American Broadcasting, University of Maryland.

A 1938 QSL card for W6XKG. Two QSL confirmation letters from 1937 are here and here.

Images courtesy of The Committee To Preserve Radio Verifications, which is associated with the Library of American Broadcasting, University of Maryland.

Jerry Berg, who has written a series of books on shortwave history, says there were several of the “apex” shortwave stations during these years. Many moved to the new FM band, but KGFJ's did not.

Many years after Ben McGlashan sold KGFJ, the station was co-owned with KUTE-101.9 FM from the mid-1970s until 1987 (now KSCA).

World War II Puts More Stations on 24-Hour Schedule

The big increase in 24-hour broadcasting across the nation

took place when World War II started. With war-time factories going 24

hours a day, nearby radio stations saw the need to keep the workers

entertained and informed during their graveyard shifts.

Just before the United States entered World War II, this is

what was taking place on the radio in L.A. after midnight: On Friday

November 28, 1941, KGFJ was beginning its 15th year of broadcasting

from midnight to 6 in the morning. KFAC continued its 24-hour schedule

after nearly 7 years with “Night Melody Cruise” until 6 a.m. In addition,

KRKD was staying on the air until 3 a.m. with music in a program called “Monkey’s

Jamboree,” while KMPC entertained listeners until 3 a.m. with the “Milkman’s

Serenade” program. KNX and KHJ also had music programs on after midnight,

but only for an hour or two.

Following the December 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the all-night broadcasts in the Los Angeles area increased a

bit. In the radio schedule for December 22, 1941 in the Los Angeles

Times, KGFJ and KFAC were joined by KHJ and KFI with news and music until 6

a.m., while KRKD and KNX had music until 3 a.m. Fast forward to one year

later on December 7, 1942. and KGFJ, KFAC, KFI, KHJ, KNX and KMTR were staying

on the air for 24 hours each day.

By 1943, in Los Angeles, the 24-hour stations included KGFJ,

KFAC, KFI, KHJ, KNX and KMTR. In the Bay Area, KLS was not on all night

anymore, but KPO (now KNBR-680) and KGO in San Francisco went to a 24-hour a

day schedule during the war, and KJBS (now KFAX-1100) was on the air from 10 pm

until sunset the following day.

Across the United States during 1943, there was also a large

increase in the number of radio stations staying on the air past midnight until

6 a.m. The listing below was taken from the 1943 Radio Annual. In Washington D.C., WOL, the Mutual network station, was the only broadcaster on 24

hours. At least three radio stations in Florida were on the air 24 hours;

in Chicago, WIND, licensed to Gary, Indiana was on 24 hours. Other

stations on the air 24 hours a day that year included KFBI in Wichita, Kansas;

WHAS in Louisville, Kentucky; WNOE in New Orleans; WBAL and WITH in Baltimore,

WCCO and KSTP in Minneapolis, Minnesota; KXOK in St. Louis; WOW in Omaha,

Nebraska; WAAT in Jersey City-Newark, New Jersey; WKBW in Buffalo, New York;

and in New York City, WNEW was joined by the CBS network affiliate WABC-880

(now WCBS); WJZ-770 (now WABC), WOR-710 was 24 hours for 6 days a week and till

2 a.m. on Sundays; and WHAM-Rochester, New York. In North Carolina,

WPTF-Raleigh went to a 24-hour schedule. So did WJW-Akron, Ohio;

WLW-Cincinnati; KOIN-Portland, OR; KYW in Philadelphia ran a 24-hour-a-day

schedule four days out of seven each week; WIP in Philadelphia was on 24 hours

every day; WWSW in Pittsburgh was on daily 24 hours, while KDKA was

broadcasting 24 hours a day five days each week; in Seattle, WA, KJR and KIRO

were on for 24 hours each day.

