Radio’s War of the Worlds Broadcast (1938)

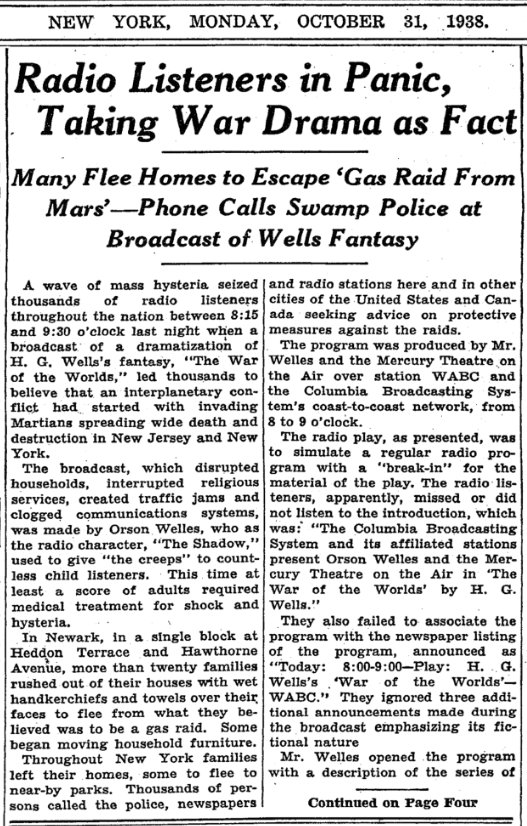

Radio Listeners in Panic, Taking War Drama as FactMany Flee Homes to Escape 'Gas Raid From Mars'—Phone Calls Swamp Police at Broadcast of Wells FantasyThis article appeared in the New York Times on Oct. 31, 1938.A wave of mass hysteria seized thousands of radio listeners between 8:15 and 9:30 o'clock last night when a broadcast of a dramatization of H. G. Wells's fantasy, "The War of the Worlds," led thousands to believe that an interplanetary conflict had started with invading Martians spreading wide death and destruction in New Jersey and New York. The broadcast, which disrupted households, interrupted religious services, created traffic jams and clogged communications systems, was made by Orson Welles, who as the radio character, "The Shadow," used to give "the creeps" to countless child listeners. This time at least a score of adults required medical treatment for shock and hysteria. In Newark, in a single block at Heddon Terrace and Hawthorne Avenue, more than twenty families rushed out of their houses with wet handkerchiefs and towels over their faces to flee from what they believed was to be a gas raid. Some began moving household furniture. Throughout New York families left their homes, some to flee to near-by parks. Thousands of persons called the police, newspapers and radio stations here and in other cities of the United States and Canada seeking advice on protective measures against the raids. The program was produced by Mr. Welles and the Mercury Theatre on the Air over station WABC and the Columbia Broadcasting System's coast-to-coast network, from 8 to 9 o'clock. The radio play, as presented, was to simulate a regular radio program with a "break-in" for the material of the play. The radio listeners, apparently, missed or did not listen to the introduction, which was: "The Columbia Broadcasting System and its affiliated stations present Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre on the Air in 'The War of the Worlds' by H. G. Wells." They also failed to associate the program with the newspaper listening of the program, announced as "Today: 8:00-9:00—Play: H. G. Wells's 'War of the Worlds'—WABC." They ignored three additional announcements made during the broadcast emphasizing its fictional nature. Mr. Welles opened the program with a description of the series of which it is a part. The simulated program began. A weather report was given, prosaically. An announcer remarked that the program would be continued from a hotel, with dance music. For a few moments a dance program was given in the usual manner. Then there was a "break-in" with a "flash" about a professor at an observatory noting a series of gas explosions on the planet Mars. News bulletins and scene broadcasts followed, reporting, with the technique in which the radio had reported actual events, the landing of a "meteor" near Princeton N. J., "killing" 1,500 persons, the discovery that the "meteor" was a "metal cylinder" containing strange creatures from Mars armed with "death rays" to open hostilities against the inhabitants of the earth. Despite the fantastic nature of the reported "occurrences," the program, coming after the recent war scare in Europe and a period in which the radio frequently had interrupted regularly scheduled programs to report developments in the Czechoslovak situation, caused fright and panic throughout the area of the broadcast. Telephone lines were tied up with calls from listeners or persons who had heard of the broadcasts. Many sought first to verify the reports. But large numbers, obviously in a state of terror, asked how they could follow the broadcast's advice and flee from the city, whether they would be safer in the "gas raid" in the cellar or on the roof, how they could safeguard their children, and many of the questions which had been worrying residents of London and Paris during the tense days before the Munich agreement. So many calls came to newspapers and so many newspapers found it advisable to check on the reports despite their fantastic content that The Associated Press sent out the following at 8:48 P. M.: "Note to Editors: Queries to newspapers from radio listeners throughout the United States tonight, regarding a reported meteor fall which killed a number of New Jerseyites, are the result of a studio dramatization. The A. P." Similarly police teletype systems carried notices to all stationhouses, and police short-wave radio stations notified police radio cars that the event was imaginary. Message From the Police The New York police sent out the following: "To all receivers: Station WABC informs us that the broadcast just concluded over that station was a dramatization of a play. No cause for alarm." The New Jersey State Police teletyped the following: "Note to all receivers—WABC broadcast as drama re this section being attacked by residents of Mars. Imaginary affair." From one New York theatre a manager reported that a throng of playgoers had rushed from his theatre as a result of the broadcast. He said that the wives of two men in the audience, having heard the broadcast, called the theatre and insisted that their husbands be paged. This spread the "news" to others in the audience. The switchboard of The New York Times was overwhelmed by the calls. A total of 875 were received. One man who called from Dayton, Ohio, asked, "What time will it be the end of the world?" A caller from the suburbs said he had had a houseful of guests and all had rushed out to the yard for safety. Warren Dean, a member of the American Legion living in Manhattan, who telephoned to verify the "reports," expressed indignation which was typical of that of many callers. "I've heard a lot of radio programs, but I've never heard anything as rotten as that," Mr. Dean said. "It was too realistic for comfort. They broke into a dance program with a news flash. Everybody in my house was agitated by the news. It went on just like press radio news." At 9 o'clock a woman walked into the West Forty-seventh Street police station dragging two children, all carrying extra clothing. She said she was ready to leave the city. Police persuaded her to stay. A garbled version of the reports reached the Dixie Bus terminal, causing officials there to prepare to change their schedule on confirmation of "news" of an accident at Princeton on their New Jersey route. Miss Dorothy Brown at the terminal sought verification, however, when the caller refused to talk with the dispatcher, explaining to here that "the world is coming to an end and I have a lot to do." Harlem Shaken By the "News" Harlem was shaken by the "news." Thirty men and women rushed into the West 123d Street police station and twelve into the West 135th Street station saying they had their household goods packed and were all ready to leave Harlem if the police would tell them where to go to be "evacuated." One man insisted he had heard "the President's voice" over the radio advising all citizens to leave the cities. The parlor churches in the Negro district, congregations of the smaller sects meeting on the ground floors of brownstone houses, took the "news" in stride as less faithful parishioners rushed in with it, seeking spiritual consolation. Evening services became "end of the world" prayer meetings in some. One man ran into the Wadsworth Avenue Police Station in Washington Heights, white with terror, crossing the Hudson River and asking what he should do. A man came in to the West 152d Street Station, seeking traffic directions. The broadcast became a rumor that spread through the district and many persons stood on street corners hoping for a sight of the "battle" in the skies. In Queens the principal question asked of the switchboard operators at Police Headquarters was whether "the wave of poison gas will reach as far as Queens." Many said they were all packed up and ready to leave Queens when told to do so. Samuel Tishman of 100 Riverside Drive was one of the multitude that fled into the street after hearing part of the program. He declared that hundreds of persons evacuated their homes fearing that the "city was being bombed." "I came home at 9:15 P.M. just in time to receive a telephone call from my nephew who was frantic with fear. He told me the city was about to be bombed from the air and advised me to get out of the building at once. I turned on the radio and heard the broadcast which corroborated what my nephew had said, grabbed my hat and coat and a few personal belongings and ran to the elevator. When I got to the street there were hundreds of people milling around in panic. Most of us ran toward Broadway and it was not until we stopped taxi drivers who had heard the entire broadcast on their radios that we knew what it was all about. It was the most asinine stunt I ever heard of." "I heard that broadcast and almost had a heart attack," said Louis Winkler of 1,322 Clay Avenue, the Bronx. "I didn’t tune it in until the program was half over, but when I heard the names and titles of Federal, State and municipal officials and when the 'Secretary of the Interior' was introduced, I was convinced it was the McCoy. I ran out into the street with scores of others, and found people running in all directions. The whole thing came over as a news broadcast and in my mind it was a pretty crummy thing to do." The Telegraph Bureau switchboard at police headquarters in Manhattan, operated by thirteen men, was so swamped with calls from apprehensive citizens inquiring about the broadcast that police business was seriously interfered with. Headquarters, unable to reach the radio station by telephone, sent a radio patrol car there to ascertain the reason for the reaction to the program. When the explanation was given, a police message was sent to all precincts in the five boroughs advising the commands of the cause. "They're Bombing New Jersey!" Patrolman John Morrison was on duty at the switchboard in the Bronx Police Headquarters when, as he afterward expressed