The plus symbol as an abbreviation for the Latin et, though appearing with the downward stroke not quite vertical, was found in a manuscript dated 1417 (Cajori).

The + and - symbols first appeared in print in Mercantile Arithmetic or Behende und hüpsche Rechenung auff allen Kauffmanschafft, by Johannes Widmann (born c. 1460), published in Leipzig in 1489. However, they referred not to addition or subtraction or to positive or negative numbers, but to surpluses and deficits in business problems (Cajori vol. 1, page 128).

Here is an image of the first use in print of the + and - signs, from Widman's Behennde vnd hüpsche Rechnung. This image is taken from the Augsburg edition of 1526.

Widman wrote, "Was - ist / das ist minus ... vnd das + das ist mer." He also wrote, "4 centner + 5 pfund" and "5 centner — 17 pfund," thus showing the excess or deficiency in the weight of boxes or bales (Smith vol. 2, page 399).

Smith (vol. 2, page 398) explains the origin of the + sign by connecting it to the Latin word for "and":

In a manuscript of 1456, written in Germany, the word et is used for addition and is generally written so that it closely resembles the symbol +. The et is also found in many other manuscripts, as in "5 et 7" for 5 + 7, written in the same contracted form, as when we write the ligature & rapidly. There seems, therefore, little doubt that this sign is merely a ligature for et.

Cajori says, "There is clear evidence that, as a lecturer at the University of Leipzig, Widmann had studied manuscripts in the Dresden library in which + and - signify operations, some of these having been written as early as 1486." Johnson (page 144) says a series of notes from 1481, annotated by Widmann, contain the + and - symbols, and he asks whether Widman could have copied these symbols from some unknown professor at the University of Leipzig. Johnson also says that a student's notes from one of Widmann's 1486 lectures show the + and - signs.

Giel Vander Hoecke used + and - as symbols of operation in Een sonderlinghe boeck in dye edel conste Arithmetica, published at Antwerp in 1514 (Smith 1958, page 341). Burton (page 335) says Vander Hoecke was the first person to use + and - in writing algebraic expressions, but Smith (page 341) says he followed Grammateus.

Henricus Grammateus (also known as Henricus Scriptor and Heinrich Schreyber or Schreiber) published an arithmetic and algebra, entitled Ayn new Kunstlich Buech, printed in 1518, in which he used + and - in a technical sense for addition and subtraction (Cajori vol. 1, page 131).

The plus and minus symbols only came into general use in England after they were used by Robert Recorde in in 1557 in The Whetstone of Witte. Recorde wrote, "There be other 2 signes in often use of which the first is made thus + and betokeneth more: the other is thus made - and betokeneth lesse."

The plus and minus symbols were in use before they appeared in print. For example, they were painted on barrels to indicate whether or not the barrels were full. Some have attempted to trace the minus symbol as far back as Heron and Diophantus.

X actually appears earlier, in 1618 in an anonymous appendix to Edward Wright's translation of John Napier's Descriptio (Cajori vol. 1, page 197). However, this appendix is believed to have been written by Oughtred.

The dot (·) was advocated by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716). According to Cajori (vol. 1, page 267):

The dot was introduced as a symbol for multiplication by G. W. Leibniz. On July 29, 1698, he wrote in a letter to John Bernoulli: "I do not like X as a symbol for multiplication, as it is easily confounded with x; ... often I simply relate two quantities by an interposed dot and indicate multiplication by ZC · LM. Hence, in designating ratio I use not one point but two points, which I use at the same time for division."Cajori shows the symbol as a raised dot. However, according to Margherita Barile, consulting Gerhardt's edition of Leibniz's Mathematische Schriften (G. Olms, 1971), the dot is never raised, but is located at the bottom of the line. She writes that the non-raised dot as a symbol for multiplication appears in all the letters of 1698, and earlier, and, according to the same edition, it already appears in a letter by Johann Bernoulli to Leibniz dated September, 2nd 1694 (see vol. III, part 1, page 148).

