M-ESTIMATOR. In his "Robust Estimation of a Location Parameter," Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 35, (1964), 73-111 Peter J. Huber considers a class of estimators analogous to least squares but in which another function of the errors is minimised. Huber called such estimators "(M)-estimators." The brackets were later discarded and the abbreviation "M-estimator" has become standard.

MACLAURIN’S SERIES is named for Colin Maclaurin (1698-1746).

Maclaurin’s theorem appears in 1820 in A Collection of Examples of the Applications of the Differential and Integral Calculus by George Peacock [Google print search].

Maclaurin’s series appears in English in 1825 in An Elementary Treatise on the Differential and Integral Calculus by Rev. Dionysius Lardner. [Google print search by James A. Landau]

In 1849, An Introduction to the Differential and Integral Calculus, 2nd ed., by James Thomson has: "A particular case of this formula is commonly called Maclaurin’s theorem, because it was first made generally known by that writer. It had been given previously, however, by Stirling, another Scotch mathematician; and therefore, if a particular case of Taylor’s general theorem should be named after any other mathematician, this ought to be called Stirling’s theorem." Thomson subsequently uses the term Stirling’s theorem throughout the book.

McLaurin’s formula is found in English in 1855 in Elements of the differential and integral calculus by Albert Ensign Church [University of Michigan Digital Library].

Les séries de Taylor et de Maclaurin is found in 1870 in J. Bourget, "Note sur les séries de Taylor et de Maclaurin," Nouv. Ann.

C. B. Boyer A History of Mathematics (1968, p. 469) comments. "In view of the striking results of Maclaurin in geometry, it is ironic that today his name is recalled almost exclusively in connection with a portion of analysis in which he had been anticipated by some half dozen earlier workers."

MAGIC SQUARE is found in the title Des quarrez ou tables magiques by Frenicle de Bessy (1605-1675).

Magical squares appears in English in 1693 in A New Historical Relation of the Kingdom of Siam by Monsieur de La Loubere. [Google print search by James A. Landau]

Benjamin Franklin used the term in his autobiography:

This latter station was the more agreeable to me, as I was at length tired with sitting there to hear debates, in which, as clerk, I could take no part, and which were often so unentertaining that I was induc'd to amuse myself with making magic squares or circles, or any thing to avoid weariness; and I conceiv'd my becoming a member would enlarge my power of doing good.Franklin also used the term in a letter in which he wrote, "I make no question, but you will readily allow the square of 16 to be the most magically magical of any magic square ever made by any magician" (Cajori 1919, page 170).

MAHALONOBIS DISTANCE. This measure was introduced by Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis in his “On tests and measures of group divergence I. Theoretical formulae,” Journal and Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, 26, (1930) 541–588. The term Mahalonobis distance has only been widely used since the 1960s.

The term MANDELBROT SET was coined by Adrien Douady, according to an Internet web page.

The OED shows a use of the term in 1984 in the Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society: “Many important open questions regarding quadratics are best phrased in terms of the Mandelbrot set.”

MANIFOLD was introduced as Mannigfaltigkeit by Bernhard Riemann (1826-1866) in Grundlagen für eine Allgemeine Theorie der Functionen, published (posthumously) in 1867, Werke p. 3 [Mark Dunn].

Manifold is found in English in 1886 in Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute 1885. [Google print search by James A. Landau]

MANTISSA is a late Latin term of Etruscan origin, originally meaning an addition, a makeweight, or something of minor value, and was written mantisa. In the 16th century it came to be written mantissa and to mean appendix (Smith vol. 2, page 514).

Numerous sources, including Smith (vol. 2, page 524), Boyer (page 345), the Century Dictionary (1889-97), and Webster’s New International Dictionary (1909), claim that mantissa was introduced by Henry Briggs (1561-1631) in 1624 in Arithmetica logarithmica. However, this information apparently is incorrect. Johannes Tropfke in his "Geschichte der Elementar-Mathematik, vol. 2, 3rd edition 1933, says "Das Fachwort Mantisse hatte Briggs noch nicht" (p. 252). [Christoph J. Scriba]

According to Cajori (1919, page 152), the word mantissa was first used by John Wallis in 1693:

Ejusque partes decimales abscissas, appendicem voco, sive mantissam.The citation above is from "Opera mathematica," vol. 2, Oxoniae, 1693 (De Algebra tractatus), page 41. This is in the Latin edition, and not in the original edition of 1685, in which Wallis uses the English word "appendage." According to Julio González Cabillón, this is the first use of the term to mean "the decimal part of any number."

Mantissa was also used by Leonhard Euler in 1748:

Constat ergo logarithmus quisque ex numero integro et fractione decimali et ille numerus integer vocari solet characteristica, fractio decimalis autem mantissa. (The logarithm consists of an integral part, called the characteristic, and a decimal fraction, called the mantissa.)The citation above is from Euler’s Introductio in analysin infinitorum, vol. 1, page 83 (Lausannae 1748). According to Julio González Cabillón, this is the first use of the term to mean "the decimal part of a logarithm." According to Smith (vol. 2, page 514), the word was not commonly used until its adoption by Euler.

Gauss suggested using the word for the fractional part of all decimals: "Si fractio communis in decimalem convertitur, seriem figurarum decimalium ... fractionis mantissam vocamus ..." (Smith vol. 2, page 514).

MANY-VALUED is found in 1869 in “On Vortex Motion” by Sir William Thomson in Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (read April 29, 1867). [Google print search by James A. Landau.]

MAPPING. This term is a translation of the German Abbildung (illustration, drawing, map, etc.) whose use as a mathematical term can be traced back to Riemann and Klein.

The term—in German and then English—was originally confined to geometry as e.g. by F. Morley “On the Geometry Whose Element is the 3-Point of a Plane,” Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 5, (1900), 467-476. Morley refers to the notion of mapping in S. Kantor “Ueber eine ein-dreideutige ebene Abbildung einer Fläche dritter Ordnung,” Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik, 95, (1883), 147-164.

Later the term was used more abstractly as e.g. in H. P. Robertson’s 1931 translation of H. Weyl’s Theory of Groups and Quantum Mechanics p. 110 “A mapping or correspondence S ... is determined by a law which associates with each point p of the field a point p' as image.” (cited in the OED). In the original Gruppentheorie und Quantenmechanik (1928, p. 97) Weyl had written “Eine Abbildung S ...”

This entry was contributed by John Aldrich.

MARGIN OF ERROR. The OED shows the term in use in 1867 in Chambers’s Journal: “For silver coin, the ‘remedy’ or margin of error is fixed at one pennyweight per pound Troy.”

The terms limit of error and error-margin are found in 1889 in “Germicidal Action of Blood” in Journal of the American Medical Association. Here the terms are used in the modern statistical sense of margin of error. [Google print search, James A. Landau]

MARKOV CHAIN. A. A. Markov (1856-1922) introduced chains in 1906 in a paper extending the law of large numbers to sums of dependent variables. (E. Seneta "Markov, Andrei Adreyevich" in Encyclopedia of Statistical Science, 5, 246-249. New York: Wiley.).

The phrase les chaînes de Markoff is found in V. Romanovsky, “Sur les chaînes de Markoff,” C. R. de l'Académie de l'U. R. S. S., 1929, A, n°. 9, p. 203-208. [Thomas Weber]

The term is found in English in 1938 in American Mathematical Monthly, 45, p. 410 [Mark Dunn, JSTOR].

See STOCHASTIC PROCESS.

MARKOV CHAIN MONTE CARLO. This method was proposed for solving the state equations of statistical mechanics by N. Metropolis, A.W. Rosenbluth, M. N. Rosenbluth, A. H. Teller, and E. Teller. "Equations of State Calculations by Fast Computing Machines," Journal of Chemical Physics, 21, 1953, 1087-1092. It was later adopted by statisticians: see W. K. Hastings "Monte Carlo Sampling Methods Using Markov Chains and Their Applications," Biometrika, 57, (1970), 97-109. The name "Markov chain Monte Carlo" seems to have taken off around 1990 when the method first attracted wide attention: see e.g. Charles J. Geyer "Practical Markov Chain Monte Carlo" Statistical Science, 7, (1992), 473-483. See the entry MONTE CARLO.

MARKOV PROCESS. The term comes from the analogy with Markov chain; Markov did not study Markov processes. The name appears in A. Khintchine "Korrelationstheorie der Stationären Stochastischen Prozesse", Math. Ann. 109 (1934), 604-615 although the process had already been investigated by A. N. Kolmogorov "Über die analytischen Methoden in der Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung," Math. Ann. 104, (1931), 415-458. See E. B. Dynkin "Kolmogorov and the Theory of Markov Processes," Annals of Probability, 17, (1989), 822-833.)

The English term appears in 1938 in J. L. Doob "Stochastic Processes With an Integral Valued Parameter," Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 44, p. 102 [Mark Dunn, JSTOR].

See FOKKER-PLANCK EQUATION, MARKOV CHAIN and STOCHASTIC PROCESS.