it, all the lines became busy at once. Among the first who answered was a man who informed him: "They're bombing New Jersey!" "How do you know?" Patrolman Morrison inquired. "I heard it on the radio," the voice at the other end of the wire replied. "Then I went to the roof and I could see the smoke from the bombs, drifting over toward New York. What shall I do?" The patrolman calmed the caller as well as he could, then answered other inquiries from persons who wanted to know whether the reports of a bombardment were true, and if so where they should take refuge. At Brooklyn police headquarters, eight men assigned to the monitor switchboard estimated that they had answered more than 800 inquiries from persons who had been alarmed by the broadcast. A number of these, the police said, came from motorists who had heard the program over their car radios and were alarmed both for themselves and for persons at their homes. Also, the Brooklyn police reported, a preponderance of the calls seemed to come from women. The National Broadcasting Company reported that men stationed at the WJZ transmitting station at Bound Brook, N. J., had received dozens of calls from residents of that area. The transmitting station communicated with New York an passed the information that there was no cause for alarm to the persons who inquired later. Meanwhile the New York telephone operators of the company found their switchboards swamped with incoming demands for information, although the NBC system had no part in the program. Record Westchester Calls The State, county, parkway and local police in Westchester Counter were swamped also with calls from terrified residents. Of the local police departments, Mount Vernon, White Plains, Mount Kisco, Yonkers and Tarrytown received most of the inquiries. At first the authorities thought they were being made the victims of a practical joke, but when the calls persisted and increased in volume they began to make inquiries. The New York Telephone Company reported that it had never handled so many calls in one hour in years in Westchester. One man called the Mount Vernon Police Headquarters to find out "where the forty policemen were killed"; another said he brother was ill in bed listening to the broadcast and when he heard the reports he got into an automobile and "disappeared." "I'm nearly crazy!" the caller exclaimed. Because some of the inmates took the catastrophic reports seriously as they came over the radio, some of the hospitals and the county penitentiary ordered that the radios be turned off. Thousands of calls came in to Newark Police Headquarters. These were not only from the terrorstricken. Hundreds of physicians and nurses, believing the reports to be true, called to volunteer their services to aid the "injured." City officials also called in to make "emergency" arrangements for the population. Radio cars were stopped by the panicky throughout that city. Jersey City police headquarters received similar calls. One woman asked detective Timothy Grooty, on duty there, "Shall I close my windows?" A man asked, "Have the police any extra gas masks?" Many of the callers, on being assured the reports were fiction, queried again and again, uncertain in whom to believe. Scores of persons in lower Newark Avenue, Jersey City, left their homes and stood fearfully in the street, looking with apprehension toward the sky. A radio car was dispatched there to reassure them. The incident at Hedden Terrace and Hawthorne Avenue, in Newark, one of the most dramatic in the area, caused a tie-up in traffic for blocks around. the more than twenty families there apparently believed the "gas attack" had started, and so reported to the police. An ambulance, three radio cars and a police emergency squad of eight men were sent to the scene with full inhalator apparatus. They found the families with wet cloths on faces contorted with hysteria. The police calmed them, halted the those who were attempting to move their furniture on their cars and after a time were able to clear the traffic snarl. At St. Michael's Hospital, High Street and Central Avenue, in the heart of the Newark industrial district, fifteen men and women were treated for shock and hysteria. In some cases it was necessary to give sedatives, and nurses and physicians sat down and talked with the more seriously affected. While this was going on, three persons with children under treatment in the institution telephoned that they were taking them out and leaving the city, but their fears were calmed when hospital authorities explained what had happened. A flickering of electric lights in Bergen County from about 6:15 to 6:30 last evening provided a build-up for the terror that was to ensue when the radio broadcast started. Without going out entirely, the lights dimmed and brightened alternately and radio reception was also affected. The Public Service Gas and Electric Company was mystified by the behavior of the lights, declaring there was nothing wrong at their power plants or in their distributing system. A spokesman for the service department said a call was made to Newark and the same situation was reported. He believed, he said, that the condition was general throughout the State. The New Jersey Bell Telephone Company reported that every central office in the State was flooded with calls for more than an hour and the company did not have time to summon emergency operators to relieve the congestion. Hardest hit was the Trenton toll office, which handled calls from all over the East. One of the radio reports, the statement about the mobilization of 7,000 national guardsmen in New Jersey, caused the armories of the Sussex and Essex troops to be swamped with calls from officers and men seeking information about the mobilization place. Prayers for Deliverance In Caldwell, N. J., an excited parishioner ran into the First Baptist Church during evening services and shouted that a meteor had fallen, showering death and destruction, and that North Jersey was threatened. The Rev. Thomas Thomas, the pastor quieted the congregation and all prayed for deliverance from the "catastrophe." East Orange police headquarters received more than 200 calls from persons who wanted to know what to do to escape the "gas." Unaware of the broadcast, the switchboard operator tried to telephone Newark, but was unable to get the call through because the switchboard at Newark headquarters was tied up. The mystery was not cleared up until a teletype explanation had been received from Trenton. More than 100 calls were received at Maplewood police headquarters and during the excitement two families of motorists, residents of New York City, arrived at the station to inquire how they were to get back to their homes now that the Pulaski Skyway had been blown up. The women and children were crying and it took some time for the police to convince them that the catastrophe was fictitious. Many persons who called Maplewood said their neighbors were packing their possessions and preparing to leave for the country. In Orange, N. J., an unidentified man rushed into the lobby of the Lido Theatre, a neighborhood motion picture house, with the intention of "warning" the audience that a meteor had fallen on Raymond Boulevard, Newark, and was spreading poisonous gases. Skeptical, Al Hochberg, manager of the theatre, prevented the man from entering the auditorium of the theatre and then called the police. He was informed that the radio broadcast was responsible for the man's alarm. Emanuel Priola, bartender of a tavern at 442 Valley Road, West Orange, closed the place, sending away six customers, in the middle of the broadcast to "rescue" his wife and two children. "At first I thought it was a lot of Buck Rogers stuff, but when a friend telephoned me that general orders had been issued to evacuate every one from the metropolitan area I put the customers out, closed the place and started to drive home," he said. William H. Decker of 20 Aubrey Road, Montclair, N. J., denounced the broadcast as "a disgrace" and "an outrage," which he said had frightened hundreds of residents in his community, including children. He said he knew of one woman who ran into the street with her two children and asked for the help of neighbors in saving them. "We were sitting in the living room casually listening to the radio," he said, "when we heard reports of a meteor falling near New Brunswick and reports that gas was spreading. Then there was an announcement of the Secretary of Interior from Washington who spoke of the happening as a major disaster. It was the worst thing I ever heard over the air." Columbia Explains Broadcast The Columbia Broadcasting System issued a statement saying that the adaptation of Mr. Wells's novel which was broadcast "followed the original closely, but to make the imaginary details more interesting to American listeners the adapter, Orson Welles, substituted an American locale for the English scenes of the story." Pointing out that the fictional character of the broadcast had been announced four times and had been previously publicized, it continued: "Nevertheless, the program apparently was produced with such vividness that some listeners who may have heard only fragments thought the broadcast was fact, not fiction. Hundreds of telephone calls reaching CBS stations, city authorities, newspaper offices and police headquarters in various cities testified to the mistaken belief. "Naturally, it was neither Columbia's nor the Mercury Theatre's intention to mislead any one, and when it became evident that a part of the audience had been disturbed by the performance five announcements were read over the network later in the evening to reassure those listeners." Expressing profound regret that his dramatic efforts should cause such consternation, Mr. Welles said: "I don’t think we will choose anything like this again." He hesitated about presenting it, he disclosed, because "it was our thought that perhaps people might be bored or annoyed at hearing a tale so improbable."

