Radio and the 1932

|

|

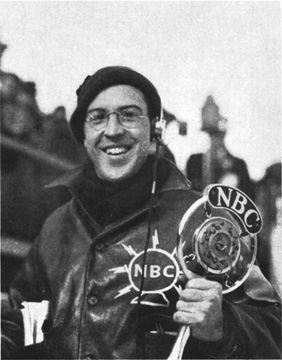

NBC special events announcer George Hicks (1905-1965), when he described the events at the 1932 Winter Olympics for NBC radio. He later was with NBC’s Blue Network and ABC, and was primarily a news reporter and commentator after 1941. |

I discovered that live broadcasts of the Olympics were not allowed from the Los Angeles games 80 years ago. This decision was made despite the fact that both NBC and CBS had been allowed to broadcast most of the events at the 1932 Winter Olympics from Lake Placid, New York, between February 4 and February 15, 1932. NBC used announcer George Hicks to call the action from nearly every venue, while CBS relied on their popular sportscaster Ted Husing (pictured at left). The Los Angeles Times radio listings each day indicate that NBC affiliate KFI and CBS affiliate KHJ aired the Winter Olympics coverage in Southern California.

|

Ted Husing (1901-1962), who also reported on the Winter Olympics for CBS in February of 1932. Husing was the top play-by-play sports broadcaster for CBS in the 1920s and ’30s. His opinions often got him into trouble. He was banned from announcing the World Series by the Commissioner of Baseball, because he criticized the umpires on the air during the 1934 World Series between the St. Louis Cardinals and the Detroit Tigers. |

In the March 13, 1932, Los Angeles Times radio column by William Hamilton Kline, he reported that Don Lee, owner of KHJ and the Don Lee Broadcasting System, had made a pitch in a letter to Zack J. Farmer, the general secretary of the Olympic Committee. Lee’s proposal was to broadcast “two hours of the most spectacular Olympic events” daily during the sixteen days of the games. The broadcasts were to be heard across the nation on 90 stations affiliated with the CBS and Don Lee networks, and via shortwave radio beamed overseas. But, apparently, the IOC and/or the Los Angeles Olympic Committee rejected any plan for live broadcasts of the games.

Why then was radio not allowed to broadcast live from the Summer Olympics that year? Apparently the organizers of the Los Angeles 1932 games were afraid that live radio broadcasts would keep paying customers away from the Coliseum and the other venues to witness the events in person, which would hurt ticket sales. This was the same reason many Major League baseball team owners in the 1930s refused to allow their games to be on the radio, as they argued that broadcasting the games would keep the fans away from the ballpark. Also, in March of 1932, some eastern universities such as Harvard and Yale decided that they would not allow any of their college football games to be broadcast on the radio that fall. So, it appears that the NBC and CBS live coverage of the 1932 Winter Olympics was an exception to the rule at that time. Another factor in not having the Los Angeles Summer Olympics broadcast live may have been pressure from newspapers, which also feared being “scooped” by radio during the 1930s, when it came to news and sports.

It wasn’t until the 1936 summer games in Berlin that live radio broadcasts of some of the events were heard in the USA at various intervals. The opening day ceremonies in 1936 were heard in Los Angeles at 8 a.m. Pacific Time via NBC on both KFI and KECA, while KHJ listeners heard the CBS network feed from Germany. Most of the regular events during the 1936 summer Olympics were heard mainly on KFI via NBC on Saturday and Sunday, and not as much on weekdays. Los Angeles Times sports reporter and columnist Bill Henry (1890-1970) also helped cover the 1936 Summer Games for CBS. When the Times owned KHJ between 1922 and 1927, Henry first went on the air at KHJ in 1922 announcing news and sports broadcasts, including college football during the 1920s and ’30s. Henry was also a sports technical advisor for the organizing Committee of the Xth Olympiad in Los Angeles, between 1928 and 1932.

Radio’s Role in the Los Angeles Summer Olympics

According to the 1932 Official Report on the Summer Games prepared by the Los Angeles organizing committee, it did briefly mention radio broadcasts:

A number of large radio advertisers built their programs around the Games. One series of broadcasts, given weekly, consisted of dramatizations of recreated past Olympiads beginning with the first Games of which there is record and moving swiftly to the Games of the modern era. Other programs featured the Olympic Games in music, talks by athletic experts and interviews by past Olympic champions.