MARKOV’S INEQUALITY. According to Oscar Sheynin Theory of Probability: A Historical Essay (p. 166) Markov published the result in 1900. It is referred to as Markov’s inequality in L. Bortkiewicz’s Die Iterationen, Ein Beitrag zur Wahrscheinlichkeitstheorie (1917).

The term MARRIAGE THEOREM was introduced by Hermann Weyl in “Almost periodic invariant vector sets in a metric vector space,” Amer. J. Math. 71 (1949), 178-205, according to Konrad Jacobs in Measure and Integral, Academic Press, 1978. The theorem is also called “Hall’s theorem” or “Hall’s marriage theorem” since it was first proved by Philip Hall in 1935: “On Representatives of Subsets,” Journal of the London Mathematical Society, 10, 26-30. [Carlos César de Araújo]

MARTINGALE. The original sense is given in the OED: "a system in gambling which consists in doubling the stake when losing in the hope of eventually recouping oneself." The oldest quotation is from 1815 but the nicest is from 1854: Thackeray in The Newcomes I. 266 "You have not played as yet? Do not do so; above all avoid a martingale if you do."

J. Venn in his Logic of Chance (1888) wrote that the possibility that "by mere persistency [the martingale player] may accumulate any sum of money he pleases, in apparent defiance of all that is meant by luck" has been "a source of perplexity to persons of considerable acutenesss."

There was an early discussion by C. Babbage ("An Examination of Some Questions Connected with Games of Chance" Trans. Royal Soc. Edinburgh, 9 (1821) 153-177).

The martingale of modern probability theory is a mathematical model of a fair game and so is different from the martingale as a gambling system. The connection is a theorem that the martingale system will not change a fair game into an unfair game--an old martingale is a new martingale. J. Ville’s Étude Critique de la Notion de Collectif (1939) begins by discussing old martingale in the context of von Mises’s requirement that with a random sequence a successful gambling system is impossible and goes on to define a (new) martingale as "un jeu équitable."

J. L. Doob’s Stochastic Processes (1954) made the martingale an important chapter of probability theory. In 1940 Doob wrote about “chance variables with the property E” (“Regularity Properties of Certain Families of Chance Variables,” Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 47, 455-486.) See A Conversation with Joe Doob Statistical Science 1997 and R. Mansur Histoire de martingales. Mathématiques et sciences humaines, 2005. [This entry was contributed by John Aldrich.]

MATH and MATHEMATICS. Words of the form math- derive ultimately from the Greek mathematike tekhne meaning "mathematical science," itself derived from manthanein, the ordinary word meaning “to learn.” How the association with a special form of learning came about is considered by T. L. Heath A History of Greek Mathematics, vol. 1 pp. 10-1. Heath describes how the school of Pythagoras distinguished between those who had learnt the theory of knowledge in its most complete form, the mathematicians, and those who knew only the practical rules of conduct. He infers that, “seeing that the Pythagorean philosophy was mainly mathematics, the term might easily become identified with the mathematical subjects as distinct from others.”

The Greek expression went into Latin as the plural noun mathematica. The OED’s oldest quotation (from around 1545) contains the phrase “al the mathematikes in the worlde.” Modern French retains the plural form, les mathématiques, but modern English has fixed on mathematics as a singular noun without a definite article. A passage from 1648 points the way, “Mathematicks..is usually divided into pure and mixed,” though a quotation from Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) follows the older usage, “Navigation, and other Parts of the Mathematicks, useful to those who intend to travel.” (both quotations are from the OED) The first OED quotation to use the modern spelling mathematics is from 1745.

It is clear from the passage from Swift that the scope of ‘mathematics’ has changed in the last three centuries: for its scope in the medieval period and in the Renaissance see the entries QUADRIVIUM and PURE & APPLIED MATHEMATICS.

There have been English words for mathematical and mathematician since the 15th century. The OED finds "mathematicalle" and "mathematicion" in the translation of Higden’s Polychronicon (translated 1432-50): “a man nobly erudite in speculacions mathematicalle” and “Puttenge in to exile many mathematicions.” The Latin words were mathematicalis and mathematicus but there was already a Middle French word, mathematicien. The Latin word mathematicus had other associations. St. Augustine (354-430) wrote in Book 2 of De Genesi ad litteram: "Quapropter bono christiano, sive mathematici, sive quilibet impie divinantium, maxime dicentes vera, cavendi sunt, ne consortio daemoniorum irretiant." A widely-quoted English translation has: "The good Christian should beware of mathematicians, and all those who make empty prophecies. The danger already exists that the mathematicians have made a covenant with the devil to darken the spirit and to confine man in the bonds of Hell." However, mathematicus is more properly translated "astrologer" and a 1982 translation by J. H. Taylor, S. J., in the series Ancient Christian Writers has: "Hence, a devout Christian must avoid astrologers and all impious soothsayers, especially when they tell the truth, for fear of leading his soul into error by consorting with demons and entangling himself with the bonds of such association" [Barry Cipra].

In modern American English the usual shortening of mathematics is math while in British English it is maths, both written without a period. Although these shortened forms only became accepted as words in their own right in the 20th century, the convenience of an abbreviation was felt much earlier. Thus the phrase "Math: books" is found in the writings of Isaac Newton; apparently the colon indicates this is an abbreviation [James A. Landau, Axel Harvey]. The obvious abbreviation for the 19th century periodical Messenger of Mathematics was Mess. of Maths. (found in Phil Trans. A, 184, (1893), p. 1171).

The earliest use of math in OED2 in which it is clear that no period is intended is in 1924 in P. Marks, Plastic Age: "I'm talking about the copying of math problems and the using of trots." However, there are a number of earlier uses in which the word ends a sentence, so that it is unclear whether the writer would have used a period to indicate an abbreviation.

The earliest use of maths in OED2 in which a period is clearly absent is in the Times of Sept. 8, 1959: "Royal Australian Air Force. Education Officers required with Majors in Maths or Physics."

MATHEMATICAL EXPECTATION. See EXPECTATION.

The term MATHEMATICAL INDUCTION was introduced by Augustus de Morgan (1806-1871) in 1838 in the article Induction (Mathematics) which he wrote for the Penny Cyclopedia. De Morgan had suggested the name successive induction in the same article and only used the term mathematical induction incidentally. The expression complete induction attained popularity in Germany after Dedekind used it in a paper of 1887 (Burton, page 440; Boyer, page 404).

See also COMPLETE INDUCTION.

MATHEMATICAL LOGIC is found in 1838 in “A Forensic Essay” in South-West Journal: “It need not be further insisted that these influences are the same in moral as in mathematical reasoning. Without reducing all propositions to formulas, still they can be subjected to mathematical rigor, in the demonstration or the analysis of truth. And in the admission of truths into the mind, for the formation of principle, the nearer each can be brought to the standard of scrutiny, pointed out by mathematical logic, the more safely may those principles be relied upon, and the profound will be all subsequent research.” [Google print search by James A. Landau]

In 1850 in Grammar of arithmetic; or, An analysis of the language of figures and science of numbers Charles Davies wrote: "In explaining the science of Arithmetic, great care should be taken that the analysis of every question and the reasoning by which the principles are proved, be made according to the strictest rules of mathematical logic." [University of Michigan Digital Library].

From the time of Boole’s Mathematical Analysis of Logic (1847) there was a body of work to which the phrase "mathematical logic" might be applied. The OED has a nice quotation from John Venn touching on the improbability of such a study: "What with the logicians who hate mathematics, and the mathematicians who despise logic, a theory of so-called mathematical logic does not find many friends." (Princeton Review, (1880), p. 248.)

Mathematical logic arrived for good in the 1890s. Grattan-Guinness (2000, p. 234) writes that in 1891 Peano launched the Rivista di matematica "with two papers on the subject to which he gave the name that it still carries." The papers were "Principi di logica mathematica" and "Formolo di logica mathematica."

The first course on mathematical logic in Britain was given by Bertrand Russell in Cambridge in the winter of 1901-2. (Grattan-Guinness (2000, p. 331)

This entry was mostly contributed by John Aldrich. See LOGIC.

MATHEMATICAL RIGOR is found in 1685 in Philosophical Transactions 175: “ The true intervals according to Mathematical rigor, are undistinguishable, to the subtilest lense, from equal distances.” [Google print search by James A. Landau]

Leonhard Euler used a term in 1755 in Institutiones calculi differentialis which is rendered "mathematical rigor" in an English translation.

MATHEMATICAL STATISTICS. Mathematische Statistik is found in 1841 in Staats und Privat-Anleihen Schweidnitz by A. L. Rambach. [Google print search by James A. Landau]

Mathematische Statistik is found in 1867 in the title Mathematische Statistik und deren Anwendung auf National-Oekonomie und Versicherungs-Wissenschaft by T. Wittstein (David, 1998).

Mathematical statistics is found in English in 1913 in Statistical Averages: A Methodological Study translated by Warren Milton Persons by Franz Žižek: “However, while mathematical statistics can use the theories of errors and probability as a measure to ascertain typical series and typical means with certainty, a similar precise and objective measure is lacking in non-mathematical statistics, and the decision whether a certain mean or a certain series may be called typical becomes more or less subjective.” [Google print search by James A. Landau]

Mathematical statistics is found in English in 1918 in the title Introduction to Mathematical Statistics by C. J. West (David, 1998).