Scare Is NationwideBroadcast Spreads Fear In New England, the South and WestLast night's radio "war scare" shocked thousands of men, women and children in the big cities throughout the country. Newspaper offices, police stations and radio stations were besieged with calls from anxious relatives of New Jersey residents, and in some places anxious groups discussed the impending menace of a disastrous war. Most of the listeners who sought more information were widely confused over the reports they had heard, and many were indignant when they learned that fiction was the cause of their alarm. In San Francisco the general impression of listeners seemed to be that an overwhelming force had invaded the United States from the air, was in the process of destroying New York and threatening to move westward. "My God," roared one inquirer into a telephone, "where can I volunteer my services? We've got to stop this awful thing." Newspaper offices and radio stations in Chicago were swamped with telephone calls about the "meteor" that had fallen in New Jersey. Some said they had relatives in the "stricken area" and asked if the casualty list was available. In parts of St. Louis men and women clustered in the streets in residential areas to discuss what they should do in the face of the sudden war. One suburban resident drove fifteen miles to a newspaper office to verify the radio "report." In New Orleans a general impression prevailed that New Jersey had been devastated by the "invaders," but fewer inquiries were received than in other cities. In Baltimore a woman engaged passage on an airliner for New York, where her daughter is in school. The Associated Press gathered the following reports of reaction to the broadcast: At Fayetteville, N. C., people with relatives in the section of New Jersey where the mythical visitation had its locale went to a newspaper office in tears, seeking information. A message from Providence, R. I., said: "Weeping and hysterical women swamped the switchboard of The Providence Journal for details of the massacre and destruction at New York, and officials of the electric company received scores of calls urging them to turn off all lights so that the city would be safe from the enemy." Mass hysteria mounted so high in some cases that people told the police and newspapers they "saw" the invasion. The Boston Globe told of one woman who claimed she could "see the fire," and said she and many others in her neighborhood were "getting out of here." Minneapolis and St. Paul police switchboards were deluged with calls from frightened people. The Times-Dispatch in Richmond, Va., reported some of their telephone calls from people who said they were "praying." The Kansas City bureau of The Associated Press received inquiries on the "meteors" from Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, Beaumont, Texas, and St. Joseph, Mo., in addition to having its local switchboards flooded with calls. One telephone informant said he had loaded all his children into his car, had filled it with gasoline, and was going somewhere. "Where is it safe?" he wanted to know. Atlanta reported that listeners throughout the Southeast "had it that a planet struck in New Jersey, with monsters and almost everything and anywhere from 40 to 7,000 people reported killed." Editors said responsible persons, known to them, were among the anxious information seekers. In Birmingham, Ala., people gathered in groups and prayed, and Memphis had its full quota of weeping women calling in to learn the facts. In Indianapolis a woman ran into a church screaming: "New York destroyed; it's the end of the world. You might as well go home to die. I just heard it on the radio." Services were dismissed immediately. Five students at Brevard College, N. C., fainted and panic gripped the campus for a half hour with many students fighting for telephones to ask their parents to come and get them. A man in Pittsburgh said he returned home in the midst of the broadcast and found his wife in the bathroom, a bottle of poison in her hand, and screaming: "I'd rather die this way than like that." He calmed her, listened to the broadcast and then rushed to a telephone to get an explanation. Officials of station CFRB, Toronto, said they never had had so many inquiries regarding a single broadcast, the Canadian Press reported.

Washington May ActReview of Broadcast by the Federal Commission PossibleSPECIAL TO THE NEW YORK TIMESWASHINGTON, Oct. 30.—Informed of the furor created tonight by the broadcasting of Wells drama, "War of the Worlds," officials of the Federal Communications Commission indicated that the commission might review the broadcast. The usual practice of the commission is not to investigate broadcasts unless formal demands for an inquiry are made, but the commission has the power, officials pointed out, to initiate proceedings where the public interest seems to warrant official action.

Geologists at Princeton Hunt 'Meteor' in VainSPECIAL TO THE NEW YORK TIMESPRINCETON, N. J., Oct 30.—Scholastic calm deserted Princeton University briefly tonight following widespread misunderstanding of the WABC radio program announcing the arrival of Martians to subdue the earth. Dr. Arthur F. Buddington, chairman of the Department of Geology, and Dr. Harry Hess, Professor of Geology, received the first alarming reports in a form indicating that a meteor had fallen near Dutch Neck, some five miles away. They armed themselves with the necessary equipment and set out to find a specimen. All they found was a group of sightseers, searching like themselves for the meteor. At least a dozen students received telephone calls from their parents, alarmed by the broadcast. The Daily Princetonian, campus newspaper, received numerous calls from students and alumni.