The movie capitol of Hollywood also helped to promote the Los Angeles Olympics to potential tourists across the U.S.A. and around the word. On May 22, 1932 at noon Pacific Time, an international broadcast was made from the studios of the Don Lee-CBS network station, KHJ. The half-hour program over CBS and sent overseas by shortwave radio was Los Angeles’ official invitation to attend the Tenth Olympiad. Several movie stars such as Marlene Dietrich, Maureen O’Sullivan, Bela Lugosi, Jimmy Durante, Delores Del Rio, Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy took part. European listeners were invited to the Games in several languages. Another similar radio program was broadcast in July just before the start of the Games. It aired on July 7th at 8 pm over KECA and the NBC network from the Hollywood Bowl, the men’s Olympic Village and the Coliseum (Olympic Stadium). It was called “Come to the Olympics” and featured Douglas Fairbanks and his wife Mary Pickford, along with comedian Will Rogers.

When the time finally arrived for the Olympics to begin, Southern California radio fans would soon learn the plans that were made for radio to deal with the situation. KHJ at 900 on the radio dial had made a deal with the Los Angeles Times which would benefit both the radio station and the newspaper, and hopefully KHJ’s listeners too. Radio columnist Doug Douglas described the situation this way for his readers on July 29, 1932 in the Los Angeles Times:

The Times and KHJ have perfected the most complete official system yet devised to overcome the circumstance that no radio station is permitted to broadcast directly from the Coliseum or any of the other points at which Olympic events are to be held. Immediately following official announcement of the results, The Times Tower, over KHJ, will bring to your speaker the name of the winner, character of the event and the time.

While no live coverage was broadcast in 1932, it appears several other radio stations reported on the results at the Olympics each day, including KFI-640, KECA-1430, KFAC-1300 and KFWB-950. But Doug Douglas in the Los Angeles Times told his readers that KHJ was the best station to listen to for the latest news from the Olympics each day, from July 30 to August 14.

At 5 p.m. on July 30th, which was the opening day of the Olympics, KHJ was scheduled to broadcast a detailed explanation of the scoring system used at the Games. Douglas went on to write in his column that KHJ would broadcast official flashes every day detailing the progress of the various events. “In addition to the scheduled flashes, Braven Dyer, ace of the Times sports announcers, will bring a complete word picture of each day’s contests, with the scores worked out in the point system. Noted visiting sports writers will frequently give their version of the Games as they progress.”

The newspaper also printed their official Olympic broadcasting schedule for the first four days of the 10th Olympic Games. Besides the flash announcement of winners each day, KHJ was to broadcast results each day at 5 pm and 10 pm. On July 30th, after the 5 pm description of how to keep a day-by-day score in points of every event, the 10 pm broadcast featured Braven Dyer with a ten-minute eyewitness description of the opening ceremonies and the progress of the weight lifting contest, the first of the scheduled events. Douglas concluded his column that day this way: “Get your scorecard, cut out your schedule each day, dial KHJ and the Times Tower. In other words, if you haven’t a ticket, tune in.”

That day, the Times radio column headline proclaimed: “Olympic Inaugural Radio’s Peak. Games Opening Feature Today.” But there was no live radio broadcast of the Opening Ceremonies. KHJ featured Braven Dyer at 10 pm doing his best to give listeners a word picture of the opening ceremonies and events contested. Doug Douglas added that “Every day Don C. of the Times will flash over KHJ official results, as the events scheduled are concluded. Point the dial to KHJ and let ’er ride.”

I should add that John Braven Dyer (1900-1983) was a sportswriter and a sports columnist for the Los Angeles Times between 1925 and 1964. During some of those years, he was also heard on radio as a sportscaster or commentator, especially on early USC football games on radio in the 1920s and ’30s, and had his own sports show on KFI, KMPC and KNX between 1945 and 1960. Dyer is credited with creating the nickname “Thundering Herd” for the great USC football teams of the 1920s and ’30s.

Aside from what he wrote about the Olympics on July 29 and 30, Doug Douglas wrote very little about the games in his radio columns for the next two weeks. For instance, on August 2, 1932, all he put in the column that day was this: “Going to the Olympic Games? If you cannot, listen to Don C., intermittently throughout the events (KHJ), and fold up with Braven Dyer’s review of each day’s contests. KHJ at 10 p.m.” We never do learn what the C stands for in Don’s last name. The Times and KHJ also teamed up each day to present world-wide news on the radio station each day at 7:15 a.m., 12:30, 5:15 and 10:10 p.m.