The term MATRIX was introduced into mathematics by James Joseph Sylvester (1814-1897) in 1850. Matrix was a long-established word with the meaning of “the place from which something else originates.” For Sylvester the “something else” was a determinant of some description:

[...] For this purpose we must commence, not with a square, but with an oblong arrangement of terms consisting, suppose, of m lines and n columns. This will not in itself represent a determinant, but is, as it were, a Matrix out of which we may form various systems of determinants by fixing upon a number p, and selecting at will p lines and p columns, the squares corresponding of pth order.

“Additions to the Articles On a new class of theorems, and On Pascal’s theorem,” Philosophical Magazine, pp. 363-370, 1850. Reprinted in Sylvester’s Collected Mathematical Papers, vol. 1, pp. 145-151, Cambridge (At the University Press), 1904, page 150.

Sylvester used the term on more than one occasion but it was his friend Cayley who treated the “oblong arrangement” as an object in its own right and developed an algebra of matrices in papers of 1855 [“Recherches sur les Matrices ...” Coll Math Papers, II, 216-20] and 1858 [“A Memoir on the Theory of Matrices” Coll Math Papers, II, 475-96]. See Katz (1993) and Kline p. 804.

Charles L. Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) considered Cayley’s use of the word a misuse. In his Elementary Treatise on Determinants (1867) Dodgson preferred the term block to matrix: “I am aware that the word 'Matrix' is already in use to express the very meaning for which I use the word 'Block'; but surely the former word means rather the mould, or form, into which algebraical quantities may be introduced, than an actual assemblage of such quantities...”

There are useful historical notes and references in Appendix I of J. H. M. Wedderburn Lectures on Matrices (1934). Wedderburn (p. 169) points out that the algebra of matrices was re-discovered by Laguerre in 1867 and by Frobenius in 1878. The paper by Frobenius is a very impressive contribution to matrix theory. However the term matrix does not appear in “Ueber lineare Substitutionen und bilineare Formen,” J. reine angew. Math. Vol. 84 (1878) pp.1-63 or in other papers by Frobenius before 1894. It was then that he learnt of Cayley’s work and adopted Cayley’s term.

This entry was contributed by Randy K. Schwartz, Julio González Cabillón, and John Aldrich. A list of matrix and linear algebra terms having entries on this web site is here.

The first works of MATRIX MECHANICS appeared in 1925 and the English term appeared almost immediately. The OED quotes Dirac from 1926: “In Heisenberg’s matrix mechanics it is assumed that the elements of the matrices that represent the dynamical variables determine the frequencies and intensities of the components of the radiation emitted.” From “On the Theory of Quantum Mechanics,” Proc. Royal Soc. A. 112, p. 666. The matrix formalism is explicit in M. Born and P. Jordan “Zur Quantenmechanik” Zeitschrift für Physik, 34, (1925), 858-888. This followed earlier work by Heisenberg. [There are English translations of the papers in B. L. van der Waerden (editor) Sources of Quantum Mechanics (Dover Publications, 1968.)] See also the entry EIGENVALUE.

MATROID. In a effort to axiomatize the notion of "independence" that arises in graph theory and in vector spaces theory, Hassler Whitney coined the term "matroid" and introduced it in his fundamental paper On the abstract properties of linear independence, Amer. J. Math. 57 (1935) 509-533. The choice of the name arose because he took as an initial model the finite sets of linearly independent column vectors of a matrix over a field. In his paper Whitney gave several equivalent characterizations of a matroid, but the general idea is that of a finite set endowed with a "independence structure" (just as a topological space is a set endowed with a "closeness structure"). Extensions to infinite sets and additional contributions were made by Saunders Mac Lane (1936), R. Rado (1942), W. T. Tutte (1961) and many others. [Carlos César de Araújo]

MAXIMAL (of an element in an ordered or partially ordered set) is found in 1896 in Annals of Math. vol. 11, p. 169 [Mark Dunn, JSTOR].

MAXIMUM and MINIMUM. These are classical Latin words. Maximum is the neuter of maximus greatest, superlative of magnus and minimum is the neuter of minimus smallest. Mathematicians writing in Latin used these words.

Finding maxima and minima was one of the topics in Leibniz’s first publication on differential calculus, Nova Methodus pro Maximis et Minimis, itemque Tangentibus qua nec Fractas nec Irrationales Quantitates Moratur, et Singulare pro illi Calculi Genus published in 1684 in Acta Eruditorum, 3, (1684) 467-473.

In English the words are found in 1743 in W. Emerson, Doctrine of Fluxions: “When a Quantity is required to be the greatest or least possible, under certain Conditions, it is called a Maximum or Minimum.” [Mark Dunn]

MAXIMUM LIKELIHOOD. The method has been traced back to Daniel Bernoulli’s “Diiudicatio maxime probabilis plurium observationem discrepantium atque verisimillima inductio inde formanda.” Acta Acad. Sci. Imp. Petrop., 1777 (1778), 1, 3-23. This has been translated into English by C. G. Allen as “The most probable choice between several discrepant observations and the formation therefrom of the most likely induction” and appears, with a note by M. G. Kendall, as “Daniel Bernoulli on Maximum Likelihood,” in Biometrika, (1961), 48, 1-18. However the modern use of the method dates from the work of R. A. Fisher. Fisher introduced the term maximum likelihood in his “On the Mathematical Foundations of Theoretical Statistics” (Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. Ser. A. 222, (1922), p. 323.) Previously he had used two terms. In his “On the ‘Probable Error’ of a Coefficient of Correlation Deduced from a Small Sample” (Metron, 1, (1921), 3-32 the optimum is the value that maximizes the “likelihood.” However Fisher’s use of the method pre-dated the elaboration of his ideas about likelihood and the absolute criterion of 1912 is mathematically the same as maximum likelihood: “On an Absolute Criterion for Fitting Frequency Curves” Messenger of Mathematics, 1912, 41, 155-160.

For more on the history of maximum likelihood before and after Fisher see: A. Hald “On the History of Maximum Likelihood in Relation to Inverse Probability and Least Squares” Statistical Science 14, (1999), 214-222; J. Aldrich “R. A. Fisher and the Making of Maximum Likelihood 1912–1922” Statistical Science 12 (1997), 162–176; S. M. Stigler “ The Epic Story of Maximum Likelihood” Statistical Science 22 (2007), 598–620.

This entry was contributed by John Aldrich. See LIKELIHOOD.

MAXWELL DISTRIBUTION. J. C. Maxwell gave this distribution as the solution of the problem on the distribution of velocities of molecules in an ideal gas in his "Illustrations of the Dynamical Theory of Gases," Philosophical Magazine, 19, (1860), 19-32.

MEAN. Sir Thomas Heath in his History of Greek Mathematics, volume 1 (1921, p. 85) writes that Pythagoras "discovered the dependence of musical intervals on numerical ratios, and the theory of means was developed very early in his school with reference to the theory of music and arithmetic. ... [There] were three means, the arithmetic, the geometric and the subcontrary." The last was later renamed the 'harmonic.' For more on music and means, see the entry HARMONIC MEAN.

Mean occurs in English in the sense of a geometric mean in a Middle English manuscript of circa 1450 known as The Art of Numbering: "Lede the rote of o quadrat into the rote of the oþer quadrat, and þan wolle þe meene shew" [Mark Dunn].

In 1571, A geometrical practise named Pantometria by Thomas Digges (1546?-1595) has: "When foure magnitudes are...in continual proportion, the first and the fourth are the extremes, and the second and thirde the meanes" [OED].

Mean is often used as an abbreviation for arithmetic mean. This is not a new practice: see e.g. Thomas Simpson’s On the Advantage of Taking the Mean of a Number of Observations Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 1755.

In statistical mechanics, probability and statistics mean has often meant expectation; e.g. the "mean velocity" of molecules in J. Clerk Maxwell’s "On the Dynamical Theory of Gases (Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 157, (1867) p. 64).

Mean is one of the most common terms in Mathematics. As a noun it appears in such constructions as Hölder mean and Cesàro mean and as an adjective in such constructions as mean square error.

See ARITHMETIC MEAN, AVERAGE, CESÀRO MEAN, EXPECTATION, GEOMETRIC MEAN, HARMONIC MEAN, HÖLDER MEAN and WEIGHT, for the weighted mean. See also Symbols in Statistics on the Symbols in Probability and Statistics page.

MEAN CURVATURE appears in 1840 in J. R. Young, Mathematical Dissertations (1841). (The preface is dated Nov. 25, 1840.) According to James A. Landau, who provided this citation, Young specialized in introducing recent French developments in geometry (particularly those of Monge) to English-speaking readers, so that it is possible that this is the first appearance of "mean curvature" in English.