Mars Monsters Broadcast Will Not Be RepeatedPerpetrators of the Innovation Regret Causing of Public AlarmWASHINGTON (AP) The radio industry viewed a hobgoblin more terrifying to it than any Halloween spook. The prospect of increasing federal control of broadcasts was discussed here as an aftermath of a radio presentation of an H. G. Wells' imaginative story which caused many listeners to believe that men from Mars had invaded the United States with death rays.When reports of terror that accompanied the fantastic drama reached the communications commission there was a growing feeling that "something should be done about it." Commission officials explained that the law conferred upon it no general regulatory power over broadcasts. Certain specific offenses, such as obscenity, are forbidden, and the commission has the right to refuse license renewal to any station which has not been operating "in the public interest." All station licenses must be renewed every six months. Within the commission there has developed strong opposition to using the public interest clause to impose restrictions upon programs. commissioner T. A. M. Craven has been particularly outspoken against anything resembling censorship and he repeated his warning that the commission should make no attempt at "censoring what shall or shall not be said over the radio." "The public does not want a spineless radio," he said. Objection to Terrorism. Commissioner George Henry Payne recalled that last November he had protested against broadcasts that "produced terrorism and nightmares among children" and said that for two years he had urged that there be a "standard of broadcasts." Saying that radio is an entirely different medium from the theater or lecture platform, Payne added: "People who have material broadcast into their homes without warnings have a right to protection. Too many broadcasters have insisted that they could broadcast anything they liked, contending that they were protected by the prohibition of censorship. Certainly when people are injured morally, physically, spiritually and psychically, they have just as much right to complain as if the laws against obscenity and indecency were violated." The commission called upon Columbia Broadcasting system, which presented the fantasy, to submit a transcript and electrical recording of it. None of the commissioners who could be reached for comment had heard the program. The broadcasters themselves were quick to give assurances that the technique used in the program would not be repeated. Orson Welles, who adapted "The War of the worlds," expressed his regrets. Told Story Imaginative. The Columbia network called attention to the fact that on Sunday night it assured its listeners the story was wholly imaginary, and W. B. Lewis, its vice president in charge of programs, said: "In order that this may not happen again, the program department hereafter will not use the technique of a stimulated news broadcast within a dramatization when the circumstances of the broadcast could cause immediate alarm to numbers of listeners." The National Association of Broadcasters, through its president, Neville Miller, expressed formal regret for the misinterpretation of the program. "This instance emphasizes the responsibility we assume in the use of radio and renews our determination to fulfill to the highest degree our obligation to the public," Miller said. "I know that the Columbia Broadcasting system and those of us in radio have only the most profound regret that the composure of many of our fellow citizens was disturbed by the vivid Orson Welles broadcast. The Columbia Broadcasting system has taken immediate steps to insure that such program technique will not be used again." Chairman Frank R. McNinch, of the communications commission, declaring that he would withhold judgment of the program until later, said: "The widespread public reaction to this broadcast, as indicated by the press, is another demonstration of the power and force of radio and points out again the serious responsibility of those who are licensed to operate stations." Demand Investigation. NEW YORK (AP). Urgent demands for federal investigation multiplied in the wake of the ultra-realistic radio drama that spread mass hysteria among listeners across the nation with its "news broadcast" fantasy of octopus-like monsters from Mars invading the United States and annihilating cities and populaces with a lethal "heat ray." While officials at the Harvard astronomical observatory calmed fears of such a conquest by space devouring hordes from another planet with the wry comment that there was no evidence of higher life existing on Mars—some 40,000,000 miles distant—local and federal officials acted to prevent a repetition of such a nightmarish episode. As for the 22 year old "man from Mars" himself, Orson Welles, youthful actor manager and theatrical prodigy, whose vivid dramatization of H. G. Wells' imaginative "The War of the Worlds" jumped the pulse beat of radio listeners, declared himself "just stunned" by the reaction. "Everything seems like a dream," he said. The Columbia Broadcasting system whose network sent the spine chilling dramatization into millions of homes issued a statement expressing "regrets" and announced that hereafter it would not use the "technique of a simulated news broadcast" which might "cause immediate alarm" among listeners. Military Lesson Taught. WASHINGTON (AP). Military experts here foresee, in time of war, radio loudspeakers in every public square in the United States and a system of voluntary self-regulation of radio. This is the lesson they draw from Sunday night's drama about an invasion by men from Mars armed with death rays. What struck the military listeners most about the radio play was its immediate emotional effect. Thousands of persons believed a real invasion had been unleashed. They exhibited all the symptoms of fear, panic, determination to resist, desperation, bravery, excitement or fatalism that real war would have produced. Military men declare that such widespread reactions shows the government will have to insist on the close co-operation of radio in any future war. The experts believe this could be accomplished by voluntary agreement among the radio stations to refrain from over-dramatizing war announcements which would react on the public like Sunday night's fictional announcement. They recall that the newspapers adopted voluntary self-regulation during the World war and worked in close co-operation with the government. Moreover, since radio admittedly has so immediate an effect, the experts believe every person in the United States will have to be given facilities for listening in if war ever comes. Consequently radios with loud speakers will have to be installed in all public squares, large and small. Persons not having radios in their homes can listen in through those. Canada to Take No Action. TORONTO (Canadian Press). Gordon Conant, attorney general of Ontario, said his department did not plan action over the broadcast of a realistic radio drama which, emanating from the United States and re-broadcast here, caused widespread alarm. "I don’t know of any action we could take," Conant said. "The difficulty is that only after these things happen can it be decided that they are not in the public interest. It is certainly not in the public interest that such broadcasts should be allowed."

Radio Chain Heads CalledBroadcast Problem Raised by the Welles Program.WASHINGTON (INS). Presidents of the nation's three major broadcasting chains were invited by Chairman Frank R. McNinch, of the federal communications commission, to a conference here late next week to discuss the use of the newspaper term "flash" on radio programs. McNinch issued the invitations to the presidents of the National Broadcasting company, the Columbia Broadcasting company and the Mutual Broadcasting system, he said, to discuss "especially the frequent and, at times, misleading use of the newspaper term 'flash.'"This step was taken by the FCC chairman in connection with last Sunday night's broadcast, "The War of the Worlds." The word "flash" was used in the broadcast to dramatize the H. G. Wells' imaginative story of an attack on this planet by "monsters from Mars." Many protests were received by the commission against the broadcast. The commission will meet in secret session next week to listen to a reproduction of the dramatization as recorded on discs. The conference with the radio chain chieftains will follow. In announcing the conference, McNinch said: "I have heard the opinion often expressed within the industry as well as outside that the practice of using 'flash,' as well as 'bulletin,' is overworked and results in misleading the public. It is hoped and believed that a discussion on this subject may lead to a clearer differentiation between bonafide news matter of first rank importance and that which is of only ordinary importance or which finds place in dramatics or advertising."

Book Excerpts, by Prof. David L. MillerDavid L. Miller, a professor of sociology at Western Illinois University, has given me permission to include some excerpts from his recently published book, "Introduction to Collective Behavior and Collective Action" (Waveland Publishing, Inc. (2000), ISBN 1-57766-105-2). The book devotes several pages to a discussion of the War of the Worlds broadcast, which Miller says has been a "sociological hobby" of his for nearly 30 years. Miller believes (and says he is not original in this view) that "in the days following the broadcast, the print media greatly exaggerated the nationwide reaction. In part, this was because it was a darn good story, but also because the print media were greatly concerned with the degree to which radio was cutting into their preserve of reporting the news."