The dot was used earlier by Thomas Harriot (1560-1621) in Analyticae Praxis ad Aequationes Algebraicas Resolvendas, which was published posthumously in 1631, and by Thomas Gibson in 1655 in Syntaxis mathematica. However Cajori says, "it is doubtful whether Harriot or Gibson meant these dots for multiplication. They are introduced without explanation. It is much more probable that these dots, which were placed after numerical coefficients, are survivals of the dots habitually used in old manuscripts and in early printed books to separate or mark off numbers appearing in the running text" (Cajori vol. 1, page 268).

However, Scott (page 128) writes that Harriot was "in the habit of using the dot to denote multiplication." And Eves (page 231) writes, "Although Harriot on occasion used the dot for multiplication, this symbol was not prominently used until Leibniz adopted it."

The asterisk (*) was used by Johann Rahn (1622-1676) in 1659 in Teutsche Algebra (Cajori vol. 1, page 211).

By juxtaposition. In a manuscript found buried in the earth near the village of Bakhshali, India, and dating to the eighth, ninth, or tenth century, multiplication is normally indicated by placing numbers side-by-side (Cajori vol. 1, page 78).

Multiplication by juxtaposition is also indicated in "some fifteenth-century manuscripts" (Cajori vol. 1, page 250). Juxtaposition was used by al-Qalasadi in the fifteenth century (Cajori vol. 1, page 230).

According to Lucas, Michael Stifel (1487 or 1486 - 1567) first showed multiplication by juxtaposition in 1544 in Arithmetica integra.

In 1553, Michael Stifel brought out a revised edition of Rudolff's Coss, in which he showed multiplication by juxtaposition and repeating a letter to designate powers (Cajori vol. 1, pages 145-147).

The colon (:) was used in 1633 in a text entitled Johnson Arithmetik; In two Bookes (2nd ed.: London, 1633). However Johnson only used the symbol to indicate fractions (for example three-fourths was written 3:4); he did not use the symbol for division "dissociated from the idea of a fraction" (Cajori vol. 1, page 276).

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) used : for both ratio and division in 1684 in the Acta eruditorum (Cajori vol. 1, page 295).

The obelus (÷) was first used as a division symbol by Johann Rahn (or Rhonius) (1622-1676) in 1659 in Teutsche Algebra (Cajori vol. 2, page 211).

Here is the page in which the division symbol first appears in print, as reproduced in Cajori.

Rahn's book was translated into English and published, with additions by John Pell, in London in 1668, with the division symbol retained. According to some recent sources, John Pell was a major influence on Rahn and he may in fact be responsible for the invention of the symbol. However, according to Cajori there is no evidence to support this claim. The division symbol was used by many writers before Rahn as a minus sign.

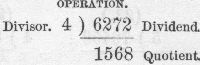

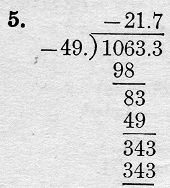

Recent symbolism. In nineteenth century U. S. textbooks, long division is typically shown with the divisor, dividend, and quotient on the same line, separated by parentheses, as 36)116(3. See the figure below.

This same 1772 book shows a vinculum above the dividend when dividing decimals:

In 1882 in Complete Graded Arithmetic by James B. Thomson, the 36)116(3 notation is used for long division. However, in examples for short division, a vinculum is placed under the dividend and the vinculum is almost attached to the bottom of the close parenthesis. The quotient is written under the vinculum, as shown below.

In 1888 in the teacher's edition of The Elements of Algebra by G. A. Wentworth the vinculum is almost attached to the top of the close parenthesis and the quotient is written above the vinculum, as shown below.

The symbolism shown above may also appear in the earlier 1882 edition of Wentworth, which has not been seen. I welcome earlier uses of this symbol that may be found by readers of this page.