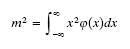

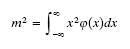

MEAN ERROR was a standard term in the 19th century theory of errors. Gauss introduced it in Theoria combinationis observationum erroribus minimis obnoxiae (Theory of the combination of observations least subject to error) (1821, p. 7), in connection with the integral

where x is an error and φ its density function: "quantitatem m vocabimus errorem medium metuendum, sive simpliciter errorem medium ..." [We will call m the mean error to be feared, or simply the mean error ...]. Gauss adopted a decision theory approach, arguing that an error (of an observation, or quantity derived from observations) generates a loss ("iactura") and of the many possible loss functions the quadratic loss function is simplest. The expected loss is m2. See the entry on DECISION THEORY.

The German term was "die mittlere Fehler": see e.g. F. R. Helmert Die Ausgleichsrechnung nach der Methode der kleinsten Quadrate (1872, p. 12). It was used with the same flexibility--or ambiguity--as the later term standard deviation, which replaced it in some uses.

In Higher Mathematics for Students of Chemistry and Physics (1912), J. W. Mellor writes:

In Germany, the favourite method is to employ the mean error, which is defined as the error whose square is the mean of the squares of all the errors, or the "error which, if it alone were assumed in all the observations indifferently, would give the same sum of the squares of the errors as that which actually exists." ...The mean error must not be confused with the "mean of the errors," or, as it is sometimes called, the average error, another standard of comparison defined as the mean of all the errors regardless of sign.

Mellor’s footnote testifies to the confusion in terminology, "Some writers call our "average error" the "mean error," and our "mean error" the "error of mean square". The latter usage can be found in G. B Airy’s 1861 book, On the Algebraical and Numerical Theory of Errors of Observation and the Combination of Observations. [James A. Landau]

This entry was contributed by John Aldrich. See STANDARD DEVIATION.

MEANS. According to Smith (vol. 2, page 483), "The terms 'means,' 'antecedent,' and 'consequent' are due to the Latin translators of Euclid."

MEAN SQUARE is found in 1838 in An Essay on Probabilities, and Their Application to Life Contingencies and Insurance Offices by Augustus De Morgan. [Google print search]

The term MEAN SQUARE DEVIATION (apparently meaning variance) appears in a paper published by Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher in 1920 A Mathematical Examination of the Methods of Determining the Accuracy of an Observation by the Mean Error, and by the Mean Square Error. [James A. Landau].

C. B. Davenport and Marian E. Hubbard in “Studies in the Evolution of Pecten: IV. Ray Variability in Pecten Varius” reprinted from The Journal of Experimental Zoology in 1904 has: “The whole matter of the proper measure of variability is a complex one. Some years ago Verschaffelt ('94), Pearson ('96) and one of us in a note to Brewster’s ('97) paper independently proposed that the coefficient of variability be employed; that is, the ratio of the index of variability (square root of mean square deviation) to the average.” [Google print search by James A. Landau]

MEAN VALUE THEOREM. “Theorem of mean value” is found in 1889 in Life of William Rowan Hamilton by Robert Perceval Graves.

Mean value theorem is found in 1894 in Proceedings of the Edinburgh Mathematical Society vol. 12. [Google print search by James A. Landau]

The term MEASURABLE FUNCTION was used by Arnaud Denjoy (1884-1974) (Kramer, p. 648).

Measurable function is found in 1907 in The Theory of Functions of a Real Variable and the Theory of Fourier’s Series by E. W. Hobson. [Google print search by James A. Landau]

MEASURE. Émile Borel wrote in 1912:

La définition de la mesure des ensembles linéaires bien définis m'est entièrement due.” (The definition of the measure of well defined linear sets, is entirely due to me.) [Udai Venedem].

Borel introduced the concept in his book on complex analysis, Leçons sur la théorie des fonctions (1898), and Henri Lebesgue used it to construct the LEBESGUE INTEGRAL; he announced the integral in his “Sur une généralisation de l’intégral défini,” Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences, 132, (1901) 1025-1028. See T. Hawkins Lebesgue’s Theory of Integration: Its Origins and Development and the Encyclopaedia of Mathematics entry Measure.

The subject attracted many workers and soon there was a sizeable literature on measure and related concepts in Italian, German and English. Here are some examples.

Giuseppe Vitali Sul problema della misura dei gruppi di punti di una retta Bologna: Tip. Gamberini e Parmeggiani (1905).

Edward B. Van Vleck “On Non-Measurable Sets of Points, with an Example,” Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 9, (1908): “Lebesgue’s theory of integration is based on the notion of the measure of a set of points, a notion introduced by BOREL and subsequently refined by LEBESGUE himself.”

Nikolai Luzin “Sur les propriétês des fonctions mesurables,” Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences, 154 (1912), 1688-1690.

Constantin Carathéodory “Über das lineare Maß von Punktmengen—eine Verallgemeinerung des Langenbegriffs,” Nachrichten Ges. Wiss. Gottingen, 1914.

MECHANICAL QUADRATURE. See the entry QUADRATURE.

MEDIAN (in statistics). Valeur médiane was used by Antoine A. Cournot in 1843 in Exposition de la Théorie des Chances et des Probabilités (pp. 119-20) (David, 1998).

Median was used in English by Francis Galton in Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science [Tables and discussion of range in height, weight and strength] in 1881: "The Median, in height, weight, or any other attribute, is the value which is exceeded by one-half of an infinitely large group, and which the other half fall short of." [OED].

See also MEAN and MODE.

MEDIAN (of a triangle). Median line is found in 1807 in Elements of geometry: including plane, solid and spherical geometry by George Washington Hull. [Google print search by James A. Landau]

Median is found in 1876 in Lessons in elementary mechanics. Introductory to the study of physical science by Sir Philip Magnus, with emendations and introduction by Prof. DeVolson Wood: "In the same way it may be shown that the centre of gravity of the triangle is in the median CE (fig. 109). Hence the centre of gravity of the triangle is at G, where the two medians intersect" [University of Michigan Digital Library].

MEDIATE is found in 1912 in Principia Mathematica vol 2 by Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell. [Google print search by James A. Landau]

MENTAL ARITHMETIC is found in 1765 in H. Brooke, Fool of Quality, vol. I., p. 260: "I cast up, in a pleasing kind of mental arithmetic, how much my weekly twenty guineas would amount to at the year’s end" [Mark Dunn].

MEROMORPHIC FUNCTION. See the entry HOLOMORPHIC FUNCTION and MEROMORPHIC FUNCTION.

MERSENNE NUMBER is found in É. Lucas, Récréations Mathématiques, tome II, Note II, "Sur les nombres de Fermat et de Mersenne" (1883).

Mersenne’s number is found in English in the title "Mersenne’s numbers" by W. W. Rouse Ball in Messenger of Mathematics in 1891.

Mersenne number is found in English in the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica: "Similar difficulties are encountered when we examine Mersenne’s numbers, which are those of the form 2p - 1, with p a prime; the known cases for which a Mersenne number is prime correspond to p = 2, 3, 5, 7, 13, 17, 19, 31, 61" [OED].

Mersenne prime is found in English in 1914 in the Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, vol. 20, October 1913 to July 1914. Page 531 has a letter by one R. E. Powers stating that 2107 – 1 is prime. The letter is entitled “A MERSENNE PRIME.” [Google print search by James A. Landau]

MESSENGER PROBLEM. In 1930, Karl Menger (1902-1985) mentioned the messenger problem, referring to the problem of finding the shortest Hamiltonian path, according to an Internet web page.

META-ANALYSIS. The term was introduced by Gene V. Glass (1976) "Primary, Secondary, and Meta-analysis of Research," Educational Researcher, 5, 3-8: "I use [the term] to refer to the statistical analysis of a large collection of results from individual studies for the purpose of integrating the findings."

Meta-analysis has become a very active area of statistical research. Naturally, pioneers have been identified, including Karl Pearson, "Report on Certain Enteric Fever Inoculation Statistics," British Medical Journal, 3, (1904) 1243-1246, R. A Fisher "The Combination of Probabilities from Tests of Significance," §21.1 of Statistical Methods for Research Workers (4th edition 1932) and F. Yates & W. G. Cochran "The Analysis of Groups of Experiments," Journal of Agricultural Science, 28, (1938), 556-580.

METABELIAN GROUP is found in 1900 in Summarized proceedings . . . and a directory of members The American Association for the Advancement of Science. [Google print search by James A. Landau]

METAMATHEMATICS. Metamathematischen is found in 1828 in Sämmtliche Werke, Volume 60. [Google print search]

According to John Aldrich, the term metamathematics goes back to the 1870s where it was used as a pejorative (intending to put it in the same light as metaphysics) in discussions of non-Euclidean geometries.

Metamathematics is found in 1879 in A vocabulary of the Philosophical Sciences by Charles Porterfield Krauth, giving the definition “METAMATHEMATICS, philosophy of mathematics.”

Also in 1879 the term is found in The Athenaeum: “for the last ten years the only utterances on philosophic themes which have come home to Englishmen have been made by popular expositors of modern physics, eloquent biologists, or ingenious professors of meta-mathematics.” [Google print search by James A. Landau]

In the 1890 Funk & Wagnalls Dictionary the word is defined as “The philosophy or metaphysics of mathematics.”