CHAPTER 5 Hadley Cantril's (1966) study of the War of the Worlds broadcast and Donald M. Johnson's (1945) study of the Phantom Anesthetist are considered to be classic studies of mass hysteria. [...] Probably the most widely known event to be generally considered a mass hysteria occurred on Sunday evening, October 30, 1938. Orson Welles and his CBS Mercury Theater group presented an adaptation of one of H. G. Welles's then lesser-known short stories, "The War of the Worlds," which described a nineteenth-century Martian invasion of England. The Mercury Theater adaptation was set in the present (1938) and took place in the United States. Perhaps Welles's most consequential decision was to use an "open format" during the first half of the show. Instead of using the conventional dramatic format of background music, narration, and dialogue, the first announcements of the Martian invasion took the form of simulated news bulletins, interrupting a program of dance music. Welles's second most consequential decision was to use the names of actual New Jersey and New York towns, highways, streets, and buildings when describing the movements and attacks of the Martians. These two decisions, plus the fact that most listeners tuned in eight to twelve minutes late and therefore missed the Mercury Theater theme and introduction, set the stage for what was to follow. Thousands of people across the United States assumed they were listening to real news bulletins and public announcements. A substantial portion of these listeners became very frightened and attempted to call police, the National Guards, hospitals, newspapers, and radio stations for information. In addition, people tried to contact family members, friends, and neighbors. By the time Mercury Theater's first station break came, informing people they were listening to a CBS radio drama, most of the broadcast's damage had been done. The next day, newspapers across the country carried stories of terrorized people hiding in basements, panic flight from New Jersey and New York, stampedes in theaters, heart attacks, miscarriages, and even suicides. During the months that followed, these stories were shown to have little if any substance, yet today the myth of War of the Worlds stampedes and suicides persists as part of American folklore. One clear and certain result of the broadcast, however, was a number of Federal Communication Commission regulations, issued within weeks of the broadcast, prohibiting the use of the open format in radio drama. [...] Cantril's (1966) study of "The War of the Worlds" broadcast concludes that about 20 percent of those listening to all or part of the broadcast exhibited hysterical panic reactions. [...] Without question, listeners were frightened by the War of the Worlds broadcast; Mattoon residents were convinced their dizziness and nausea were caused by the phantom's gas; workers were hospitalized for days with rashes, rapid heart beat, and nausea during the June bug epidemic; and farmers were convinced their cattle had died in a mysterious manner. Those who studied these events from the standpoint of mass hysteria described these reactions as psychogenic or mass sociogenic illness. In other words, from the standpoint of mass hysteria, fear reactions to the War of the Worlds broadcast were abnormally severe, given the nature of the show. Likewise, it was concluded that the physical symptoms reported in the Riverside emergency room, during the Stairway of the Stars concert, and during the phantom anesthetist and June bug episodes had no organic cause. It was also concluded that the mysterious cattle mutilations were either totally imaginary or the work of scavengers combined with normal decomposition. [...] The weakness of the psychogenic explanation is perhaps most obvious when we consider the reactions to the War of the Worlds broadcast. Again, we should emphasize that the War of the Worlds was not an ordinary radio drama. As mentioned above, the first half of the show used an open format in which the entire story line was developed through the use of simulated news bulletins and on-the-scene reports. The second half of the show used a conventional dramatic format. Many discussions of the War of the Worlds read as if listeners panicked at the very beginning of the broadcast and remained terrorized throughout the show and much of the evening. In fact, a ten-minute segment in the first half of the broadcast caused most of the trouble. In the days following the show, newspaper columnists and public officials expressed dismay at the "incredible stupidity," "gullibility," and "hysteria" of listeners. Many popular accounts claim that the broadcast was interrupted several times for special announcements that a play was in progress. Listeners, however, had apparently been too panicked to notice them. These extreme psychogenic assumptions are, for the most part, unwarranted and inaccurate. For example, other than Mercury Theater's one-minute introduction (which most listeners missed), the station break at the middle of the broadcast, and the signoff, there were no announcements, special or otherwise, to indicate that a play was on the air. Further, Mercury Theater was being presented by CBS as a public service broadcast, and there were no commercials from which listeners might conclude that they were listening to a drama (Houseman 1948). Cantril (1966) and Houseman (1948) indicate that most listeners, and virtually all of those who became frightened, tuned in Mercury Theater about twelve minutes after it began. These listeners joined the broadcast during an on-the-scene news report from a farm near Grovers Mill, New Jersey-an actual town located between Princeton and Trenton-where a large meteor had landed. Welles's careful direction meticulously created all the character of a remote broadcast, including static and microphone feedback and background sounds of autos, sirens, and the voices of spectators and police. Twelve minutes from the beginning of Mercury Theater newscaster Carl Phillips (played by radio actor Frank Readick) was concluding a rather awkward interview with a Mr. Wilmuth, the owner of the farm where the meteor had landed. Phillips broke off his interview with the annoyingly inarticulate Mr. Wilmuth by providing listeners with a detailed description of the meteor. During this description, Phillips called the listeners' attention to mysterious sounds coming from the meteor, and fought to maintain his composure as he described the incredible and horrible creatures emerging from the pit where the meteor had landed. Background sounds of angry police and confused, frightened, and milling spectators provided a brilliant counterpoint to Phillips's stammering narration. At this point, Phillips signed off temporarily to "take up a safer position" from which to continue the broadcast. For what seemed a very long time, a studio piano played "Clair de Lune," filling in the empty airspace. Finally, an anonymous studio announcer broke in with, "We are bringing you an eyewitness account of what's happening on the Wilmuth farm, Grovers Mill, New Jersey." After more empty airspace, Carl Phillips returned. Apparently unsure of whether he was on the air, Phillips continued to describe the monsters. The tempo of his reporting increased until Phillips was almost incoherent. In the background, the sound of terrified voices, screams, and the monsters' strange fire weapon merged into a chaotic and hair-raising din. Then, abruptly, there was dead silence. After an unbearably long period of empty airspace, the studio announcer broke in with, "Ladies and gentlemen, due to circumstances beyond our control, we are unable to continue the broadcast from Grovers Mill. Evidently there is some difficulty in our field transmission" (Cantril 1966:17-18). This segment of the broadcast lasted less than five minutes, but, according to later interviews, it caused most of the fright. The technical brilliance of the broadcast aside, how could an event as seemingly unlikely as a Martian invasion be readily interpreted as real? Part of the answer to this question lies in the fact that the monsters were never clearly identified as Martians until several minutes after Carl Phillips's segment of the broadcast. It is likely that some people who became confused and frightened was Frank Readick's interpretation of an on-the-scene news reporter. Readick was inspired by the eyewitness description of the explosion of the zeppelin Hindenburg, which had occurred on May 6, 1937, at Lakehurst, New Jersey. In this world-famous broadcast, the reporter was describing the uneventful landing of the Hindenburg when it suddenly exploded with spectacular and deadly force. The reporter struggled to remain coherent, and his tearful, second-by-second description was heard by millions. The day of the War of the Worlds broadcast, Readick spent hours listening to the Hindenburg recording (Houseman 1948). His interpretation of the Martian attack created a sense of deja vu. The emotion, the stammering, and even the tempo of Carl Phillips's narration reminds one of the Hindenburg disaster. Frank Readick's blending of the real and imaginary must have been very disconcerting for those who had heard the Hindenburg broadcast eighteen months earlier. After Carl Phillips's "death" and until the first station break, the broadcast consisted of a collage of news bulletins, public announcements, and on-the-scene reports. Taken sequentially, these bulletins and reports seemed to describe the Martians' utter destruction of the New Jersey National Guard, a devastating Martian advance across New Jersey, and, by the end of the first half of the show, massive nerve gas attacks on New York City. Events of such magnitude could hardly occur in a period of less than fifteen minutes. About 25 percent of the listeners who had become frightened quickly concluded that they were listening to a radio drama because of this time distortion and other internal inconsistencies of the broadcast (Cantril 1966:106-107). Most of the frightened listeners did not perceive the impossibility of a fifteen-minute sweep of the East Coast by Martians. Cantril describes these people as experiencing the most severe symptoms of panic: their critical abilities had been so swept away that they continued to believe the impossible. Cantril's data, however, suggest an alternate interpretation of this group's behavior. Quite simply, many of Cantril's interviews suggest that listeners perceived the reported events as occurring simultaneously rather than sequentially. Nothing in the first part of the broadcast definitely stated that the Martians who had landed at Grovers Mill were the same Martians who, moments later, were reported to be marching across New Jersey or attacking New York City. Listeners who failed to perceive a time distortion in the broadcast had not necessarily lost their critical abilities. Rather, they were perceiving the news bulletins and on-the-scene reports as an understandably confusing and disordered collage of information pouring in simultaneously from all across the nation. The psychogenic, or hysteria, explanation of people's reactions to the War of the Worlds broadcast severely underplays the unique and unsettling character of the show. Cantril poses the question: "Why did this broadcast frighten some people when other fantastic broadcasts do not?" He provides a partial answer when he considers the realistic way in which the program was put together (Cantril 1966:67-76). Houseman (1948) provides even more insight when he discusses the "technical brilliance" of the show that emerged under Orson Welles's direction. If we take into account the unique character of the War of the Worlds broadcast, we needn’t speculate that psychogenic mechanisms caused people to lose their critical ability and then to panic. Rather, Orson Welles and his Mercury Theater staff of excellent writers and actors not so innocently conspired to "scare the hell out of people" for Halloween. They succeeded in scaring the hell out of 20 percent of their listening audience. In summary, the quantitative mass hysteria studies fail to show that the unusual and unverified experiences are widespread. In some instances, these experiences are reported by a very small portion of an available population, and in no instance are they reported by a majority. The quantitative studies also fail to clearly substantiate the hysterical nature of unusual and unverified experiences. Some studies have relied almost totally on the judgment of law enforcement or medical authorities that the reported experiences are of a hysterical nature. Cantril, on the other hand, fails to take the unique features of the War of the Worlds broadcast into account when he concludes that the fear reactions were hysterical in nature. Mass hysteria studies generally fail to distinguish mobilization as a distinct element of the episodes that prompted the investigations. Cantril, for example, alleges that panic flight occurred during the War of the Worlds broadcast but does not systematically examine his data to determine the extent or characteristics of this flight. Cantril also notes that telephone switchboards at CBS, local radio stations, police, and hospitals were flooded with calls from hysterical people. Again he made no systematic attempts to ascertain the nature of these calls. Likewise, Johnson (1945) noted that Mattoon residents formed neighborhood patrols during the anesthetist incident, but he did not attempt to find out when these patrols occurred or determine their size, composition, and activities. Such types of mobilization are probably more burdensome to authorities and disruptive of social routines than are the unusual and unverified experiences. Even though the mass hysteria studies fail to systematically examine mobilization, they do present information that, when carefully considered, provides some insight into this process. Though Cantril's data does not document the claim that the War of the Worlds broadcast produced substantial amounts of panic flight, a few of his interviews suggest that some people started to pack belongings in preparation for movement before they found out the news bulletins were a play. In only one instance, however, does Cantril (1966:54) discuss a person attempting to get away from the Martian attack, without regard for future consequences. Cantril received a letter from a man who spent $3.25 of his meager savings to buy a ticket to "go away." After the man found out it was a play, the letter continued, he realized he no longer had enough money to buy a pair of workshoes. The last part of the letter contained a request for size 9B workshoes. Houseman (1948:82) reports that Mercury Theater received a similar request for size 9B workshoes which they sent in spite of their lawyers' misgivings. The story of the man who decided to forgo workshoes in order to escape the Martians has a decided ring of the apocryphal.