In 1901, the second edition of Robinson's Complete Arithmetic by Daniel W. Fish uses the same notations for short and long division as Thomson (1882) above, except that the vinculum under the dividend is actually attached to the close parenthesis. This notation may appar in the earlier 1873 edition, which has not been seen.

David E. Smith writes, "It is impossible to fix an exact date for the origin of our present arrangement of figures in long division, partly because it developed gradually" (Smith vol. 2).

The symbol  is not mentioned by Cajori. The symbol does not have

a name.

is not mentioned by Cajori. The symbol does not have

a name.

Nicolas Chuquet (1445?-1500?) used raised numbers in Le Triparty en la Science des Nombres in 1484. However, in Chuquet's notation, 123 actually meant 12x3 (Cajori vol. 1, page 102).

In 1634, Pierre Hérigone (or Herigonus) (1580-1643) wrote a, a2, a3, etc., in Cursus mathematicus, which was published in several volumes from 1634 to 1637; the numerals were not raised, however (Cajori vol. 1, page 202, and Ball).

In 1636 James Hume used Roman numerals as exponents in L'Algèbre de Viète d'vne methode novelle, claire, et Facile. Cajori writes (vol. 1, pages 345-346):

In 1636 James Hume brought out an edition of the algebra of Vieta, in which he introduced a superior notation, writing down the base and elevating the exponent to a position above the regular line and a little to the right. The exponent was expressed in Roman numerals. Thus, he wrote Aiii for A3. Except for the use of Roman numerals, one has here our modern notation. Thus, this Scotsman, residing in Paris, had almost hit upon the exponential symbolism which has become universal through the writings of Descartes.In 1637 exponents in the modern notation (although with positive integers only) were used by Rene Descartes (1596-1650) in Geometrie. Descartes tended not to use 2 as an exponent, however, usually writing aa rather than a2, perhaps because aa occupies no less space than a2.

Descartes wrote: "aa ou a2 pour multiplier à par soiméme; et a3 pour le multiplier encore une fois par a, et ainsi à l'infini" (Cajori 1919, page 178).

Negative integers as exponents were used by Nicolas Chuquet

(1445?-1500?) in 1484 in Le Triparty en la Science des

Nombres. Chuquet wrote  to indicate 12x-1 (Cajori vol. 1, page 102).

to indicate 12x-1 (Cajori vol. 1, page 102).

Negative integers as exponents were first used with the modern notation by Isaac Newton in June 1676 in a letter to Henry Oldenburg, secretary of the Royal Society, in which he described his discovery of the general binomial theorem twelve years earlier (Cajori 1919, page 178).

Before Newton, John Wallis suggested the use of negative exponents but did not actually use them (Cajori vol. 1, page 216).

Fractions as exponents. The first use of fractional

exponents (although not with the modern notation) is by Nicole Oresme

(c. 1323-1382) in Algorismus proportionum. Oresme used  to represent 91/3.

According to Cajori (1919), this notation remained unnoticed.

to represent 91/3.

According to Cajori (1919), this notation remained unnoticed.

Simon Stevin (1548-1620) "had no occasion to use the fractional index notation," but "he clearly stated that 1/2 in a circle would mean square root and 3/2 in a circle would indicate the square root of the cube" (Boyer, page 356).

John Wallis (1616-1703), in his Arithmetica infinitorum which was published in 1656, speaks of fractional "indices" but does not actually write them (Cajori vol. 1, page 354).

Fractional exponents in the modern notation were first used by Isaac Newton in the 1676 letter referred to above (Cajori 1919, page 178).

Scientific notation. The earliest use of scientific notation is not known. However, some physicists working with electricity in in the decade or so up to 1873, when our modern volt, ohm, etc., were standardized, used scientific notation. James A. Landau has found only two usages of scientific notation in Maxwell's collected papers, and could find no other physicists of mid-century using scientific notation.