The word was first used in its modern sense by David Hilbert (1862-1943) in a 1922 lecture and it appears, as metamathematik, in 1923 in "Die logischen Grundlagen der Mathematik" Math. Ann. 88. p. 153. [Michael Detlefsen, Carlos César de Araújo]

The METHOD OF EXHAUSTION for finding areas was introduced by Eudoxus and used by Archimedes.

Gregorius a Sancto Vincentio (or Gregory St. Vincent) was “probably the first to use the word exhaurire in a geometrical sense” (Cajori 1919). Vincentio used the term in 1647, according to A Concise History of Mathematics by Dirk J. Struik, third edition.

Method of exhaustions appears in English in 1685 in Treat. Algebra by John Wallis: “It will be necessary to premise somewhat concerning (what is wont to be called) the Method of Exhaustions” [OED].

See Encyclopaedia of Mathematics and MacTutor A history of the calculus.

The term METHOD OF LEAST SQUARES was coined by Adrien Marie Legendre (1752-1833), appearing in Sur la Méthode des moindres quarrés [On the method of least squares], the title of an appendix to Nouvelles méthodes pour la détermination des orbites des comètes (1805). The appendix is dated March 6, 1805. A much more sophisticated treatment appeared soon after: Gauss’s Theoria Motus Corporum Coelestium in Sectionibus Conicis Solem Ambientum (The Theory of the Motion of Heavenly Bodies moving around the Sun in Conic Sections) of 1809. There was a dispute about priority for Gauss claimed he had been using the method since 1795.

Method of least squares is found in English in 1825 in the title "On the Method of Least Squares" by J. Ivory in Philosophical Magazine, 65, 3-10.

This entry was contribugted by James A. Landau, based on David (1995). See the entries ERROR, GAUSSIAN, GAUSS-MARKOV THEOREM.

The term METRIC SPACE is due to Felix Hausdorff (1869-1942) who gave axioms for the metrischer Raum in his Grundzüge der Mengenlehre (1914, pp. 211-2). Hausdorff’s axioms governing "die Entfernung" were based on Fréchet’s treatment of "l’écart" in "Sur quelques points du calcul fonctionnel," Rendiconti del Circolo matematico di Palermo, 22, (1906) pp. 1-67.

Metric space is found in English in E. W. Chittenden; A. D. Pitcher "On the Theory of Developments of an Abstract Class in Relation to the Calcul Fonctionnel," Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 20, (1919), 213-233. (JSTOR)

Metrizable is a translation of the German metrisierbar found in P. Urysohn “Über die Metrisation der kompakten topologischen Räume,” in Math. Ann., 92, (1924) , p. 275. The English word is found in E. W. Chittenden “On the Metrization problem and Related Problems in the Theory of Abstract Sets,” Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (1927) 33, pp. 13-34: “It is therefore of interest to formulate the conditions that a space be metrizable in terms of continuous functions.” (p. 25). (Information from the OED.)

METRIC SYSTEM. Noah Webster’s 1806 dictionary has the heading "New French Weights and Measures."

Metric system is found in 1814 in A New Mathematical and Philosophical Dictionary by Peter Barlow. The article on “Measure” table on the third page has a heading “METRE SYSTEM” and has entries under that heading for “Are, a Square Decametre”, “Decare”, and “Hecatare”. The following page column 1 reads “Various attempts have been made by different mathematicians to find a perpetual standard of measure, which might be referred to at any time and under any circumstance, supposing the standard in present use to be lost. The above metric system of the French is founded on this principle…” The fourth page of the article on “Weight” reads [bottom of first column] “We have made a slight mention in the preceding part of this article of the French system of weights, as deduced from the metric system of measures; and although, as we have observed above, this system is reported to have been abandoned by the French government; yet the ingenuity employed in establishing it, and the simplicity of it, when once accurately determined, render it necessary for us to give the reader an idea of its original construction.”

Decimal system appears in 1819 in The Cyclopćdia; or Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature by Abraham Rees.

In 1821 John Quincy Adams used the terms French system and French metrology.

Webster’s dictionary of 1828 refers to French measure.

Gram is found in English in Aug. 1797 in Nicholson’s Journal where it is spelled "gramme." Kilogram and liter are found in English in Aug. 1797 in Journal of Natural Philosophy. Kilometer, milliliter, millimeter, and milligram are found in English in Noah Webster’s 1806 A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, although kilometer is spelled "chiliometer."

Metric ton is found in 1864 in Journal of the Statistical Society of London.

For statistical purposes, it is convenient to take one unit, the metric ton – a cubic meter of water, and nearly equal to the English ton, to express the imports and exports, and the quantities of all articles sold by weight. This would facilitate comparison. The quantities sold by volume, such as wheat, fish, oil, wine, and spirits, might also be expressed by one unit---the metric tun, the bulk of water weighing a metric ton. The qualities and prices of some articles, such as wheat and spirits, are regulated by the weight of equal bulks, or by the specific gravity, which is easily pressed as it is the weight of a metric tun of the stuff, when a metric ton is taken for unity.

[Google print search by James A. Landau]

Micron (one millionth of a meter) was coined by Johann Benedict Listing (1808-1882), according to Breitenberger (1999). The OED2 shows a use of the word in French in 1880 in Procès-Verbaux des Séances du Comité Internat. des Poids et Mesures 1879.

MIDCENTER. See the entry CIRCUMCENTER, CIRCUMCIRCLE, EXCENTER, EXCIRCLE, INCENTER, INCIRCLE, MIDCIRCLE.

MILLER-RABIN TEST is found in H. W. Lenstra, Jr. "Primality testing," Number theory and computers, Studyweek, Math. Cent. Amsterdam 1980, and in Louis Monier, "Evaluation and comparison of two efficient probabilistic primality testing algorithms," Theor. Comput. Sci., 12 (1980).

Related terms are found in H. W. Lenstra, Jr., "Miller’s primality test," Inf. Process. Lett. 8 (1979) and Tore Herlestam, "A note on Rabin’s probabilistic primality test," BIT, Nord. Tidskr. Informationsbehandling 20 (1980).

MILLIARD. Gulielmus Budaeus (1467-1540) used the term in his De Asse et Partibus eius Libri V. In the Paris edition of 1532, the following appears: "hoc est denas myriadu myriadas, quod vno verbo nostrates abaci studiosi Milliartu appellat, quasi millionu millione" (Smith vol. 2, page 85).

MILLION, BILLION, etc. The following is taken from Smith (vol. 2, pages 80-86):

One of the most striking features of ancient arithmetic is the rarity of large numbers. There are exceptions, as in some of the Hindu traditions of Buddha’s skill with numbers, in the records on some of the Babylonian tablets, and in the Sand Reckoner of Archimedes with its number system extending to 1063, but these are all cases in which the élite of the mathematical world were concerned; the people, and indeed the substantial mathematicians in most cases, had little need for or interest in numbers of any considerable size.Million appears in the King James Bible: "And they blessed Rebekah, and said unto her, Thou art our sister, be thou the mother of thousands of millions, and let thy seed possess the gate of those which hate them" (Gen. 24: 60). (This is translated "many millions" in the Living Bible.)The word "million," for example, is not found before the 13th century, and seems to have come into use in England even later. William Langland (c. 1334-c. 1400), in Piers Plowman, says,

Coueyte not his goodes

For millions of moneye,but Maximus Planudes (c. 1340) seems to have been among the first of the mathematicians to use the word. By the 15th century it was known to the Italian arithmeticians, for Ghaligai (1521; 1552 ed., fol. 3) relates that "Maestro Paulo da Pisa" read the seventh order as millions. It first appeared in a printed work in the Treviso arithmetic of 1478. Thereafter it found place in the works of most of the important popular Italian writers, such as Borghi (1484), Pellos (1492), and Pacioli (1494), but outside of Italy and France it was for a long time used only sparingly. Thus, Gemma Frisius (1540) used "thousand thousand" in his Latin editions, which were published in the North, while in the Italian translation (1567) the word millioni appears. Similarly, Clavius carried his German ideas along with him when he went to Rome, and when (1583) he wished to speak of a thousand thousand he almost apologized for using "million," referring to it as an Italian form which needed some explanation.

In Spain the word cuento was early used for 106, the word million being reserved for 1012. When the latter word was adopted by mathematicians, it was slow in coming into general use.

France early took the word "million" from Italy, as when Chuquet (1484) used it, being followed by De la Roche (1520), after which it became fairly common.

The conservative Latin writers of the 16th century were very slow in adopting the word. Even Tonstall (1522), who followed such eminent Italian writers as Pacioli, did not commonly use it. He seems to have been influenced by the fact that the Romans had no use for large numbers; or by the fact that, for common purposes, it sufficed to say "thousand thousand" as had been done for many generations. He simply mentions the word as a piece of foreign slang to be avoided. Other Latin writers were content to say "thousand thousand."

The German writers were equally slow in abandoning "thousand thousand" for "million," most of the writers of the 16th century preferring the older form. The Dutch were even more conservative, continuing the old form later than the writers in the neighboring countries. Indeed, for the ordinary needs of business in the 16th century, the word "million" was a luxury rather than a necessity.