By the end of the war in 1945, the same six Los Angeles stations that were on the air for 24 hours in 1943 were still on a 24-hour

schedule. Other California stations with 24-hour schedules were KMJ in

Fresno, KFBK-Sacramento; KLS-Oakland; KPO and KGO in San Francisco, while KJBS

was still on the air all-night from 10 pm until sunset the next day.

According to the 1945 Radio Annual, other 24-hour-a-day

radio stations during 1945 included WDBO-Orlando, Florida; WSUN-St. Petersburg,

Florida; WIND-Chicago; WHAS-Louisville, Kentucky; WDSU-New Orleans;

WITH-Baltimore; WJBK-Detroit, Michigan; WEXL-Royal Oaks, Michigan;

KSTP-St-Paul-Minneapolis, Minnesota; WAAT-Newark, New Jersey; WJZ-New York

City; WNEW-New York City; WOR-New York City; WLW-Cincinnati; WCOL-Columbus,

Ohio; KOIN-Portland, Oregon; WHAT-Philadelphia was on from midnight to 7 a.m.,

though it shared time with another station on 1340; WIP-Philadelphia;

WWSW-Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and WHBQ-Memphis.

For both 1943 and 1945, there were a large number of radio

stations where their ‘time on the air’ was listed in the Radio Annual only as

“unlimited time” or “unlimited license”, so it is impossible to determine how

many of those stations were actually broadcasting 24-hours a day. Many

other stations stayed on the air until 1, 2, 3 or even 4 a.m.

After World War II had ended, the 1946 Radio Annual

indicated that Los Angeles radio stations KFAC, KFI, KGFJ, (which had moved to

a new studio-office site at 6314 Sunset Blvd. in Hollywood), and KHJ were all

broadcasting 24 hours each day. In addition, KGER in Long Beach was now a

24-hour station along with KXLA-1110 in Pasadena. Other California

stations with 24-hour schedules included KMJ-Fresno, KWBR-Oakland,

KFBK-Sacramento, KGO-San Francisco, with KJBS in that city on only until 3 a.m.

Post-War 24-Hour Stations

According to the 1948 Radio Annual, KGFJ was still on the air 24 hours a day,

along with KFAC, KFI and KXLA-Pasadena. KHJ now signed off the air at 1

a.m., while KGER in Long Beach was now off by midnight. A new station in Burbank, KWIK-1490 stayed on the air until 3 a.m., but a new San Bernardino station,

KRNO-1240 was on 24 hours each day. Other California 24-hour radio

stations in 1948 included KMJ-Fresno, and KSON-San Diego.

In other states during 1948, these stations were reported on the air 24 hours a

day: KRUX-Glendale-Phoenix, Arizona; KFEL-Denver; WWDC-Washington, D.C.;

WBAY-Coral Gables, Florida; WBGE-Atlanta; WDSU-New Orleans; WNOE-New Orleans;

WITH-Baltimore; WJBK-Detroit; WJLB-Detroit; WJR-Detroit; WBBC-Flint, Michigan;

WEXL-Royal Oaks, Michigan; WAAT-Newark, New Jersey; WINS, WNEW and WOR,

all in New York City; WADC-Akron, Ohio; WLW-Cincinnati;

WING-Dayton, Ohio; and KALE in Portland, Oregon stayed on for 24 hours

Saturday night/Sunday morning.

Once again, there were a large number of stations listed as being on the air for “unlimited time,”

which makes it difficult to determine if those radio stations had a 24-hour schedule or not.

24-Hour Radio in the 1950s

By 1951, it is more difficult to tell who is on the air all-night or for 24

hours each day. In the Radio Annual of that year, some stations don’t

list their time on the air or list it as “unlimited,” and the Los Angeles Times

Radio Log shows only stations that are on at midnight, but it does not indicate

if those stations were on all night or only an hour or two past midnight.

I can tell that in Los Angeles, KGFJ and KFAC were still on the air 24 hours

each day, along with KXLA-1110 in Pasadena. KWKW-1300 in Pasadena is listed in the paper as on at midnight and may have been a 24-hour station.