In 1863, in The Annual Encyclopedia and Register of Important Events of the Year 1862 the article on "Electricity" has on page 404:

The aim should be to make this standard [of electrical resistance] correspond to a current force equal to 10,000,000,000 times the value given by the quotient of 1 metre by 1 second of time, that is, 1010 mètre/seconds.In 1868 Rep. Brit. Assoc. 1867 has: 105 EMF, acting on a circuit of 1013, will pass in one second 10-8 absolute units of quantity; and similarly, 105 EMF will charge a condenser of absolute capacity equal to 10-13 absolute units with 10-8 absolute units of quantity... Mr. Clark calls the unit of quantity thus defined (10-8) one Farad, and similarly says that the unit of capacity has a capacity of one Farad, it being understood that this is the capacity when charged with unit electromotive force (105).

The above quotation was taken from the OED2.

In 1885 Johann Jakob Balmer in "Notiz uber die Spectrallinien des Wasserstoffs" (Annalen der Physik and Chemie, Vol. 25, p. 80, 1885) wrote in English translation:

From the formula we obtained for a fifth hydrogen line49/45 · 3645.6 = 3969.65 · 10-7 mm

In 1887 Albert Abraham Michelson and Edward Williams Morley wrote in Philosophical Magazine, Series 5, December, 1887:

Considering the motion of the earth in its orbit only, this displacement should beBoth of these citations were taken from A Source Book in Physics by William Francis Magie.2 D v2/V2 = 2D x 10-8The distance D was about eleven metres, or 2 x 107 wave-lengths of yellow light.

An even earlier possible use of scientific notation is by Robert Whillhelm Bunsen in 1857 in Philosophical Transactions, where these formulae appear on page 357:

I = I0 10-hαHowever the objection is that Bunsen was measuring the intensity of light before and after going through a tube of chlorine, and the alpha above is defined as "The value of 1/alpha, which signifies...the depth of chlorine to which the chemical rays must penetrate in order to be reduced to one-tenth of their original amount..." Therefore the 10 is not necessarily part of scientific notation but comes from the fact that Bunsen elected to measure a reduction of light to one-tenth of the original.I = I1 10-hα + I2 10-hα + ...

This entry was largely contributed by James A. Landau.

In 1892 in Mental Arithmetic, M. A. Bailey advises avoiding expressions containing both ÷ and ×.

In 1898 in Text-Book of Algebra by G. E. Fisher and I. J. Schwatt, a÷b×b is interpreted as (a÷b)×b.

In 1907 in High School Algebra, Elementary Course by Slaught and Lennes, it is recommended that multiplications in any order be performed first, then divisions as they occur from left to right.

In 1910 in First Course of Algebra by Hawkes, Luby, and Touton, the authors write that ÷ and × should be taken in the order in which they occur.

In 1912, First Year Algebra by Webster Wells and Walter W. Hart has: "Indicated operations are to be performed in the following order: first, all multiplications and divisions in their order from left to right; then all additions and subtractions from left to right."

In 1913, Second Course in Algebra by Webster Wells and Walter W. Hart has: "Order of operations. In a sequence of the fundamental operations on numbers, it is agreed that operations under radical signs or within symbols of grouping shall be performed before all others; that, otherwise, all multiplications and divisions shall be performed first, proceeding from left to right, and afterwards all additions and subtractions, proceeding again from left to right."

In 1917, "The Report of the Committee on the Teaching of Arithmetic in Public Schools," Mathematical Gazette 8, p. 238, recommended the use of brackets to avoid ambiguity in such cases.

In A History of Mathematical Notations (1928-1929) Florian Cajori writes (vol. 1, page 274), "If an arithmetical or algebraical term contains ÷ and ×, there is at present no agreement as to which sign shall be used first."