Rick KeatingDate: Mon, 23 Nov 2009 23:06:52 -0500From: Rick Keating pkeating89@yahoo.com To: old.time.radio@oldradio.net Subject: Speaking of War of the Worlds I've been meaning to bring this up since Oct. 30, but I've been busy. When I listened to "War of the Worlds" on Oct. 30, I decided to page through a book I own called The War of the Worlds: Mars' Invasion of Earth, inciting panic and inspiring terror from H.G. Wells to Orson Welles and Beyond by Sourcebooks MediaFusion. In doing so, I saw that the book, which I hadn’t looked at in some time, contained the script for the radio show. So I decided to follow along for a bit. And I noticed some differences between the script and the broadcast. The first instance I made note of sounds like there's a fault in the original transcription disc. It's the part where Professor Pierson says "I look down at my blackened hands, my torn shoes, my tattered clothes..." I own six copies of the "War of the Worlds" broadcast on both tape and CD, and a quick check of three of them, the Radio Reruns tape, the CD version that came with the book, and the CD in the collection "Radio Tune in the Golden Age: The Classic Collection", all had a "skip", if you will, after "blackened hands", jumping to "and I try to connect them with a professor who lives at Princeton." And I don’t remember ever hearing the lines about torn shoes and tattered clothes (whether hearing the show over the radio or on tape or CD), so I'm guessing my other three copies-- and all other copies-- of the episode are all missing those few words. Or does anyone have a copy that doesn’t skip over that small bit? The second instance I noted comes not long after, as Professor Pierson reflects on how strange it is to be back in his study, life returned to normal. After describing how strange it is to be writing this last chapter in his study, Pierson says, "Strange to see the University spires dim and blue through an April haze. Strange to watch children playing in the streets." The three copies I checked are all missing that first sentence, and there's no "skip", as there was in the earlier example. Nor do I remember ever hearing the line about the university spires. Does anyone have a copy of the broadcast with that sentence about the university spires? If not, then it could be that the Welles and/or the cast made some last minute edits to the script and cut that line before broadcast. On the other hand, if people do have copies of the broadcast with that sentence included, it suggests later edits done, perhaps, as someone suggested in an earlier digest, to make room for commercials when "The War of the Worlds" was aired on some station around Halloween. I'm pretty sure there's one or two earlier examples of the broadcast differing from the script, but I didn’t mark those pages in the book that day. In any event, as I said, I don’t recall ever hearing those missing bits I described above. But I was curious whether anyone had, in either case. In any event, it might tell me whether I have later generation recordings. While I've never listened to all six copies one after the other, I have heard the story so many times that if there were any major differences, I'd have noticed it at the time and made note of it in my Radioshows database. So I'm guessing that were I to undertake such a task, I'd only notice various degrees of surface noise, improvements in sound quality, etc. The other three copies I own, for the record, are included in the collections "Old Time Radio Science Fiction" (Smithsonian Collection) and "The Greatest Old Time Radio of the 20th Century" and a tape from "The World's Greatest Old Time Radio Shows." For what it's worth, I don’t believe there's a second version, and whenever I've heard the episode, whether over the radio or on tape or CD, it's always been Ramon Raquello, never anyone else. Rick

Michael BielDate: Sun, 31 Oct 1999 15:33:12 -0500From: Michael Biel (mbiel@kih.net) To: old.time.radio@lofcom.com Subject: Re: War of the Worlds—Who Was First? While listening to the classic "War of the Worlds" tonight a question occurred to me: When was the first time this program was rebroadcast? This question is complicated because there are two ways this program can be "rebroadcast." One is by replaying the recording of the original, and the other is by doing a new broadcast of the original story. In the first instance—rebroadcasting the original recording—there are two necessary factors. One is having the recording itself, and the other is the interest in rebroadcasting OTR in general. Until an incomplete version was released on Audio Rarities LPA 2355 in 1955 by Sidney Frey of Dauntless International, a recording of the original broadcast was not generally available. And during those years of the decline of radio drama's popularity it was not yet "hip" to be nostalgic about the golden age of radio. That didn’t come until about ten years later, around 1965 and 1966. It is probable that a few stations might have played the recording during those years. I was listening to OTR on Sunday nights on WVNJ Newark, and Dave Golden was making occasional appearances on WBAI, New York. They might have done it. An obvious time would have been the 30th anniversary in 1968, but on that night something else happened. Rock station WKBW, Buffalo, New York did an altogether new version of the story in their top-40 radio style using their own DJs and news department personnel on Oct 30, 1968. It is one hell of a performance, and it beats the Orson Wells original hands down. It is far more convincing, and is more consistent with contemporary 1968 radio than the original had been to 1938 radio. And the ending is different—not altogether a conclusive finish nor a happy ending. The following year they rebroadcast the tape and in the preface they described what had happened the previous year. They had done a lot of promotion of the program and had sent press releases and info to all of the public service agencies that might be affected, such as police, fire, civil defense, etc. Yet some of these agencies reacted to the bulletins in spite of having been given prior notice of what was being done. And they even got calls from listeners LISTENING TO THE BROADCAST asking when the broadcast was going to begin. That is how smoothly the style of the broadcast blended in with the everyday style of the station. They played records, did commercials, played their jingles, and covered the story like they regularly covered stories. It is a masterpiece. On a similar note, back around 1950 a station in Caracas, Venezuela likewise did an updated localized version and it was so effective a mob burned the station down when they discovered it was a hoax. Some station personnel died. There is a well researched article about this on a web site. (Anybody have its URL? The author was on the other OTRlist.) Conversely, National Public Radio did a "public radio" version on the 50th anniversary in 1988 that in my opinion stinks to high heaven. With a script modified by the original author Howard Koch, and using a highly overrated cast and sound effects done by Lucas' Skywalker Ranch personnel led by Randy Thom, it is extraordinarily unconvincing and dull presentation. I don’t recall hearing anything about NPR making it available for rebroadcast ever since, and I hope that this sham remains buried. They made it available for a limited time as a cassette and a one-track CD. Those dunderheads didn’t even have the common sense to put in cue points for different scenes as tracks on the CD. (Unfortunately they are not the only idiots who put out CDs like that.) There's one other factor about rebroadcasting the original 1938 program. The complete recording that we now have was not circulated until around 1971. I had been given a tape of it—complete with surface noise during the station break—about a year before the LP first came out, so it was available to a select few, but I don’t recall hearing it on the air until after the Evolution LP was issued.