KWKW also had an ad in the 1950 Radio Annual showing that it was on the

air 24 hours a day, so that was likely still the case. KFI and KFWB also

may have been on for 24 hours at the time, but I’m not positive. KECA was

showing “unlimited time” as their air time, but may not have been on for 24

hours. KFVD went off the air at 2 a.m., KNX at 1 a.m., and KMPC and KHJ

were off the air at midnight. Around the rest of the state, KMJ in Fresno was on 24 hours a day in 1951, as was KSON-San Diego, KXRX in San Jose, and KYA in San Francisco.

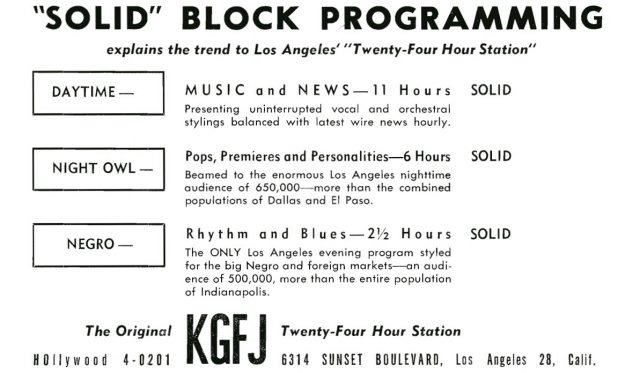

In this 1954 advertisement KGFJ is still promoted as the original 24-hour station.

In this 1954 advertisement KGFJ is still promoted as the original 24-hour station.

Why DXers Looked Forward to Monday Mornings

Retired broadcaster and chief engineer from the South Lake Tahoe, California/ Reno, Nevada area, Bill Kingman grew up in Pasadena. In an email to me,

he recalled that in the early-1950s, “The popular L.A. biggies like KNX, KMPC,

KFI, KLAC, KHJ, KECA, KFWB, KXLA (and KGFJ of course) were all operating 24

hours. But, all of them signed off the air at midnight on Sunday nights for

weekly maintenance until 5 or 6 a.m. on Monday. KFI (after midnight)

would sometimes play John Phillips Sousa marching band records during that

time, with the announcement, “Testing.” Bill added, “I recall in the

1960s that KNBC-680 (now KNBR) in San Francisco had no programming nightly

after midnight, but maintained a silent carrier all night at 50,000 watts with

hourly legal station IDs, because it was the primary CONELRAD station for

Northern California.” (The CONELRAD alert system was changed after 1963

to the Emergency Broadcast System and is now called the Emergency Alert System

or EAS)

During the 1930s, most station equipment tests or DX tests took place just

about any night of the week, with many scheduled for Friday night/Saturday

morning or Saturday night/Sunday morning. As Bill Kingman pointed out in

the paragraph above, by the 1950s, many of the 50,000 watt clear channel AM

stations across the United States went off the air at midnight for weekly

station equipment maintenance in the studio or at the transmitter. This

became a fairly common practice between midnight and 6 a.m. Monday morning,

since stations typically had the least amount of listeners on a late Sunday

night. With those stations off the air for several hours

once-a-week, DXers looked forward to possibly hearing AM stations on those

frequencies from outside the United States, or in some cases a daytimer on a

clear channel testing after midnight or signing on the air at sunrise. By

the 1960s and ‘70s, and even into the 1980s, the practice of stations going off

the air Monday mornings after midnight was common not only for clear channel

stations, but for many of the regional and local 24-hour stations.