In another column, Douglas says a reader wrote in to ask what to do about a neighbor who leaves their radio on all day. He replies that they should persuade them to enter the radio in the Olympic Marathon. On August 11, his radio column features a 1 p.m. broadcast on KHJ of “The Times Forum” on “The Drama of the Olympiad.” Douglas wrote that John Scott, a member of the Times staff would “relate some of the heart-breaking tremolo touches of the grueling contests. There are tragedies at the tape and in the locker rooms quite unobserved by even the most wide awake Olympic fan.”

Other Radio Coverage of the Games

The daily radio program log in the newspaper did not change much from day to day, when it came to listing anything to do with the Olympics. For instance, on Saturday August 6, KFI carried an NBC program called The Olympian; KECA presented Olympic news at 8 p.m.; KFAC did the same at 9 p.m.; KHJ at 10 p.m. and KFI’s Olympic news report was at midnight. On August 7, KHJ aired an Olympic summary at 10:30 a.m and noon; KFI was broadcasting a program that was heard over at least part of the NBC network at 2 p.m. called The International Goodwill Special, in which representatives of 20 nations taking part in the Olympics were scheduled to be on the program; KHJ presented another Olympic summary at 3 p.m.; KECA had Olympic news at 8 p.m.; KHJ’s Olympic summary of the day’s events with Braven Dyer aired at 10 p.m. and KFI had Olympic news at midnight.

During most of the Olympics, KHJ aired their regular reports on the games three or four times a day, along with their frequent “flashes” of the results of various events as those concluded. KECA, KFAC and KFI also were listed, though KFI’s report on the Olympics was only at midnight, except for one night when it was broadcast at 11 p.m. KFWB was listed only a few times with Olympic news.

There doesn’t seem to be any special broadcast for the final day of the games on August 14, 1932. KFI did air one more NBC broadcast on the games at 8 p.m., listed in the paper as the “Olympic Officials Special.” KHJ aired its final report on the Olympics at 10 that night and KFI at midnight.

I also checked radio listings in New York City during the games. Two stations did much the same thing as the L.A. stations. WABC (now WCBS-880) presented a report on the day’s events at the games each night from 11 to 11:15 p.m., and WJZ (now WABC-770) did the same thing at midnight. The same thing was done in Washington, D.C. The NBC affiliate WRC aired a 15-minute summary of the Olympics each night, usually at 11 p.m., while the CBS station WMAL, presented a summary of the games each day at 10:30 p.m., which also lasted for 15 minutes.

KFI’s Special Part in the 1932 Olympics

The two weeks that KFI presented Olympic news at midnight deserves some special attention here. It was a broadcast conducted by a Hollywood movie actress from New Zealand named Nola Luxford (1895-1994). The broadcast was created to deliver results of the summer games, mainly for listeners in New Zealand and Australia, focusing on how the athletes from those two countries did at the Olympics each day.

Miss Luxford’s story of how she became a radio announcer for KFI in the summer of 1932 is told in her biography published in 2000. It is titled Angel of the Anzacs: The Life of Nola Luxford by Carole Van Grondelle.

Sometime before the Olympics began, KFI had received letters from the New Zealand Athletics Association and the New Zealand Broadcasting Board. They asked if KFI could arrange daily broadcasts of the results of the Olympics involving the team from their country. This way, New Zealand would not have to wait a day or two for the results to appear in the newspaper. With KFI’s power increase to 50,000 watts the previous year, they explained that KFI’s night sky wave signal was often heard in July, during the colder New Zealand nights, where it was winter down under.

A KFI representative called Luxford and asked her if she knew of a man from New Zealand who could do the job. Nola thought that she could handle the job as well as any man. She drove to KFI the next day, where station manager Carl Haverlin introduced her to program director Glenn Dolberg. (Dolberg later became Luxford’s third husband in 1959) In later years, Carl Haverlin left KFI to become President of Broadcast Music Incorporated (BMI). Glenn Dolberg also moved on to BMI as Vice-President of Station Relations in the 1950s.

|

Glenn Dolberg, taken when he was with KHJ in 1930. As program director of KFI in 1932, he hired Nola Luxford to re-create the 1932 Summer Olympics on KFI at midnight for two weeks. The broadcasts were for New Zealand and Australia. In later years, Dolberg would follow his former KFI boss Carl Haverlin and go to work for Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI) as Vice-President in charge of Station Relations. |

She explained her idea of going on the air each night at midnight, when it would be 8 pm the next evening in New Zealand. Dolberg looked at her skeptically and said, “Whoever heard of a girl broadcasting sports events?” She replied confidently that she was certain she could do it, if KFI would give her the chance. Dolberg said he would think it over and let her know. A few days later, he telephoned her and said the station would give here a ‘try’.