Michael Biel

From: "MICHAEL BIEL" mbiel@kih.net To: old.time.radio@oldradio.net Subject: War of the Worlds station break I've mentioned before that I have a tape of the original War of the Worlds discs that includes the full length of the mid-program station break. This was edited out of the recording when the LPs of it were released, but my tape, which I obtained a year or so before the LPs came out, includes the silence and the slight surface noise of the original disc. I came across the tape this evening, and here is the all-important piece of information. The station break was twenty seconds long. So, if you are concerned about the accuracy of the timing of the recording you have, add twenty seconds to it to determine what the total length of the program was. It should be around 59:00 to 59:15 I suppose. I am not sure of what the length of a CBS hourly station break was in 1938. Michael Biel mbiel@kih.net

From: "MICHAEL BIEL" mbiel@kih.net To: old.time.radio@oldradio.net Subject: War of the Worlds recordings Chris Holm noted that someone had cast doubts on the WOTW recording, saying it was a re-creation done the following week. I doubt that because that would be evident in the cast call sheets for the following week, since there would have been some different members and effects people needed for the two different programs. There IS a possibility that it is the rehearsal recording because there have been statements that the rehearsals of Mercury Theatre were listened to before the final airings. But I tend to doubt even this possibility. What I CAN tell you is this: The recording we know was credited to Manheim Fox when it was first issued on LP in the late 60s. The year before that first LP issue of this version, I was given a tape of this recording that includes surface noise for thirty seconds after the ID break announcement and before the re-join announcement. There is silence for 30 seconds—only surface noise. Thus, this is a line check recording. No other recording of these discs includes that break. I doubt that a re-creation the week after would have kept in the break at 30 seconds length. While a rehearsal might have done so to keep the timing exact, I also think that a rehearsal might have broken for a time-out break at that point, to relax, go over notes, and to regroup. In the 1950s, Sydney Frey issued an incomplete recording on Audio Rarities. The opening, closing, ID break announcements, and one other section are missing. The sound quality and surface noise are quite different. However, there is no doubt whatsoever that it is of the same performance. Although I have been in touch with Frey's daughter, I do not know if the original discs are still in her files. I also have a story of how this set might have been come to have been recorded and how her father might have gotten them. No confirmation from her as she was too young then to be involved. In a recent newspaper article about the CBS News Archive, there is a photograph of the archivist holding a yellow-labeled 16-inch disc that the caption says is the WOTH. I can tell you that this was not in the disc collection of CBS News when I saw the collection in the early 70s. Its the first thing I looked for. The entertainment division had a different archive that I have never been able to crack, and the discs might have been there. I and another digest member had been offered a set of WOTW discs at separate times, and both of us noted that the discs were dated as being a 1948 dub. I seem to recall a scan of yellow labels. Maybe that is what CBS now has. In the 1970s I was told by a man who had later become a supervising engineer at CBS that when he was new at CBS he had actually been the one to cut the discs of the program at CBS and had been ordered to smuggle the discs out of CBS. He told me that they were later lost, I think, when his kid brought them in to school for show-and-tell. A few years earlier I was shown a set of 12-inch lacquers in the possession of a very famous collector of a genre other than OTR. Did he get them at school?? But on the other hand, I was specifically told by another long-time CBS engineer who used to be a digester member that CBS New York never had any disc cutting equipment, just like CBS Hollywood never had any either. Yet my other source said he was there when a pair of disc cutters was installed at 485 Madison Ave.in September 1938 in time for the Munich Crisis. Is this starting to read like The DaVinci Code? I have been asked to be on a WOTW panel for next years FOTR. It has been my intention to try to follow up these leads. Wish me luck. And by the way, does anybody have any contact with Manny Fox? Is he still alive? Can someone confirm that he is not Sonny Fox? Michael Biel mbiel@kih.net

From: mbiel@windstream.net To: old.time.radio@oldradio.net Subject: Re: Martians land in upstate New York Bill Jaker reported that WSKG was going to do a live recreation of WOTW with an audience and live music. I found out this morning (also too late to listen) that Ball State University in Indiana also did a live production with an audience and live music Thursday night. And while Bill says there will be someone there who had heard the original, Ball State says there will be someone at their production who had been in the CBS Building at the time of the broadcast. Bill also said: There's been concern expressed here on the Digest and elsewhere about some re-enactments turning campy, shifting the scene out of New Jersey to the local area or just not getting it right." I suppose that we could put the 1988 NPR version in that category, since I don’t think it was very effective. Doing a "re-creation" of how it was done in 1938 will not have any effect, nor will just a minor update as NPR did in 1988. But it CAN be effective if the script is thrown out the window and a complete update to modern style is done. Last week I did a presentation at both FOTR and at the NYC branch of the Assoc for Recorded Sound Collections about WOTW and MacLiesh's "Air Raid" which had been broadcast by CBS three days before WOTW with some of the same cast members. In addition to playing some segments of "Air Raid" (one generation away from the original 78 discs) and playing the middle break of WOTW complete with the previously unheard 20 seconds of surface noise where a station ID would have been inserted, I also discussed four other later productions of WOTW which had updated and changed the location to that of their local area to great effect. They were Santiago, Chile in 1944, Braga, Spain on Oct 30, 1988, WKBW Buffalo NY on Oct 30, 1968, and Quito, Ecuador on Feb 12, 1949. While there were some fright and outrage in the first three of these, in Quito the outraged mob stormed the radio station and BURNED IT DOWN, killing between 6 and 20 people. You can look up info on the web on these, but I played some segments of the WKBW broadcast that are not on their website. I have an aircheck of the 1969 repeat which I am not sure they even know about. One of my students had recorded it off the air in New Jersey, so there is fading once in a while. Here the update to the 1968 sound of The Big KB is VERY effective, much more than any other I have heard. I had a lot of people ask me where the complete broadcast is available, and it isn’t yet until I can locate the tapes which got moved from my office in the past few months. I'll post here when I have found it and have it ready. Michael Biel mbiel@mbiel.com