Bill Kingman added another interesting comment about 24-hour radio stations

going off the air for several hours after midnight once a week for transmitter

and/or studio equipment repairs. He worked at KOWL-1490 in South Lake

Tahoe, California, which was a 24-hour-a-day station since it first went on the

air in 1956. Bill noted that KOWL chose a different night to

sign-off the air for weekly maintenance:

I was the all-night deejay on 24-hour KOWL (AM) 1490 in Lake Tahoe in 1961. The General Manager did not want KOWL to sign-off on Sunday nights for two reasons: (1) because he knew all other stations were off. Therefore, KOWL with only 250 watts on local channel 1490, essentially had a clear channel those early Monday mornings. As a result, I received DX reports and listener mail from New Zealand, Calgary, Mexico, San Diego, Los Angeles, and Finland! (2) Lake Tahoe is a tourist mecca, especially on weekends. That's also why he moved off-air weekly maintenance to Tuesday mornings, 12-6am, rather than on Monday mornings. Unless a station had a spare transmitter and studio, weekly maintenance was important in those all-tubes days.

Today, it is extremely rare to have an AM or FM station stop broadcasting for

overnight transmitter or studio work, or for any other reason. According

to a radio station chief engineer who wishes to remain anonymous, it is a very

important decision to schedule off-air time for any major market station.

The engineer went on to say that the situation has to be fairly dire before the

programming department or general manager will approve taking a station off the

air, because too much money is at stake. In closing, he said that newer

equipment used in radio stations today is far more reliable than earlier

technology, especially the transmitters and related equipment.

In the Los Angeles Times radio page for October 14, 1955, the schedule

at midnight shows KFI with “The Flyer” and then Ben Hunter at 1 a.m.; KNX had

“Music Till Dawn”; KABC aired “Rourke In Hollywood”; KFAC was on all night with

“Nite Music”; KLAC had news and music at midnight; KFWB offered “The Larry

Finley Show”; KXLA gave the listeners “Night Life”; KRKD was on with

“Serenade”; KMPC was “On ‘Til Dawn”; and KGFJ had “Nightclub.” The radio

listings for Chicago, New York City and Washington, D.C. show many of their

major stations also with 24-hour schedules, all-night shows, etc.

The 1960s and Beyond

In December of 1960, the Los Angeles Times Radio Log does not list every

station every hour. As for their midnight listing, the paper shows KNX,

KFI, KMPC, KFWB and KLAC with all-night shows. KFAC and KGFJ are not

listed, though they were on 24 hours. Also, KABC, KHJ, KRLA, KWKW

and a few others may have had 24-hour programming at the time.

In some markets, a need to stay on the air 24 hours was created. Such was

the case in 1964 in Salt Lake City. KSL radio’s Herb Jepko created his

overnight Nitecap talk show that year to fill the midnight to 6 a.m. hours,

when KSL had previously been off the air.

In smaller towns and cities, many stations still went off the air at midnight

into the 1970s and ‘80s. But, there was a significant increase in the number of

AM and FM stations across the United States that were broadcasting

24-hours-a-day by the 1970s. As automated satellite shows, both talk and

music, became more popular, it was more common for stations to stay on the air

all night without having a board operator. As computer automation

improved into the 1990s, the all-night disc jockey was out of a job in many

markets too, with all music with liners or with voice-tracked

announcements.

Ben McGlashan’s dream of owning a radio station in Los Angeles came true on

many levels. He worked hard to make it a financial success and a success

with the listeners. Much of that early success took place during a

time when a low-powered station in a big city didn't mean your message wouldn't

be heard, even up against radio stations with greater transmitter power

and resources. After 37 years, Ben McGlashan finally sold KGFJ for $1.5

million in August of 1964 to Tracy Broadcasting Company, owned by Richard B.

Stevens and Associates. The buyer also owned WFEC in Pennsylvania.

McGlashan retired to his home in Bel Air and died in 1976 at the age of

72.

During the last years of Ben McGlashan’s

ownership of 1230-AM, KGFJ programmed heavily for the African-American

population of Los Angeles, with Rhythm and Blues (R and B) music, along with

news and public affairs programming. Other music formats from the 1960s to the

1990s included classic soul and gospel music. A talk format was briefly heard

on KGFJ after the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Between October 1977 and October

1979, I pointed out earlier in this essay that the KGFJ calls were changed to

KKTT (“The Katt”), following the ratings success of KDAY-1580 (now KBLA), which

had a similar format as KGFJ.