At the time, it was felt that unless a woman was giving household hints, or worked as an actress or a singer on a radio program, the public did not wish to hear a woman’s voice on the radio. Some radio engineers argued that a woman’s voice was too high-pitched and above the audio frequencies of radio reproduction. This type of thinking is why in most cases, few women were heard on the radio in this country until well into the 1970s.

In Van Grondelle’s book on Luxford, she writes that Dolberg likely gave Nola the KFI job because he could tell she had the trained voice of an actress, but with a lower register that would be pleasing to the ear on the AM radios of the day. The program director was also taken by what the writer called Nola’s “intelligent and spirited personality, which he felt would project well over the air.”

An estimated 500,000 people were in Los Angeles for the next two weeks, which added to the city’s nearly 1.5 million population. Van Grondelle, who interviewed Luxford for her book and had access to her diaries, photos, etc., found that part of her first KFI script had been found from the Opening Day of the Summer Games. This is how Luxford described the scene to KFI listeners, many hours after it had ended:

It is a gorgeous day, Sunday, the 31st of July, 1932. (The opening ceremonies took place on the 30th in Los Angeles, but it was the next day for her target audience in New Zealand and Australia.) We are in this huge stadium, surrounded by one hundred and five thousand cheering, excited people, and the Parade of Nations, with two thousand of the world’s greatest athletes, assembled to take the Oath of the Olympiad. It is one of those days when one’s soul seems to be stirred to its very depths.

As for how she prepared for each night’s broadcast, Nola was busy from morning until afternoon, going from one Olympic venue to the next with her press pass. She would then go back to her apartment to write her script at the end of the day. Late at night, she drove to KFI to take her place before the microphone. KFI apparently could not give Nola a producer. But she had two engineers who helped mix her microphone and gave her some basic sound effects of the roar of the crowd and the crowd’s applause. When the broadcast was over, she returned home and was up early the next day to start over again.

To re-create each day’s events, she used the present tense and described each event as if they were happening as she spoke to the listeners. She not only focused on the New Zealand athletes, but tried to give an overview of every event each day, and the human interest stories surrounding all of the athletes. One of her popular features was her nightly sign-off, “Good night, mother dear.” Van Grondelle wrote that it was as if Nola was talking to all mothers, as she saluted her own in New Zealand.

Her favorite moment described in the book was when she watched the rowing competition from the Goodyear blimp in Long Beach. In one race, four crews were within one boat length at the finish, as the USA finally beat the Italians by a very thin margin. In describing the end of the race, Nola said, “We feel as exhausted as the young men slumped over their oars.”

When it all came to an end, Nola described the Closing Ceremony for KFI listeners this way:

The trumpeters play Taps, the torch goes out, the Olympic flag slowly comes down, as the sun is setting over the Pacific. The Olympic Games are over. Tears stream down the faces of many of the spectators. It is a solemn moment, as though we have lost a dear friend. The Olympic Games have passed into history.

The author wrote that Glenn Dolberg had fired Nola because NBC had given him a hard time about hiring her. But when thousands of cards, letters and telegrams flooded in from around the Pacific to praise Nola on her descriptions of the games and congratulate KFI for putting her on the air, she was given her job back. The total was later given as around 50,000 letters from Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, and from California to New York and Canada.

Nola Luxford spent the next four years at KFI as a freelance radio producer, presenter and Mistress of Ceremonies. From 1932 to 1936, she had organized some 20 special international goodwill broadcasts for Christmas, Easter, and Armistice Day. She presented all the programs herself. With her Hollywood film connections, she was able to get movie stars to take part, along with famous writers, musicians, plus many well-known bands, orchestras and choirs.

In 1936, Luxford moved to New York City and was part of NBC’s short-lived “Four Star News” program in 1939. The Four Star News was designed to give listeners a round-up of the week’s main news events, plus any late-breaking news that day. This news program lasted only 13 weeks until mid-November of 1939, but was not renewed by NBC.