Modern textbooks seem to agree that all multiplications and divisions should be performed in order from left to right. However, in Florida Algebra I published by Prentice Hall (2011), a problem asks the student to evaluate 3st2 ÷ st + 6 for given values of the variables, and the answer provided comes from dividing by st. A representative for the publisher has acknowledged that the expression is ambiguous and promises to use (st) in the next revision.

X for vector product was used in 1902 in J. W. Gibbs's Vector Analysis by E. B. Wilson.

Plus-or-minus symbol (±) was used by William Oughtred (1574-1660) in Clavis Mathematicae, published in 1631 (Cajori vol. 1, page 245).

Postfix notation or RPN began as prefix notation, a mathematical notation which did away with grouping symbols. It was proposed by Jan Lukasiewicz (1878-1956). "Prefix" meant that the operators ( * + - etc.) preceded the operands or variables they were meant to operate on. Then it was discovered that it is much more convenient to place the operands first and operators last, so "Postfix" or "reverse Lukasiewicz" or "reverse Polish" notation was created. With postfix notation the operators themselves become delimiters between operations. Thus the sequence U*(V^(W + 3))/(X - Y) becomes

RPN is used in the computer language Forth. [Axel Harvey]

The product symbol ( ) was introduced by Rene Descartes, according to Gullberg.

) was introduced by Rene Descartes, according to Gullberg.

Cajori says this symbol was introduced by Gauss in 1812 (vol. 2, page 78).

Square root. The first use of  was in 1220 by Leonardo of Pisa in

Practica geometriae, where the symbol meant "square root"

(Cajori vol. 1, page 90).

was in 1220 by Leonardo of Pisa in

Practica geometriae, where the symbol meant "square root"

(Cajori vol. 1, page 90).

The radical symbol first appeared in 1525 in Die Coss by

Christoff Rudolff (1499-1545). He used  (without the vinculum) for square roots. He did not use

indices to indicate higher roots, but instead modified the appearance

of the radical symbol for higher roots.

(without the vinculum) for square roots. He did not use

indices to indicate higher roots, but instead modified the appearance

of the radical symbol for higher roots.

It is often suggested that the origin of the modern radical symbol is that it is an altered letter r, the first letter in the word radix. This is the opinion of Leonhard Euler in his Institutiones calculi differentialis (1775). However, Florian Cajori, author of A History of Mathematical Notations, argues against this theory.

In 1637 Rene Descartes used  , adding the

vinculum to the radical symbol La Geometrie (Cajori vol. 1,

page 375).

, adding the

vinculum to the radical symbol La Geometrie (Cajori vol. 1,

page 375).

Placement of the index within the opening of the radical sign was suggested in 1629 by Albert Girard (1595-1632) in Invention nouvelle. He suggested this notation for the cube root (DSB; Cajori vol. 1, page 371).

According to Cajori (vol. 1, page 372) the first person to adopt Girard's suggestion and place the index within the opening of the radical sign was Michel Rolle (1652-1719) in 1690 in Traité d'Algèbre.

However, a history note in a high school textbook states that the symbol was first used by Girard “around 1633” (UCSMP Advanced Algebra, 2nd ed., 1996, page 496).

According to Tropfke, Geschichte der Elementarmathematik, 4th edition, vol. 1: Arithmetik und Algebra, Berlin/New York: De Gruyter, 1980, p. 296, Girard introduced this use with examples for the cubic and the quintic root on fol. 1r° of the Invention nouvelle and suggested on the same page also (3/2)49 for the fractional exponent of 49 [3/2 written as fraction]. [This information contributed by Siegmund Probst.]

Examples of Leibniz's use of the radical sign with index placed in the opening:

VII,3 N. 57_2 p. 736 (End of April 1676)

VII,3 N. 58 p. 752 (May 3, 1676)

VII,3 N. 60 p. 760 (June 26, 1676)

See http://www.nlb-hannover.de/Leibniz/Leibnizarchiv/Veroeffentlichungen/VII3C.pdf.