England adopted the Italian word more readily than the other countries, probably owing to the influence of Recorde (c. 1542). It is interesting to see that Poland was also among the first to recognize its value, the word appearing in the arithmetic of Klos in 1538.

Until the World War of 1914-1918 taught the world to think in billions there was not much need for number names beyond millions. Numbers could be expressed in figures, and an astronomer could write a number like 9.15 · 107, or 2.5 · 1020, without caring anything about the name. Because of this fact there was no uniformity in the use of the word "billion." It meant a thousand million (109) in the United States and a million million (1012) in England, while France commonly used milliard for 109, with billion as an alternative term.

Historically the billion first appears as 1012, as the English use the term. It is found in this sense in Chuquet’s number scheme (1484), and this scheme was used by De la Roche (1520), who simply copied parts of Chuquet’s unpublished manuscript, but it was not common in France at this time, and it was not until the latter part of the 17th century that it found place in Germany. Although Italy had been the first country to make use of the word "million," it was slow in adopting the word "billion." Even in the 1592 edition of Tartaglia’s arithmetic the word does not appear. Cataldi (1602) was the first Italian writer of any prominence to use the term, but he suggested it as a curiosity rather than a word of practical value. About the same time the term appeared in Holland, but it was not often recognized by writers there or elsewhere until the 18th century, and even then it was not used outside the schools. Even as good an arithmetician as Guido Grandi (1671-1742) preferred to speak of a million million rather than use the shorter term.

The French use of milliard, for 109, with billion as an alternative, is relatively late. The word appears at least as early as the beginning of the 16th century as the equivalent both of 109 and of 1012, the latter being the billion of England today. By the 17th century, however, it was used in Holland to mean 109, and no doubt it was about this time that the usage began to change in France.

As to the American usage, taking a billion to mean a thousand million and running the subsequent names by thousands, it should be said that this is due in part to French influence after the Revolutionary War, although our earliest native American arithmetic, the Greenwood book of 1729, gave the billion as 109, the trillion as 1012, and so on. Names for large numbers were the fashion in early days, Pike’s well-known arithmetic (1788), for example, proceeding to duodecillions before taking up addition.

Million was also used by Shakespeare a number of times.

The number 200,000,000 appears in the Living Bible in Rev. 9:16. It is translated as "two hundred thousand thousand" in the King James version (1611), "twice ten thousand times ten thousand" in Darby (1890) and RSV (1946), "two myriads of myriads" in Young’s Literal Translation (1898), and "two hundred million" in the New International Version (1973).

Billion first occurs, with the meaning 1012, in French in 1484 in Le Triparty en la Science des Nombres by Nicolas Chuquet (1445?-1500?). He used the words byllion, tryllion, quadrillion, quyllion, sixlion, septyllion, ottyllion, and nonyllion. A translation has: "The first dot indicates million, the second dot billion, the third dot trillion, the fourth dot quadrillion...and so on as far as one may wish to go."

The OED2 has:

The name [billion] appears not to have been adopted in Eng. before the end of the 17th c. .... Subsequently the application of the word was changed by French arithmeticians, figures being divided in numeration into groups of threes, instead of sixes, so that F. billion, trillion, denoted not the second and third powers of a million, but a thousand millions and a thousand thousand millions. In the 19th century, the U.S. adopted the French convention, but Britain retained the original and etymological use (to which France reverted in 1948). Since 1951 the U.S. value, a thousand millions, has been increasingly used in Britain, especially in technical writing and, more recently, in journalism; but the older sense "a million millions" is still common.]Decillion occurs in English in 1847.

Centillionen is found in German in 1740 in Biblischer Geographus by Johann J. Schmidt: “Was wirds nun helfen, die Zahlen so zu häufen, daß man sie mit Centillionen aussprechen könnte; wer wird denn einen Verstand hergeben, der sie begreift?” [Ivan Panchenko, Google print search]

Centilion (spelled this way) is found in English in 1754 in The Gentleman’s Magazine:

Your correspondent Mr Holliday has given us an account of one Jededia Buxton (See Vol. xxiii. p. 557) whose arithmetical computations discover a strength of memory scarce to be parallelled, and chance has lately thrown in my way a journeyman carpenter, who is scarce less remarkable, as an original character, tho’ it is of a different kind. This man, who knows no language but his own, except that by some accident he learned the Latin adverbs of quantity, has contrived denominations, by which he can enumerate a series of six hundred and six figures, and distinguish every scale of the gradation; he proceeds by millions, billions, trillions, quadrillions, quinquillians, sexillions, octillions, &c. to novinonagillions, and centilions.

The above letter also appears in 1754 in The Scots Magazine, where the spellings centillions and quinquillions are used. [Ivan Panchenko]

Centillion is found in English in 1863 in The Normal: or, Methods of Teaching the Common Branches, Orthoepy, Orthography, Grammar, Geography, Arithmetic and Elocution by Alfred Holbrook, which has the following:

Names of the periods. - 1st, Units. 2d, Thousands. 3d, Millions. 4th, Billions. 5th, Trillions. 6th, Quadrillions. 7th, Quintillions. 8th, Sextillions. 9th, Septillions. 10th, Octillions. 11th, Nonillions. 12th, Decillions. 13th, Undecillions. 14th, Duodecillions. 15th, Tridecillions. 16th, Quadrodecillions. 17th, Quindecillions. 18th, Sexdecillions. 19th, Septodecillions. 20th, Octodecillions. 21st, Nonodecillions. 22d, Vigintillions. 23d, Unvingintillions. 24th, Duo-vingintillions, etc. 32d, Trigintillions. 42d, Quadrogintillions. 52d, Quingintillions. 62d, Sexagintillions. 72d, Septuagintillions. 82d, Octogintillions. 92d, Ninogintillions. 102d, Centillions. 103d, Uncentillions. 104th, Duocentillions, etc. 202d, Duocentillions, etc. 1002d, Millillions, etc.

The term MINIMAL BASIS is due to Felix Klein, according to Harkness and Morley in A Treatise on the Theory of Functions.

MINIMAX (in geometry). In the sense of a saddle point of a surface or similar concept in higher dimensions, Poincaré wrote in 1899 in Méthodes Nouvelles de la Mécanique Céleste III. 246: "J'appelle minimax, à l'exemple des Anglais, un point pour lequel..."

Alan M. Hughes, Associate Editor of the OED, reports that, despite Poincare’s comment, no earlier English usage has been traced.

Mark Dunn writes that the earliest English use appears to be in 1917 in Trans. American Math. Soc., vol. 18, p. 240. Most later examples of this meaning in English refer to this 1917 article as though it is the first use.

MINIMAX (in game theory). In 1928 J. von Neumann wrote in " Zur Theorie der Gesellschaftsspiele" Mathematische Annalen, 100, (p. 307) the heading "Beweis des Satzes Max Min = Min Max" [OED].

Min-max is found in English in 1944 in J. Von Neumann & Morgenstern, Theory of Games: "A slightly more general form of this Min-Max problem arises in another question of mathematical economics" [OED].

Minimax solution to a statistical decision problem appears in 1947 in Wald’s "Foundations of a General Theory of Sequential Decision Functions," Econometrica, 15, 279-313 but the concept had appeared in his 1939 paper under the guise of the "best estimate."

Minimax estimate appears in Hodges & Lehmann’s "Some Problems in Minimax Point Estimation", Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 21, (1950), 182-197 [John Aldrich, based on David (2001)].

Maximin is dated 1951 in MWCD10.

See DECISION THEORY and THEORY of GAMES.

MINIMUM CHI-SQUARED. After Karl Pearson introduced the χ2 goodness of fit test in 1900 several authors tried basing estimation on χ2. E. Slutsky’s (1913) "On the Criterion of Goodness of Fit of the Regression Lines and on the Best Method of Fitting them to the Data," Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 77, 78-84 and F. L. Engledow & G. U. Yule’s (1914) "The Determination of the Best Value of the Coupling-ratio from a Given Set of Data," Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 17, 436-440 seem to have been the first. However these papers were less noticed than Kirstine Smith’s "On the 'Best' Values of the Constants in Frequency Distributions," Biometrika, 11, (1916), 262-276. Smith used the phrase "minimum χ2" but only in tables where brevity was necessary. R. A. Fisher read Smith and he was the writer who did most to keep minimum χ2 in view, for he often compared it with his own maximum likelihood: see e.g. "On the Mathematical Foundations of Theoretical Statistics", Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. Ser. A. 222, (1922) p. 357.

(Based on A. W. F. Edwards "Three Early Papers on Efficient Parametric Estimation," Statistical Science, 12, (1997), 35-38.)

See CHI SQUARE, MAXIMUM LIKELIHOOD.

MINKOWSKI’S INEQUALITY was given in Hermann Minkowski’s Geometrie der Zahlen (1896, pp. 115-7). It is discussed in Inequalities by G. H. Hardy, J. E. Littlewood and G. Polya (1934).