In October of 1979, the call letters were

changed back to KGFJ and on May 1, 1996, the historic KGFJ calls became KYPA

(Your Personal Achievement), with a motivational talk format. The station

later was purchased by Multicultural Broadcasting. KYPA-1230 is now a leased-time

station with Korean-language programming, and is co-owned with KBLA-1580, a

Spanish-language station. As I wrote earlier in this article, the historic

1230-AM flattop wire antenna for KGFJ/KKTT/KGFJ/KYPA was last used by KYPA on

January 14, 2009. KYPA-1230 now transmits its signal from the KBLA-1580 tower

site in the Echo Park area of Los Angeles. To read more about the history of

the first KGFJ studio site and site of its transmitter/antenna from 1927-2009,

and see photos of the building, here’s the link to a very good article from

Scott Fybush’s site on radio station transmitter sites.

Veteran Los Angeles broadcaster Greg Hardison added a memory or two of KGFJ. He emailed me to say, “For many years, KGFJ-1230 was one of the finest Soul/R and B stations in the country. I especially enjoyed hearing their great R and B music in AM stereo, circa 1989-1991.”

The AM license for KYPA-1230 in Los Angeles, which first went on the air as KGFJ in 1927,

is the 9th oldest AM station license in the city of Los Angeles and the

12th oldest station license in the entire Los Angeles market, including Orange County.

We've come a long way from the sounds in the night of

the 1920s and the music that filled the air with the Big Bands all night

in the '40s. Many of you grew up with the sounds of your favorite all-night DJs

who brought you the hits of the day in the '60s and '70s and beyond. The

tradition continues today, with all night music, or continuous news and sports

talk programming, and various talk shows. And to think that regular

all-night broadcasting started at 100-watt KGFJ in November of 1927.

Acknowledgements and Sources

I want to thank radio historian Elizabeth McLeod for her

help in 2002, when I first began this project. She provided a lot of

valuable information on KGFJ’s legacy as a 24 hour station, when I wrote my

first article. I also want to thank media historian Donna Halper.

She sent me the 1930 Radio Doings article “The 24-Hour Station” by

Kenneth G. Ormiston, which also gave me important information for my 2002

article on KGFJ. I also included information on KGFJ and other 24-hour

radio stations from a few of my own copies of Radio Index or RADEX, mostly

from 1933 to 1935, and from my own copies of Radio Doings magazine from

1927 to 1930.

Now, more than 12 years later, there has been a remarkable

amount of information added to the Internet on radio history, which has made

research for this essay much easier than before. I found a lot of

details on the all-night stations from the J.J.’s radio logs website,

which listed radio program listings for Los Angeles, Chicago, New York City and

Washington D.C. from 1930 to 1960.

But the greatest source of information for this article came

from David Gleason’s superb Website American Radio History,

which is an online library of over a million pages of AM, FM and TV

broadcasting history. For my purposes, I used several issues of Radio

Index/RADEX magazine, Broadcasting magazine and Broadcasting Yearbook,

and the Radio Annual from 1938 to 1964. David has made these

publications searchable with an excellent search engine. I also found a

bit of information on KGFJ from a copy of Broadcast Weekly magazine from

1927 and from the Los Angeles Times historical database. The

National Radio Club’s 50th Anniversary book from 1983 was also a

source on the early years of AM band DXing. Information on KGFJ’s frequency,

call letter and transmitter power changes first came from the Department of

Commerce Radio Service Bulletins. Now, this information is conveniently found

on the FCC Website with the KGFJ history cards at

this link.

Finally, I want to thank Don Barrett for posting my first

version of this story on his LARadio.com Website in 2002, and to Jeff Miller

for his help in editing this article, and for posting the revised article on

his History of American Broadcasting Website.

Jim Hilliker

Monterey, CA

Jim Hilliker is a former radio broadcaster. He has researched and written about the early history of Los Angeles area radio for more than 20 years. Email: jimhilliker@sbcglobal.net.

|