Elizabeth McLeodDate: Sun, 13 Oct 2002 09:30:06 +0000From: Elizabeth McLeod lizmcl@midcoast.com To: old.time.radio@oldradio.net Subject: Re: WOTW Competition I know this was brought up one or two years ago on the OTR Digest, but I have forgotten the answer. What were MBS and NBC Blue airing at 8pm EST on October 30th, 1938? Those Mutual stations that hadn’t sold the time period locally had the option of carrying a sustaining musical program presented by the WOR Symphony under the direction of Alfred Wallerstien. A major chunk of Mutual did not carry this broadcast—the Colonial Network in New England carried Father Coughlin's paid program instead. Blue stations were offered another sustaining program, "Out of the West," a musical feature from San Francisco with Ernest Gill and his Orchestra, which they could carry if they hadn’t sold the time locally. Given that the Chase & Sanborn Hour was, according to Hooper, the most popular program on the air during the fall of 1938, it's not surprising that the Sunday-night-at-8 timeslot was essentially a throwaway period for the other networks—or, in the case of CBS, a chance to turn unsalable time into a public-relations writeoff by positioning itself as a "Patron of the Arts." An hour-long drama series based primarily on public-domain works, cast with actors working for scale, was a low-budget way for the network to eat a timeslot no one wanted, and the fact that Welles happened at that time to be the darling of the New York Intellectual crowd enabled CBS to look good while doing it. Of course, no one was counting on the sort of publicity they ended up getting.... Elizabeth

From: Elizabeth McLeod lizmcl@midcoast.com To: old.time.radio@oldradio.net Subject: Re: WOTW Sources Does anyone know what we're listening to as far as the original "War Of The Worlds" broadcast? Are they all copies of copies of copies? Is there a single original transcription disc? There are apparently several sets of copy discs extant, with at least one set known to have been dubbed at Radio Recorders in Hollywood in 1948—a set evidently dubbed onto 16" blanks from 12" 78rpm copy discs, making it probably third generation at best. Copy discs are not originals, do not sound like originals, and should not be considered originals—and certainly shouldn’t bring the price of originals. However, a set of WOTW discs was auctioned off last year by the estate of Ralph Murchow, a prominent collector of radios and radio equipment for $14,000—and while I've never seen any positive authentication for these discs, it appears from a picture online (http://www.estesauctions.com/muchowpictures.html) that these could be originals. The discs appear to be Presto Green Label "Q" lacquer blanks—and this was in fact a professional grade of blank disc that was widely used for broadcast recordings in 1938. There are no paper labels visible—either they've fallen off or were never applied, and it's impossible to read the inscription in the picture to see if it sheds any light on the origin of these discs. There have been a lot of stories over the years about "original discs"—someone approached me a couple of years ago about appraising a set of "original WOTW discs" for insurance purposes—but when they wouldn’t at least show me a scan of the discs I got very suspicious. There are plenty of stories in circulation about "friends of friends' fathers who had a set of discs"—but without expert authentication, I would take all such stories with a carload of salt. Even if these $14,000 discs are originals, though, the audio quality depends a lot on where along the network line they were recorded. The only way to get a studio-quality recording of WOTW is to find a set of discs recorded directly off the program amplifier—and CBS wasn’t doing this in 1938, instead using various contract studios when recordings of various programs were needed. The quality of any discs found would be limited by the quality of the line linking the network to the recording studio. A recording of WOTW made off the line in Hollywood will be inferior in sound quality to a recording made off the line in New York. I can still hear their "noise gates" (makes quiet portions of audio even quieter, like silences between words, etc) working on my best copies of WOTW, I think that today's processing equipment is more transparent - am I hoping for too much? I have heard some other audio cleanups that are like NIGHT and DAY, absolutely incredible. Can that be done to the original WOTW recording? Maybe it already has, the original sounds like garbage, and with cleanup sounds as good as it ever will, now. So far as my own ears are concerned, none of the "digitally restored" CD versions of WOTW are worth owning—they seem to all be bootlegged off the early 1970s LP issue, and attempt to mask the surface noise of that version with poorly-applied noise reduction. Until and unless a set of authenticated original discs shows up for a real remastering, a mint/near mint copy of the LP, properly transferred, is probably the best bet for decent audio quality. This LP is dirt common, and can still be had fairly cheaply on eBay, although sealed copies are harder to find. In addition to the original double-LP issue, Evolution 4001, this transfer was reissued on the Murray Hill label (44217) and—as a single disc—on Longines Symphonette (4001), with all versions using the same cover art depicting the front page of the New York Daily News from the morning after the broadcast, against a lurid red-orange background. Look for the "Released by arrangement with Manheim Fox Enterprises" credit line on the jacket and the disc label to ensure you're getting the right one. If I had to choose, an original Evolution pressing would probably sound best, but the Murray Hill or Longines versions will still be better than any modern CD issue. The source discs for the Manheim Fox-authorized issue remain a mystery, at least to me. They are clearly not the 1948 copy discs. Has anyone ever actually seen them? Might they be the same discs later owned by Ralph Murchow and just recently auctioned? Manheim Fox was a 1970s theatrical impresario who had some business connection to Howard Koch (his name also appears in connection with Koch's "Panic Broadcast" book) but that's as much as I know about him. There are other LP versions besides the authorized Manheim Fox releases—the first version issued came out on the Audio Rarities label in 1955, but was of very poor quality and was not complete. Avoid this one unless you're a manic WOTW collector—it's interesting to own as a curiosity, but it's really not worth listening to. Elizabeth

From: Elizabeth McLeod lizmcl@midcoast.com To: old.time.radio@lofcom.com Subject: Re: Another WOTW Question Hello. Recently, there has been a discussion of "War of the Worlds," so I thought I would ask my own question. I know that Charlie Mccarthy was on NBC, and the Mercury Theater was on CBS. But, what was on Mutual and the soon-to-be ABC network? I have not seen this discussed before. Most of Mutual's eastern and midwestern affiliates were carrying a program of classical music—part of a continuing series of Bach cantatas as performed by the WOR Symphony under the direction of Alfred Wallerstien. Not all MBS stations carried this, however—the Colonial network in New England broke away from Mutual to carry Father Coughlin, and it's likely that many other Mutual affiliates around the country did the same: Coughlin paid cash up front, and the Wallerstien musical show was an unsponsored sustainer. The NBC Blue network, meanwhile, was carrying "Out Of The West," a program of "narrated" dance music from San Francisco under the direction of Ernest Gill. This was also an unsponsored show. Of course, not all CBS stations carried the Mercury Theatre—the program was hard to hear in New England, where WEEI in Boston broke away from the network to carry a local public-affairs program in the eight-to-nine PM slot. Elizabeth

From: Elizabeth McLeod lizmcl@midcoast.com To: old.time.radio@oldradio.net Subject: Re: WOTW Studio With the 62nd anniversary of "War of the World" approaching, exactly where was the New York studio where the broadcast originated? If the building is still standing, is the studio still in use? CBS headquarters from 1929 thru 1964 were located at 485 Madison Avenue, a 25-story office building at the corner of Madison and 52nd in Manhattan. CBS didn’t own the building—they merely leased several floors, including studios, offices, and technical facilities. When they first moved in, the network occupied the twentieth thru the twenty-fourth floors (some of the studios were two stories high) but gradually took more space until CBS finally occupied ten floors of the building. WOTW was broadcast from Studio One, on the 20th Floor, home to most of CBS-NY's large-scale non-audience dramatic shows thru the radio era. The studio was converted for television in the late forties, and its designation changed to Studio 71. The building still exists, although it's been totally remodeled several times since CBS left. There is still a broadcasting presence—station WADO, a Spanish-language news-talk outlet, has its offices and studios on the third floor, but there are no links to the old CBS facilities. For many years, Mad magazine's editorial offices were at 485 Madison, but most of the building now houses a faceless assortment of public relations and law firms, insurance companies, and charitable foundations. On the ground floor you'll find a number of retail establishments, including a Leonidas chocolate shop and a "Body Shop" cosmetics store. On the 20th floor, CBS's former space is now occupied by a venture capital firm called "Northwood Ventures," with nothing remaining from the old days. Elizabeth