The term MINOR was apparently coined by James Joseph Sylvester, who wrote in Philos. Mag. Nov. 1850:

Now conceive any one line and any one column to be struck out, we get ... a square, one term less in breadth and depth than the original square; and by varying in every possible manner the selection of the line and column excluded, we obtain, supposing the original square to consist of n lines and n columns, n2 such minor squares, each of which will represent what I term a First Minor Determinant relative to the principal or complete determinant. Now suppose two lines and two columns struck out from the original square ... These constitute what I term a system of Second Minor Determinants; and ... we can form a system of rth minor determinants by the exclusion of r lines and r columns.Sylvester also used minor as a noun in the same article: "The whole of a system of rth minors being zero" and "We shall have only to deal with a system of first minors" (OED).

MINUEND is an abbreviation of the Latin numerus minuendus (number to be diminished), which was used by Johannes Hispalensis (c. 1140) (Smith vol. 2, page 96).

In English, minuend was used in 1706 by William Jones in Synopsis palmariorum matheseos, or a new introduction to the mathematics [OED].

MINUS. See PLUS.

MINUS SIGN. Negative sign appears in 1668 in T. Brancker, Introd. Algebra: "The Sign for Subtraction is - i.e. Minus, or the Negative Sign.

Minus sign is found in 1825 in History of the Political and Military Transactions in India during the Administration of the Marquess of Hastings 1813-1823 by Henry T. Prinsep.

MIXED NUMBER appears in English in 1542 in The Ground of Artes by Robert Recorde: "mixt numbers (that is whole numbers with fractions)" [OED].

MÖBIUS STRIP. In 1893 A Treatise on the Theory of Functions by James Harkness and Frank Morley has “surfaces such as those of Möbius.” [Google print search by James A. Landau]

Möbius’ strip appears in 1904 in E. R. Hedrick, translation of Goursat’s Course in Mathematical Analysis [OED].

August Möbius described the object in "Ueber die Bestimmung des Inhaltes eines Polyëders" (1865). See Gesammelte Werke II, p. 484. According to Grattan-Guinness (1997, p. 404), Johann Benedict Listing also found the construction in 1858; Listing published it in 1861.

MODE was coined by Karl Pearson (1857-1936). He used the term in 1895 in "Contributions to the Mathematical Theory of Evolution. II. Skew Variation in Homogeneous Material," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Ser. A, 186, 343-414: "I have found it convenient to use the term mode for the abscissa corresponding to the ordinate of maximum frequency. Thus the "mean," the "mode," and the "median" have all distinct characters." (p. 345)

See also MEAN and MEDIAN.

MODULAR ARITHMETIC. The subject of modular arithmetic originated in Gauss' Disquisitiones arithmeticae of 1801.

Modular arithmetic is found in English in 1941 in Fund. Mathematics by D. Harkin in the heading Finite modular arithmetic. [OED]

See MODULUS, MODULO and MOD.

MODULAR CURVE appears in 1878 in J. J. S. Smith, "On the modular curves," Rep. Brit. Ass.

The term MODULAR EQUATION was introduced by Jacobi [Encyclopaedia Britannica (1902), article "Infinitesimal Calculus"; Smith (1906)].

The term équations modulaires appears on January 12, 1828, in a letter written by Jacobi to Legendre [Emili Bifet].

Modular equation is found in 1836 in A Treatise on the Calculus of Functions by Augustus De Morgan. [Google print search by James A. Landau]

MODULAR FORM occurs in the heading "Definite Modular Forms" in "Definite Forms in a Finite Field," Leonard Eugene Dickson, Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, Vol. 10, No. 1. (Jan., 1909).

MODULAR FUNCTION. According to the DSB, Christoph Gudermann (1798-1852) called elliptical functions “Modularfunctionen.” A Google print search finds the term in use in 1844 by Christoph Gudermann in “Theorie der Modular-Functionen und der Modular-Integrale.” Besonders abgedr. aus Crelle’s Journ. für d. reine u. angewandte Math. [James A. Landau]

Joseph Alfred Serret (1819-1885) defined modular functions in 1866 in "Mémoire sur la théorie des congruences suivant un module premier et suivant une fonction modulaire irréductible," Mémoires de l'Acad.: "La fonction irréductible qui intervient ici, joue le rôle de module, et je lui donne en conséquence le nom de fonction modulaire" [Udai Venedem].

Richard Dedekind (1831-1916) used the term elliptic modular function in "Schreiben an Herrn Borchardt ueber die Theorie der elliptischen Modulfunktionen," J. reine angew. Math. 83 (1877), 265-292. According to Klein, this was the origin of the general name modular functions for functions with this or similar invariance [William C. Waterhouse].

MODULE. A JSTOR search found the English term in E. T. Bell’s “Successive Generalizations in the Theory of Numbers,” American Mathematical Monthly, 34, (1927), 55-75. Bell was describing the work of Dedekind, basing his account on Dedekind’s French article, “Sur la Théorie des Nombres entiers algébriques” (1877) Gesammelte mathematische Werke 3 pp. 262-298. Dedekind used the French word module to translate his German term Modul. Stillwell writes in the Introduction to his English translation, Theory of Algebraic Integers (1996, p. 5), “Dedekind presumably chose the name ‘module’ because a module M is something for which ‘congruence modulo M’ is meaningful.” Curiously le module had once before been translated into English but then it went into English as the MODULUS of a complex number. [John Aldrich]

MODULUS, MODULO and MOD (in number theory). Gauss introduced these terms in his Disquisitiones arithmeticae (1801, p. 9)

Si numerus a numerorum b, c differentiam metitur, b et c secundum a congrui dicuntur, sin minus, incongrui; ipsum a modulum appelamus. Uterque numerorum b, c priori in casu alterius residuum, in posteriori vero nonresiduum vocatur. [If a number a measure the difference between two numbers b and c, b and c are said to be congruent with respect to a, if not, incongruent; a is called the modulus, and each of the numbers b and c the residue of the other in the first case, the non-residue in the latter case.]

On the next page Gauss introduced the abbreviation mod. for modulo:

Numerorum congruentiam hoc signo, ≡, in posterum denotabimus, modulum ubi opus erit in clausulis adiungentes, -16 ≡ 9 (mod. 5), -7 ≡ 15 (mod. 11).

Modulus is found in English in 1811 in An Elementary Investigation of the Theory of Numbers by Peter Barlow [James A. Landau].

mod and mod. are found in 1839 in The Mathematical Miscellany Vol. II by C. Gill. [Google print search by James A. Landau]

The OED2 shows a use of mod. in English in 1854 in Cambr. & Dublin Math. Jrnl. IX. 85 and a use of mod in 1860 in Rep. Brit. Assoc. Adv. Sci. 1859.

Modulo appears in English in 1887 in American Journal of Math. vol. 10, p. 62 [Mark Dunn, JSTOR].

Modulo (non-technical sense). Modulo is being widely used by mathematicians in a related sense of "(a) taking into account (a particular consideration, aspect, etc.) (b) with respect to an equivalence defined by (some feature)." [This is the definition which will be given by the OED, according to Mark Dunn.]

In the spring of 1953, in a letter to Paul Halmos, Warren Ambrose of Princeton wrote: "[Nash] proceeded to announce that he had solved it, modulo details, and told Mackey he would like to talk about it at the Harvard colloquium." In this citation, modulo means "except for" or "without." This letter, which was critical of John Nash’s attempt (later successful) to prove the Riemann Imbedding Theorem, is quoted in A Beautiful Mind by Sylvia Nasar [James A. Landau]

Carlos César de Araújo provides these examples:

MODULUS (in logarithms) was used by Roger Cotes (1682-1716) in 1722 in Harmonia Mensurarum: Pro diversa magnitudine quantitatis assumptae M, quae adeo vocetur systematis Modulus. Cotes also coined the term ratio modularis (modular ratio) in this work.

Modulus is found in English in 1806 in A Treatise on Plane and Spherical Trigonometry: With Their Most Useful Practical Applications by John Bonnycastle: "Where M = 1 for hyperbolic logarithms, or = 2.802585093 for the common tabular logarithms; which number is the hyperbolic logarithm of 10, what is usually called the modulus of the system." [Google print search]

MODULUS (a coefficient that expresses the degree to which a body possesses a particular property) appears in the 1738 edition of The Doctrine of Chances: or, a Method of Calculating the Probability of Events in Play by Abraham De Moivre (1667-1754) [James A. Landau].

MODULUS (in the Theory of Errors). In his first theory of least squares based on the normal distribution and presented in Gauss’s Theoria Motus Corporum Coelestium in Sectionibus Conicis Solem Ambientum (1809) Gauss used a measure of precision ("mensura praecisionis observationum" (p. 245) which he denoted by h: the reciprocal of h is √2σ, where σ is the standard deviation. Both h and its reciprocal have been called the modulus: the reciprocal in G. B Airy’s On the Algebraical and Numerical Theory of Errors of Observation and the Combination of Observations (1861, p. 15) and h in E. T. Whittaker & G. Robinson’s Calculus of Observations (1924, p. 175). See METHOD OF LEAST SQUARES and also Symbols Associated with the Normal Distribution on the Symbols in Probability and Statistics page.