During World War II, Nola formed the Anzac Club in New York (for Australia-New Zealand Army Corps) for soldiers from her country. She helped to make shortwave broadcasts of soldiers’ personal messages to relatives in New Zealand. Miss Luxford’s wartime efforts earned her the Order of the British Empire from King George VI and the U.S. Award of Merit from President Harry S. Truman.

Nola married former KFI program director Glenn Dolberg in 1959. He died in 1977. She spent her last decades in La Canada Flintridge, where Glenola Park is named in the couple’s honor. Miss Luxford died in Pasadena in 1994.

Some Final Thoughts

The world has changed so much in the 80 years since the Olympics were held in Los Angeles in 1932. Radio was only in its 10th year of regular broadcasting in Southern California. There were 17 radio stations in the Los Angeles region and 604 stations in the United States. Network radio was still evolving and adding new radio shows in 1932, which featured many vaudeville stars who were trying out the medium. Those included Al Jolson, Burns and Allen, Fred Allen, Jack Benny and Ed Wynn. Other new national shows on network radio were Buck Rogers, The Adventures of Charlie Chan, One Man’s Family, Tarzan, Vic and Sade and The Shadow. Singers and band music also filled the airwaves.

The Great Depression had brought the price of a radio in the U.S.A. down from $139 in 1929 to roughly $47 by 1933. But radio was a form of entertainment people wanted, despite their struggles to pay rent and buy food for their families. By 1929, about 33% of U.S. homes owned a radio and by 1933, that figure was close to 60%. In addition to that, radios were improving in quality and gave listeners better reception. It was estimated that by 1933, 4.5 million radios would become obsolete. Radio sales in the early-1930s increased due to “installment buying” or buying on credit. In 1931, 75% of all radios were sold on installment payments. The average down payment for a radio was 20%. But many in the United States could not find a job when the Olympics came to Los Angeles and could not afford to buy a radio. The unemployment rate in August of 1932 was 25%, the highest it had reached during the Depression.

Not only is radio different today, but the entire world of communications has changed drastically in the past 30 years. For the games this summer in London, there’s global television coverage by satellite, which could only be dreamed of in 1932. The home broadcaster, the BBC in Britain, will broadcast all 5,000 hours of the games through various channels. In the United States, NBC paid $1.181 billion to carry the games. NBC will also partner with YouTube to provide a livestream of the events. The summer Olympics will be seen and heard around the world.

As for radio, the 2012 Olympics will still be heard on radio through Fox Sports Radio over KLAC-570 in Los Angeles and the ESPN network over KSPN-710 in L.A. Olympic results will also be presented on KNX-1070 during regular sports segments.

Both the Olympics and radio would go through many changes over the decades. The United States and the world were so different in 1932 and today. The same goes for radio, and television in most homes was still a dream of the distant future to most Americans in 1932. I hope I have been able to describe at least some of what radio tried to do in 1932, when it came to promoting and reporting on the events of the Los Angeles Summer Olympics.

Main Sources Used

I would like to thank the LA ’84 Foundation for providing me access to the digital archives of their sports library. From their collection, I gathered information from the Spring-1997 Journal of Olympic History article “Radio Sports Broadcasting in the United States and Its Influence on the Olympic Games” by John McCoy, page 22. I also found some useful information in Volume XI-2002 of Olympika-The International Journal of Olympic Studies from page 87 of an article by Jeremy White entitled “The Los Angeles Way of Doing Things—The Olympic Village and the Practice of Boosterism in 1932.”

The LA ’84 Foundation Website also was the source for the photo of NBC radio reporter George Hicks and some information about the broadcasts of the 1932 Winter Olympics. Another item from their site which helped in my article was the Xth Olympiad Los Angeles 1932 Official Report. I also took information from the Los Angeles Times radio columns of February 4-15, 1932; March 13, 1932; May 22, 1932; July 7, 1932; July 29 and 30, 1932; and the radio program listings from the Los Angeles Times of May 23, 1932; July 7, 1932; and July 30 through August 15, 1932.

I found the material on KFI’s part in the 1932 Los Angeles Summer Olympics while doing a random search on the internet. This was all taken from a book on an actress from New Zealand who had arrived in Hollywood during the silent movie era. The book is Angel of the Anzacs: The Life of Nola Luxford by Carole Van Grondelle, and it was published in 2000.

Any comments, questions or corrections may be sent to the author, Jim Hilliker at jimhilliker@sbcglobal.net

Jim Hilliker

Monterey, CA

August 5, 2012