In the Mathematical Gazette of Feb. 1895, G. Heppel wrote, "Following Chrystal, Todhunter, Hall and Knight, and the majority of writers [sqrt]a should be considered a quantity having one and not two values, although the algebra of C. Smith and the article by Professor Kelland in the Encyclopedia Britannica make [sqrt]a have two values."

Summation. The summation symbol Σ was first used by Leonhard Euler (1707-1783) in 1755:

Quemadmodum ad differentiam denotandam vsi sumus signo Δ, ita summam indicabimus signo Σ.The citation above is from Institutiones calculi differentialis (St. Petersburg, 1755), Cap. I, para. 26, p. 23. The original Latin can be seen here.

Part of E212 (Eneström number) has been translated by John Blanton, as Euler. Foundations of Differential Calculus (Springer). The relevant sentence is on page 17 of Blanton. His translation is:

Just as we used the symbol Δ to signify a difference, so we use the symbol Σ to indicate a sum.

This symbol was used by Lagrange, but otherwise received little attention during the eighteenth century (Cajori vol. 2, pages 61 and 265.)

[Some information contributed by V. Frederick Rickey.]

Absolute value of a difference. The tilde was introduced for this purpose by William Oughtred (1574-1660) in the Clavis Mathematicae (Key to Mathematics), composed about 1628 and published in London in 1631, according to Smith, who shows a reversed tilde (Smith 1958, page 394).

Matrices. In 1841, Arthur Cayley (1821-1895) used the modern notation for the determinant of a matrix, a single vertical line on both sides of the entries. The notation appeared in the Cambridge Mathematical Journal, Vol. II (1841), p. 267-271. However, Cayley used commas to separate entries within rows (Cajori vol. 2, page 92).

The double vertical line notation was introduced by Cayley in 1843 (Cajori vol. 2, page 95).

In 1846, the first occurrence of both the single vertical line notation for determinants and double vertical lines for matrices is found in "Mémoire sur les hyperdéterminants" by Arthur Cayley in Crelle's Journal (Cajori vol. 2, page 93).

Cajori (vol. 2, p. 103) writes that round parentheses were used for matrices by many, including Maxine Bocher in 1919 in Introduction to Higher Algebra and G. Kowalewski in 1909 in Determinantentheorie (although Kowalewski also used double vertical lines and a single brace).

Cajori also shows a use of brackets for matrices (and no commas within) by C. E. Cullis in Matrices and Determinoids in 1913.

Arrow notation. In 1936 in L'Agebre Abstraite Oystein Ore wrote:

Nous dirons que deux systemes algebriques S et S' sont homomorphes (par rapport a l'addition et a la multiplication) s'il existe une correspondance a —> a' entre les elements de S et S' donnant a chaque element a de S une image unique a' dans S' telle que chaque element de S' soit l'image d'au moins un element de S et en outre telle que de a —> a', b --> b' on puisse conclure

As early as 1939 Bourbaki used the arrow in element-to-element notation ["la application x —> f(x)"].

Saunders Mac Lane wrote:

At first the vivid arrow notation f : X —> Y for a map was not available, and homomorphisms of homology groups (or rings) were always expressed in terms of the corresponding quotient group or rings. Thus the familiar long exact sequence of the homotopy groups of a fibration was originally described in terms of subgroups and quotient groups; this is the style used by all three discoveries of the sequence and of the covering homotopy theorem [...] The occurrence of exact sequences of homology groups (though not the name 'exact') was first noted by W. Hurewicz in 1941 [...] The practice of using an arrow to represent a map f : X —> Y arose at the same time. I have not been able to determine who first introduced this convenient notation; it may well have appeared first on the blackboard, perhaps in lectures by Hurewicz and it is used in the Hurewicz-Steenrod paper, submitted November 1940 ...The above quotation is from Saunders Mac Lane, "Concepts and Categories in Perspective," A Century of Mathematics in America, Part I, AMS, vol 1, 1988 [Julio González Cabillón].