At the end of the 19th century the standard deviation began to replace the modulus in the biometric/statistical literature but writers in the error theory tradition continued to use the modulus, see e.g. Harold Jeffreys’s "An Alternative to the Rejection of Observations," Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, 137, (1932), pp. 78-87. The term now seems to have dropped out of use completely. See STANDARD DEVIATION.

MODULUS. The term modulus ("le module") for the length of the vector a + bi is due to Jean Robert Argand (1768-1822) (Cajori 1919, page 265). According to William F. White in A Scrap-Book of Elementary Mathematics (1908), the term was first used by him in his 1814 Reflexions. The passage is on p. 122 of the edition of Essai sur une manière de représenter les quantités imaginaires dans les constructions géométriques.

The term was adopted by Cauchy and chapter VII of his

Cours

d'Analyse (1821, p. 173ff.) has the title Des expressions imaginaires et de leurs

modules. The OED’s earliest English quotation is from 1866 W. T. Brande & G. W. Cox

A dictionary of science, literature and

art II. 551/2 "The positive

square root of a2 + b2 is often termed the modulus

of the imaginary expression  ."

Because modulus had other meanings German writers preferred the term Der absolute Betrag (= ABSOLUTE VALUE).

[John Aldrich]

."

Because modulus had other meanings German writers preferred the term Der absolute Betrag (= ABSOLUTE VALUE).

[John Aldrich]

MODULUS (the quantity c in the formula ∫ 1 / √ (1 – c2 sin2 φ) dφ) appears in French (same spelling as in English) in Legendre’s 1792 paper Mémoire Sur Les Transcendantes Elliptiques. “Modulus” appeared in English in 1809 in the translation of this paper in Thomas Leybourn, ed The Mathematical Repository, New Series, Volume III (1809). [James A. Landau]

The term MODULUS OF TRANSFORMATION was used in 1882 by George M. Minchin in Uniplanar Kinematics of Solids and Fluids: "It will be convenient to speak of this quantity K as a modulus of transformation" [OED].

MOMENT was used in the obsolete sense of "an infinitesimal increment or decrement of a varying quantity" by Isaac Newton in 1704 in De Quadratura Curvarum: "Momenta id est incrementa momentanea synchrona" [OED].

Moment appears in English in the obsolete sense of "momentum" in 1706 in Synopsis Palmariorum Matheseos by William Jones: "Moment..is compounded of Velocity..and..Weight" [OED].

Moment of a force appears in 1830 in A Treatise on Mechanics by Henry Kater and Dionysius Lardner [OED].

Moment was taken into Statistics from Mechanics by Karl Pearson when he treated the frequency-curve (or observation curve) as the sheet enclosed by the curve and the horizontal axis. See his "Asymmetrical Frequency Curves," Nature October 26th 1893: "Now the centre of gravity of the observation curve is found at once, also its area and its first four moments by easy calculation." [OED].

The phrase method of moments was used in a statistics sense in the first of Karl Pearson’s "Contributions to the Mathematical Theory of Evolution," (Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 185, (1894), p. 75.). Pearson used the method to estimate the parameters of a mixture of normal distributions. For several years Pearson used the method on different problems but the name only gained general currency with the publication of his 1902 Biometrika paper "On the systematic fitting of curves to observations and measurements" (David 1995). In "On the Mathematical Foundations of Theoretical Statistics" (Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 1922), Fisher criticized the method for being inefficient compared to his own maximum likelihood method (Hald pp. 650 and 719).

Moment generating function. R. A. Fisher seems to have brought this term into English in his "Moments and Product Moments of Sampling Distributions.," Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Series 2, 30, (1929), p. 238. He probably took the term from V. Romanovsky "Sur Certaines Éspérances Mathématiques et sur l'Erreur Moyenenne du Coefficient de Corrélation, Comptes Rendus, 180, (1925), 1897-1899. Romanovsky refers to "la function génératrice des moments" (p. 1898).

Some English publications of the 1930s, including M. S. Bartlett’s "On the Theory of Statistical Regression," Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 53, (1933), 260-283, used the term for what is now called the characteristic function. The modern division of labour between the two terms seems to have been fixed from around 1940.

This entry was contributed by John Aldrich. See CHARACTERISTIC FUNCTION (1).

The term MONOGENIC (for a function having a single derivative at a point) was introduced by Augustin-Louis Cauchy (1789-1857).

The earliest appearance of this word in Google Books is in 1872 in a mathematics examination.

MONOMIAL appears in English in 1702 in A Mathematical Dictionary: Or; A Compendious Explication of All Mathematical Terms by Joseph Raphson and Jacques Ozanam: "Monomial, is a Magnitude of one Name, or one only Term, as ab, aab, aaab, &c." [Google print search]

MONOMORPHISM appears in S. Eilenberg and S. MacLane “On the Groups H(Π, n), II: Methods of Computation,” Annals of Mathematics, Second Series, 60, (1954), p. 83: “A monomorphism f : A → B is a homomorphism with kernel zero; an epimorphism f : A → B is a homomorphism with f(A) = B. Thus “epimorphism” means “homomorphism onto”, while “isomorphism” is reserved for its proper meaning, “isomorphism onto.” (OED)

MONOTONE, MONOTONIC, and MONOTONOUS have all been used as translations of the German monoton. Before it acquired a mathematical meaning monoton was used of a voice that is uninflected or monotonous.

The Century Dictionary (1890) has the definition, “Monotonous function, a function whose value within certain limits of the real variable continually increases or continually decreases.” The German word monoton appears (in italics) in W. F. Osgood’s “The Law of the Mean and the Limits ∞/∞,” Annals of Mathematics, 12, (1898–1899), 73. Osgood used monotonic (without italics) in “Sufficient Conditions in the Calculus of Variations,” Annals of Mathematics, 2, (1900-1901), p. 116 and monotone (without italics) appears in E. B. Van Vleck “On an Extension of the 1894 Memoir of Stieltjes,” Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 4, (1903), p. 311. These words flourished and monotonous is now rare in mathematics. [John Aldrich]

MONTE CARLO with reference to the use of (pseudo) RANDOM NUMBERS for solving numerical problems. In his autobiography Adventures of a Mathematician Stanislaw M. Ulam (1976, pp. 196-200) wrote that such a method came to him while playing solitaire during an illness in 1946. Ulam described the method to John von Neumann and they “developed the mathematics together.” In an unpublished manuscript, “The Origin of the Monte Carlo Method,” dated Apr. 12, 1983, Ulam adds that what seems to be the first written account of the method was given by von Neumann in a letter to Robert Richtmyer of Los Alamos in early 1947.

The first publication to describe the method was “The Monte Carlo Method” by Ulam and Metropolis in the Journal of the American Statistical Association, 44, (1949), 335-341. A news item in Math. Tables & Other Aids to Computation III, (1949), p. 546 reports a Symposium on Probability Methods in Numerical Analysis at which both Ulam and von Neumann spoke. The Monte Carlo method and its history are explained as follows: “This method of solution of problems in mathematical physics by sampling techniques based on random walk models constitutes what is known as the ‘Monte Carlo’ method. The method as well as the name for it were apparently first suggested by John von Neumann and S. M. Ulam.” However, in his article “The Beginnings of the Monte Carlo Method” Los Alamos Science Special Issue 1987 here Metropolis recalls that he suggested the name, “a suggestion not unrelated to the fact that Stan had an uncle who would borrow money from relatives because he ‘just had to go to Monte Carlo.’”

Ulam and von Neumann exploited the random number generation possibilities of the new electronic COMPUTER to solve differential equations and their Monte Carlo method would now be classified as a form of MARKOV CHAIN MONTE CARLO. Computer-based sampling techniques were soon applied to other problems, particularly those arising in statistical distribution theory, and the term Monte Carlo was used for these applications as well. These exercises resembled the “experimental sampling” of the pre-electronic computer age, examples of which can be found in the famous 1908 paper by Student (see STUDENT’S t-DISTRIBUTION) and the 1926 paper “Why Do We Sometimes Get Nonsense Correlations between Time-series? A Study in Sampling and the Nature of Time-series” by Yule (see SPURIOUS CORRELATION). It was for applications like these that the first tables of RANDOM NUMBERS were produced in 1927. See D. Teichroew (1965) A History of Distribution Sampling Prior to the Era of the Computer and its Relevance to Simulation, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 60, 27-49 and also S. M. Stigler (1991) Stochastic Simulation in the Nineteenth Century, Statistical Science, 6, 89-97 here.

This entry was contributed by John Aldrich. See also SIMULATION.

The term MONTY HALL PROBLEM appears in the second of two 1975 letters to the American Statistician written by Steve Selvin. According to the Wikipedia article on this topic, this appears to be the first use of the term. The problem, which appears in several guises, goes back a long way. It seems to have been first propounded by Joseph Bertrand in 1889. See BERTRAND’S PARADOX.

MOORE-PENROSE INVERSE. See GENERALIZED INVERSE